Original Archive of Childhood and Mature Art by Gladys Mary Black (1895-1979) and Siblings of Torquay, Devon, 1910-1968

- Torquay, Devon, United Kingdom , 1968

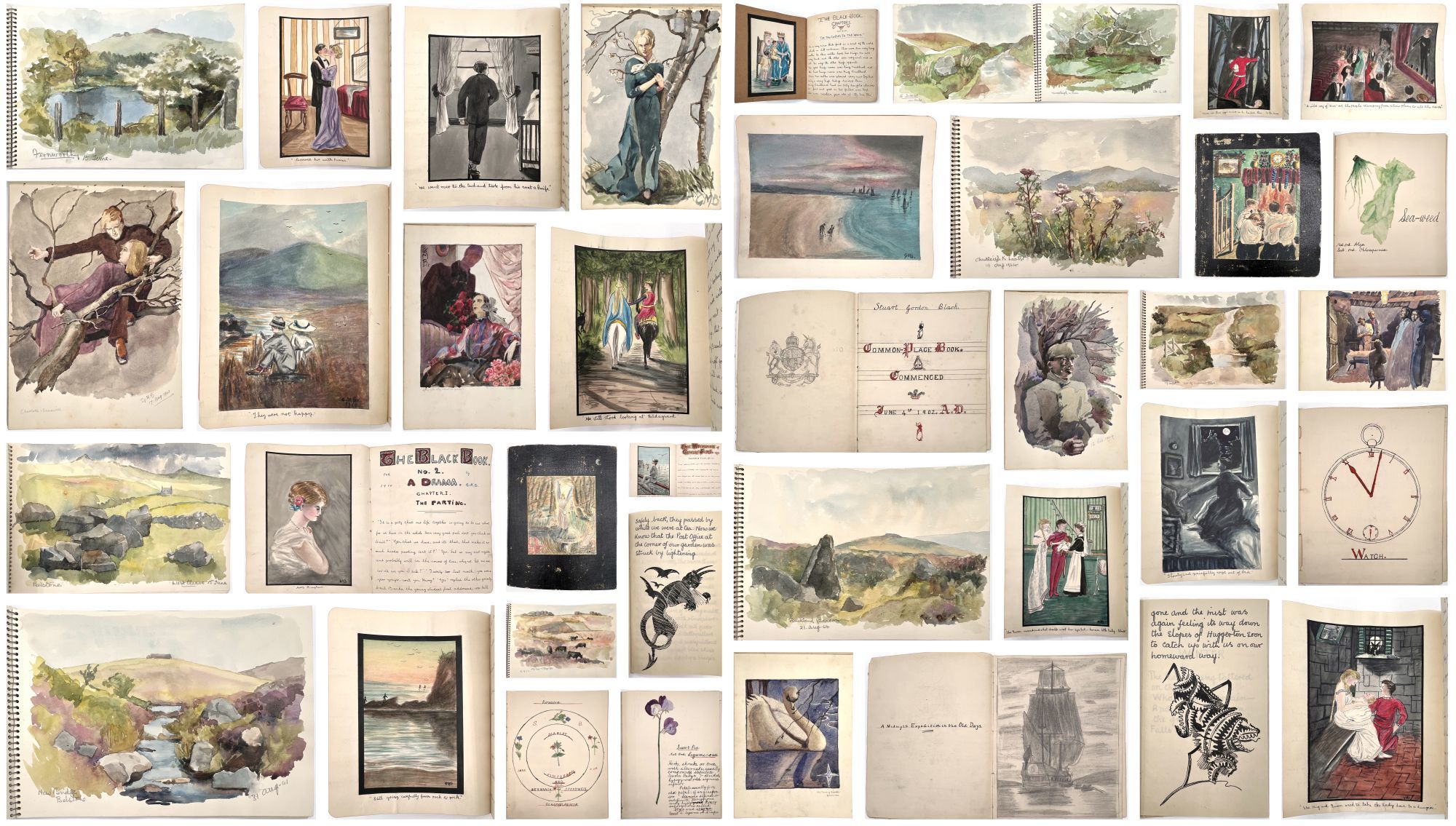

Torquay, Devon, United Kingdom, 1968. Very good. Minor flaws including surface wear, toning, the occasional short tear or loose leaf.. A superlative archive of artwork, short stories, and musings recorded by a woman artist and her two siblings born into an upper-middle class doctor’s family in Torquay, Devon in the 1890s. Spanning the years 1910 to 1968, the archive provides a vivid look into what is a remarkably rich shared imaginative life, fostered by educated parents who understood the value of art, curiosity, and creative expression.

