A Large, Candid Group of Letters Documenting Marital Infidelity, Love, Divorce and Unemployment in Depression-Era Northern California

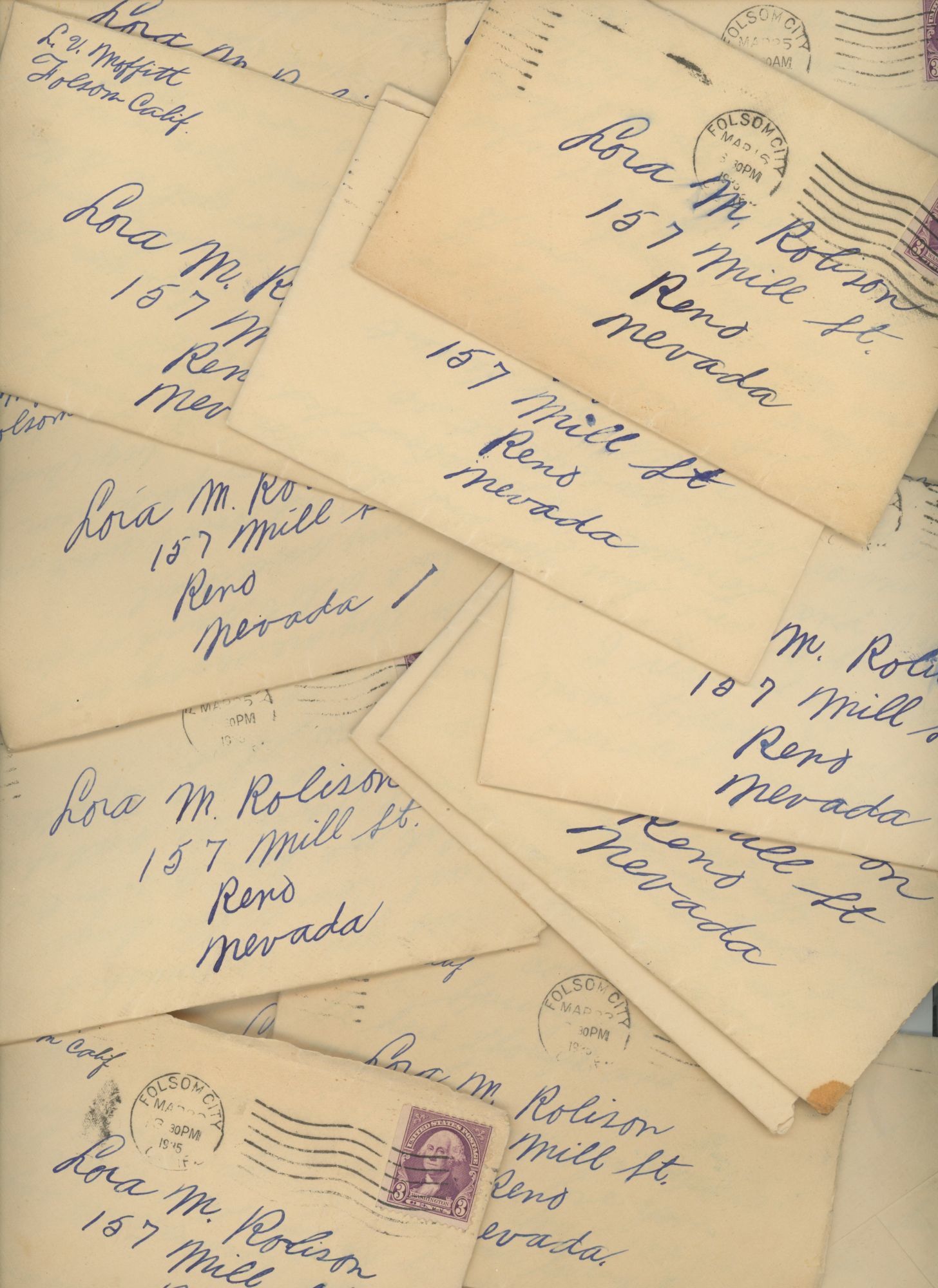

- Approx. 226 letters with 10 empty envelopes: , Mainly Between Leland Victor Moffitt (1904–1994) and Lora Marie Rolison, née H

