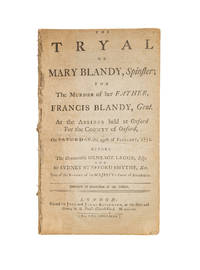

The Tryal of Mary Blandy, Spinster, For the Murder of Her Father

- 1752

1752. The "Love Philter" was Arsenic [Trial]. Blandy, Mary [1720-1752], Defendant. The Tryal of Mary Blandy, Spinster; For the Murder of Her Father, Francis Blandy, Gent. At the Assizes Held at Oxford for the County of Oxford, On Saturday the 29th of February, 1752, Before the Honourable Heneague Legge, Esq; and Sir Sydney Stafford Smythe, Knt. Two of the Barons of His Majesty's Court of Exchequer. Published by Permission of the Judges. London: Printed for John and James Rivington, At the Bible and Crown, In St. Paul's Church Yard, 1752. [ii], 46 pp. Folio (11-3/4" x 7"). Disbound stab-stitched pamphlet. Moderate toning, margins trimmed closely with no loss to text. Light soiling to exterior, clean tear from a fold near center of lower half of text block, early repairs to inner margins of several leaves, a few minor tears and chips to edges of title page, chips, a few tears with minor loss to text to final leaf. $250. * Only edition, one of three issues, the others an octavo issued by Rivington and an octavo issued in Dublin by Faulkner. Blandy was the daughter of a prosperous lawyer. Her father, Francis, advertised a large dowry of ?10,000, which attracted many suitors, including one who captivated her, Captain William Henry Cranstoun, the son of a Scottish nobleman. Francis learned later that he was married and a father. Confronted with these facts by Francis, Cranstoun claimed his marriage was invalid and made several attempts, he claimed, to have it annulled. Over time Francis became suspicious about Cranstoun's motives. Sensing danger, Cranstoun gave Mary a "love philtre" and told her to mix it into one of her father's meals. He said it would change his behavior towards him. It was actually arsenic. When Mary realized what she had done, she foolishly burned Cranstoun's letters and discarded the rest of the arsenic. Cranstoun fled to France. Mary was tried and sentenced to death by hanging. This was a sensational trial and it was covered extensively by the press. It also generated a secondary literature that included several contributions written by Mary, such as "Miss Mary Blandy's Own Account of the Affair between Her and Mr. Cranstoun." As indicated by her last request to the execution officials, she remained a proper middle-class lady to the end. "For the sake of decency, gentlemen," she pleaded, "don't hang.