The three siblings are Gladys Mary Black (1895-1979); Stuart Gordon Black (1890-c.1961); and Freda Muriel Black (1896-1976). Stuart Gordon Black became a respected Torquay photographer and member of the Royal Photographic Society as an adult, and served in the First World War in the Royal Air Force, as an x-ray technician and general mechanic. After the war, he married the photographer Laurie Macpherson (1893-1979). Neither of his sisters Gladys nor Freda appear to have married, but both lived in or around Torquay for the remainder of their lives. The parents of these three siblings were George Black, M.D. (1854-1913) and Marion Reid Black (1860-1932). George was a respected physician born in Edinburgh who, ahead of his time, advocated for vegetarian and whole food diets and was against vivisection; he published widely on the subjects, and was a member of the British Homeopathic Society.

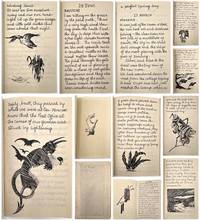

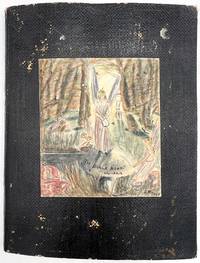

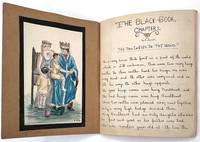

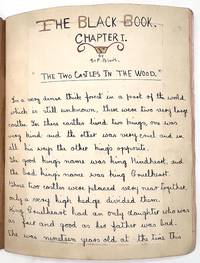

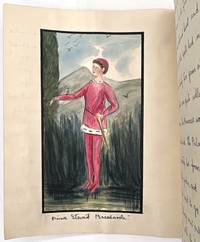

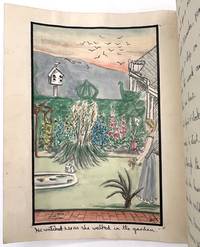