- California , 1935

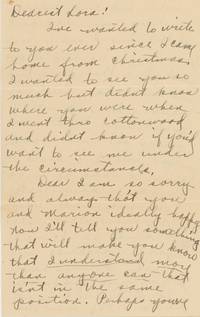

California, 1935. Approx. 226 letters with 10 empty envelopes: , Mainly Between Leland Victor Moffitt (1904–1994) and Lora Marie Rolison, née Hickman (1897–1984).appx 102 letters to Leland from Lora; 94 letters to Lora from Leland; 30 letters from friends and family. Lora Rolison and Leland Moffitt probably met at Lora’s family’s ranch in Cottonwood, Shasta County, where she lived with her husband Marion Rolison (1896–1949), their son Money Rolison (1922–????), and likely some other members of Lora’s family. It’s unclear exactly how or when the affair began, although Leland seems to have been sent away to Folsom, just outside of Sacramento, in October of 1934 – probably because the affair was discovered. Lora says of her husband Marion that:

“When I say Lee did this or that, he nearly goes wild [...] He took me to town [...] yesterday and was dreadful very nice until I said how much I missed you then the excitement started. Well its no worse to say it than think [it]. (October 16, 1934)”

Marion takes the infidelity hard. Lora tells Leland that:

“[...] the hard part is to have him keep asking me if I love him or if I ever will again – he said last evening even if I didnt love him he’d always love me. (October 27th, 1934)”

Thus begins a correspondence, mostly carried out in secret, between the lovers – more than 200 letters over the course of seven months, from October 1934 to April 1935, when Lora finalizes her divorce from Marion and she and Leland are reunited for good.

Lora and Leland are clearly from different economic strata, a difference made all the more striking by the conditions of the Great Depression. Lora formulates a plan to travel to Reno and establish residency so that she can pay $140 for her divorce from Marion, from which she will receive a settlement of about $650 (about $3,000 and $15,000 today, respectively). She often tells Leland about her new clothes and hairstyles. Leland, meanwhile, struggles to find and keep work. In November of 1934, he finds employment on a dredge:

“I am going to work Monday or Tuesday if this rain doesn’t hold things up. It isn’t the best job in the world but I surely am glad to get it, only pays 45 cents per hour, 8 hours a day, but I may get more later. It will be a start anyway sweetheart. With good luck it will not be so long untill I can support a wife. “(November 3, 1934)

And he is overjoyed to have done so – Lora writes:

“You could just tell, sweetheart, how happy you were, that letter fairly radiated happiness, your Moms, too. Oh, Lee, dearest, was I happy too, your family + I just whooped for joy – everyone was so happy Darryl hugged Muriel + I hugged your Mom – Cause we knew how happy our sweetheart was that he had found something to do – (November 6, 1934)

But this is not to last. By December, Leland is unemployed again:

“We went down to the new boat but there was nothing doing. Material is coming in very slowly. Surely hope I get to work soon so I can have my sweetheart with me. [...] I saw Lears yesterday, he could not promise me any thing definite at this time. Said he was having a hard time keeping what men he had busy. “(December 17, 1934)

As with many men during the Depression, the lack of

work takes a psychological toll on Leland. He describes himself variously as ‘unworthy’:

“God it is hard to wait sweetheart I feel so small and useless and unworthy of you. Seems like if I were any good at all I could find something to do.” (December 19, 1934)

...a ‘bum’:

“I certainly would like to send you a nice present for Christmas, but guess I can’t right now. You have a bum sweetheart, my darling. [...] It is terrible sweetheart when a person needs a job as much as I do and can’t get one, seems like things get worse all of the time.” (December 20, 1934)

...and ‘useless’:

“It is terrible doing nothing to make the money that we need so bad. I keep hoping every day for something but nothing happens. [...] I feel so useless and disgusted with myself sometimes I don’t know what to do. I am willing to do anything that there is a living in but there doesn’t seem to be anything.” (January 18, 1935)

Leland is emasculated by the lack of work – and the humiliation keeps going, as in April of 1935 he is continually being told by superintendents and foremen that it will only be ‘a few more days’ before work will certainly start up again. Leland’s brother-in-law Frank is having a similar experience. Frank’s wife, Muriel, writes:

“That job at [...]ville fell through. After telling Frank to

keep coming back for about four months, the boss finally told him about a week ago that he couldn’t promise him anything. Said the men he had were just in each other’s way.” (April 11, 1935)

Frank tries for a job at a mine, but the mine isn’t making any money:

“Jack McGovern, a kid at the mine that we know, said that he wouldn’t be surprised if the mine shut down most any time as he didn’t think it was paying.”

And meat processing will not work out, either, because nobody is buying meat:

“Nothing doing on that meat job at Roseville. Meat has gone up so terribly high that very little of it is being sold.”