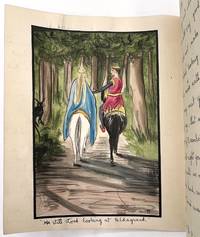

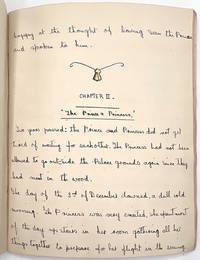

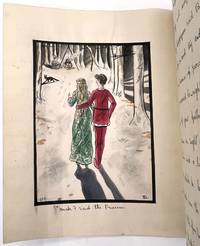

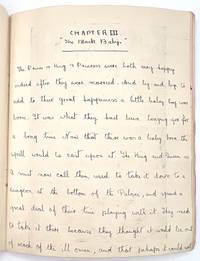

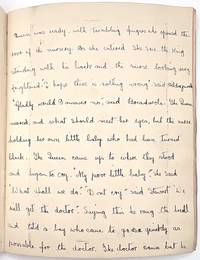

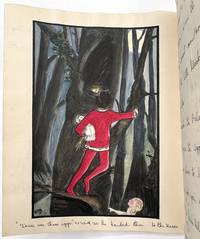

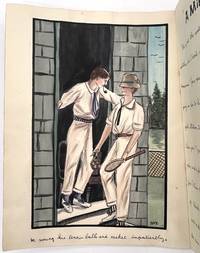

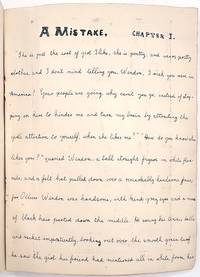

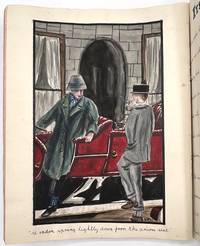

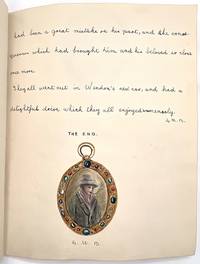

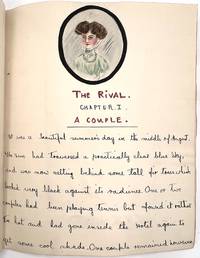

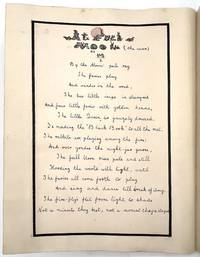

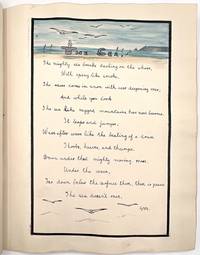

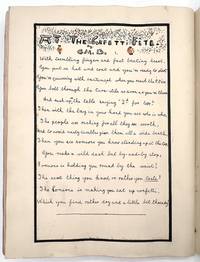

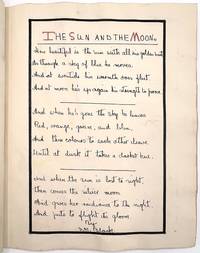

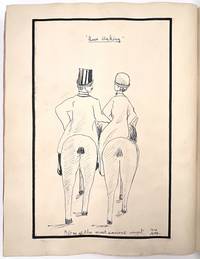

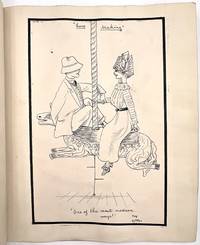

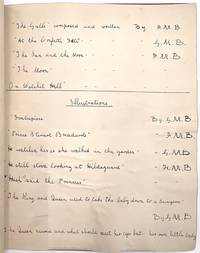

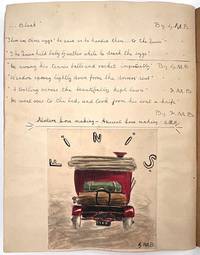

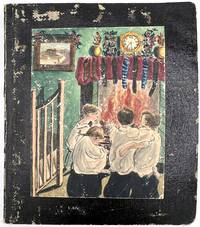

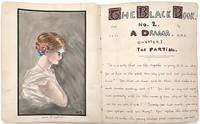

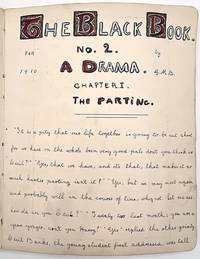

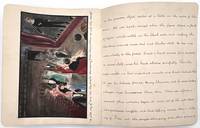

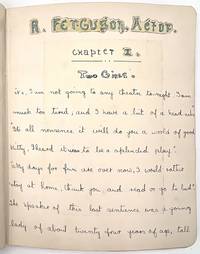

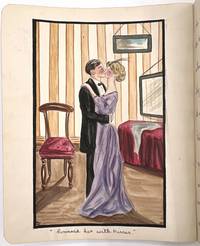

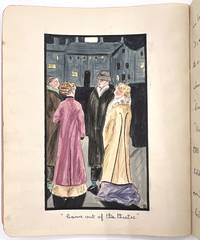

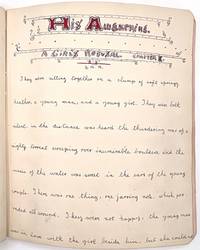

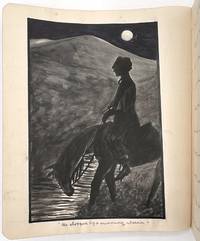