Another striking difference lies in the two’s gendered experiences. As Leland is emasculated by lack of work, Marion—whom Lora frequently refers to as ‘the Boss’—apparently reacts quite differently to his own emasculation. Discussing her divorce proceedings, Lora casually mentions to Leland that:

“Mrs Preston says they always favor the women here + I will get it [the settlement money] by default – I’ll bring in the charge of him choking me if he gets too funny.” (March 21, 1935)

But Lora has a strong support system – particularly of other women who had also gone through divorces. After seeing her lawyer for the first time in November of 1934, she mentions:

“I’m going to see Pearl, too, she probably can give me some good information having gone through the deal. “(November 12, 1934)

And Lora’s cousin follows her lead:

“Walter + I are seperating. He’s got a girl friend + got sassy + fresh to me in her presence before others + I surely told him plenty. He’s still here untill money matters are settled [...] I just can’t stand him around now, it’s unbearable. [...] I’ve suffered agonies mentally for so long taking his smartness + now that its settled + I’m making a move I feel like a different person. “(February 27, 1935)

Indeed, Lora is also unafraid to stand up to her abusive husband. She tells Leland:

“He started in to give me the [...] about going by for Muriel yesterday and I said “Now thats just about enough I’m not going to take any more – Then pretty quick he came over and kissed me + said he was sorry – “Till the next time” The other night he raved around til 3 A.M. trying to get me to promise to forget you + say I wouldn’t go see the folks – I told him I wouldn’t do any such thing.” (November 6, 1934)

As his final tactic to wear away at Lora’s resolve, Marion refuses to respond to her lawyer’s request to sign their divorce papers – while she’s living in Reno, she endures weeks of complete silence from Marion and his lawyers. Finally, on March 30, he signs the papers. Lora writes to Leland:

“Well, I guess this will be my last love letter for a while + I hope for always [...] Sweetheart, do you know that to-morrow then Saturday – Then when that choo choo train comes in Sunday – I sure hope I’ll see my sweetheart (April 11, 1935)

From the remainder of the letters, addressed to the couple from family and friends, it seems that they managed to live more or less happily ever after – both emotionally and financially, though details of the latter are not discussed. A letter from a friend sums it up well:

I certainly am pleased to hear of your good luck. I sincerely hope Lee continues to step up. You deserve all the breaks you’ll get. More power to you! (July 5, 1936)

This intimate set of letters tells a compelling story of love and perseverance during an incredibly difficult time in American history.

“When I say Lee did this or that, he nearly goes wild [...] He took me to town [...] yesterday and was dreadful very nice until I said how much I missed you then the excitement started. Well its no worse to say it than think [it]. (October 16, 1934)”

Marion takes the infidelity hard. Lora tells Leland that:

“[...] the hard part is to have him keep asking me if I love him or if I ever will again – he said last evening even if I didnt love him he’d always love me. (October 27th, 1934)”

Thus begins a correspondence, mostly carried out in secret, between the lovers – more than 200 letters over the course of seven months, from October 1934 to April 1935, when Lora finalizes her divorce from Marion and she and Leland are reunited for good.

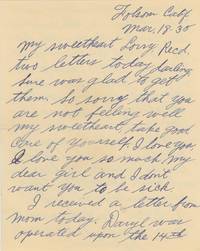

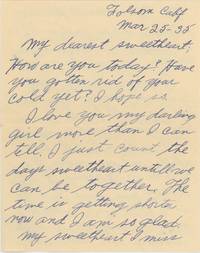

Lora and Leland are clearly from different economic strata, a difference made all the more striking by the conditions of the Great Depression. Lora formulates a plan to travel to Reno and establish residency so that she can pay $140 for her divorce from Marion, from which she will receive a settlement of about $650 (about $3,000 and $15,000 today, respectively). She often tells Leland about her new clothes and hairstyles. Leland, meanwhile, struggles to find and keep work. In November of 1934, he finds employment on a dredge:

“I am going to work Monday or Tuesday if this rain doesn’t hold things up. It isn’t the best job in the world but I surely am glad to get it, only pays 45 cents per hour, 8 hours a day, but I may get more later. It will be a start anyway sweetheart. With good luck it will not be so long untill I can support a wife. “(November 3, 1934)

And he is overjoyed to have done so – Lora writes:

“You could just tell, sweetheart, how happy you were, that letter fairly radiated happiness, your Moms, too. Oh, Lee, dearest, was I happy too, your family + I just whooped for joy – everyone was so happy Darryl hugged Muriel + I hugged your Mom – Cause we knew how happy our sweetheart was that he had found something to do – (November 6, 1934)

But this is not to last. By December, Leland is unemployed again:

“We went down to the new boat but there was nothing doing. Material is coming in very slowly. Surely hope I get to work soon so I can have my sweetheart with me. [...] I saw Lears yesterday, he could not promise me any thing definite at this time. Said he was having a hard time keeping what men he had busy. “(December 17, 1934)

As with many men during the Depression, the lack of

work takes a psychological toll on Leland. He describes himself variously as ‘unworthy’:

“God it is hard to wait sweetheart I feel so small and useless and unworthy of you. Seems like if I were any good at all I could find something to do.” (December 19, 1934)

...a ‘bum’:

“I certainly would like to send you a nice present for Christmas, but guess I can’t right now. You have a bum sweetheart, my darling. [...] It is terrible sweetheart when a person needs a job as much as I do and can’t get one, seems like things get worse all of the time.” (December 20, 1934)

...and ‘useless’:

“It is terrible doing nothing to make the money that we need so bad. I keep hoping every day for something but nothing happens. [...] I feel so useless and disgusted with myself sometimes I don’t know what to do. I am willing to do anything that there is a living in but there doesn’t seem to be anything.” (January 18, 1935)

Leland is emasculated by the lack of work – and the humiliation keeps going, as in April of 1935 he is continually being told by superintendents and foremen that it will only be ‘a few more days’ before work will certainly start up again. Leland’s brother-in-law Frank is having a similar experience. Frank’s wife, Muriel, writes:

“That job at [...]ville fell through. After telling Frank to

keep coming back for about four months, the boss finally told him about a week ago that he couldn’t promise him anything. Said the men he had were just in each other’s way.” (April 11, 1935)

Frank tries for a job at a mine, but the mine isn’t making any money:

“Jack McGovern, a kid at the mine that we know, said that he wouldn’t be surprised if the mine shut down most any time as he didn’t think it was paying.”

And meat processing will not work out, either, because nobody is buying meat:

“Nothing doing on that meat job at Roseville. Meat has gone up so terribly high that very little of it is being sold.”

Another striking difference lies in the two’s gendered experiences. As Leland is emasculated by lack of work, Marion—whom Lora frequently refers to as ‘the Boss’—apparently reacts quite differently to his own emasculation. Discussing her divorce proceedings, Lora casually mentions to Leland that:

“Mrs Preston says they always favor the women here + I will get it [the settlement money] by default – I’ll bring in the charge of him choking me if he gets too funny.” (March 21, 1935)

But Lora has a strong support system – particularly of other women who had also gone through divorces. After seeing her lawyer for the first time in November of 1934, she mentions:

“I’m going to see Pearl, too, she probably can give me some good information having gone through the deal. “(November 12, 1934)

And Lora’s cousin follows her lead:

“Walter + I are seperating. He’s got a girl friend + got sassy + fresh to me in her presence before others + I surely told him plenty. He’s still here untill money matters are settled [...] I just can’t stand him around now, it’s unbearable. [...] I’ve suffered agonies mentally for so long taking his smartness + now that its settled + I’m making a move I feel like a different person. “(February 27, 1935)

Indeed, Lora is also unafraid to stand up to her abusive husband. She tells Leland:

“He started in to give me the [...] about going by for Muriel yesterday and I said “Now thats just about enough I’m not going to take any more – Then pretty quick he came over and kissed me + said he was sorry – “Till the next time” The other night he raved around til 3 A.M. trying to get me to promise to forget you + say I wouldn’t go see the folks – I told him I wouldn’t do any such thing.” (November 6, 1934)

As his final tactic to wear away at Lora’s resolve, Marion refuses to respond to her lawyer’s request to sign their divorce papers – while she’s living in Reno, she endures weeks of complete silence from Marion and his lawyers. Finally, on March 30, he signs the papers. Lora writes to Leland:

“Well, I guess this will be my last love letter for a while + I hope for always [...] Sweetheart, do you know that to-morrow then Saturday – Then when that choo choo train comes in Sunday – I sure hope I’ll see my sweetheart (April 11, 1935)

From the remainder of the letters, addressed to the couple from family and friends, it seems that they managed to live more or less happily ever after – both emotionally and financially, though details of the latter are not discussed. A letter from a friend sums it up well:

I certainly am pleased to hear of your good luck. I sincerely hope Lee continues to step up. You deserve all the breaks you’ll get. More power to you! (July 5, 1936)

This intimate set of letters tells a compelling story of love and perseverance during an incredibly difficult time in American history.