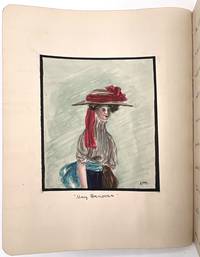

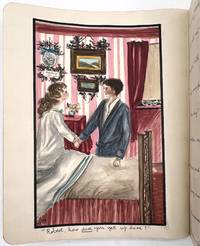

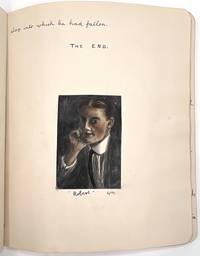

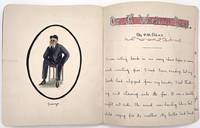

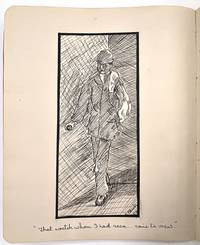

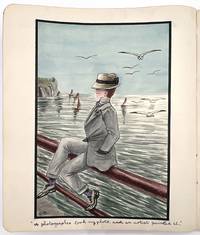

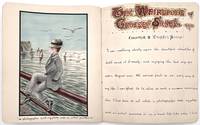

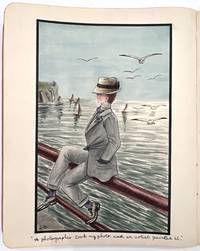

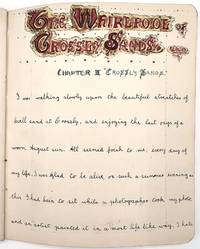

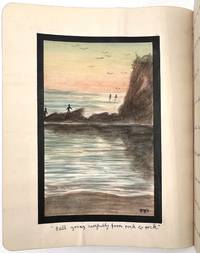

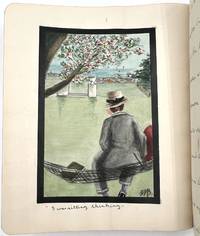

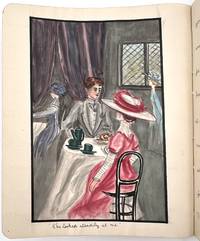

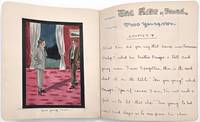

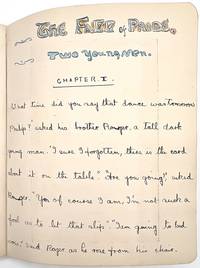

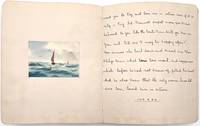

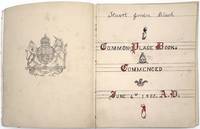

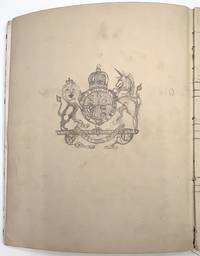

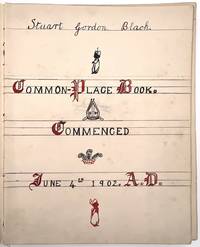

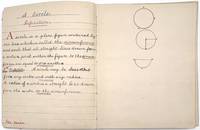

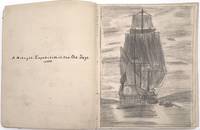

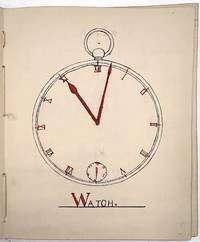

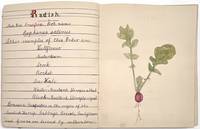

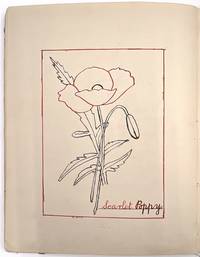

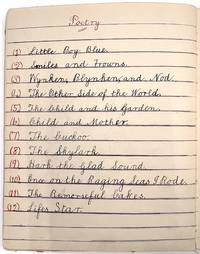

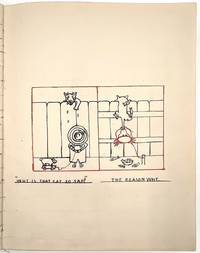

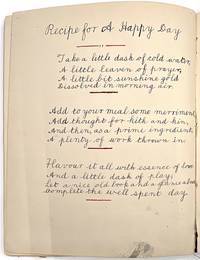

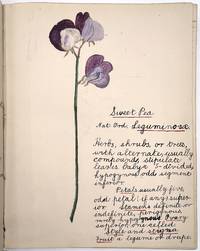

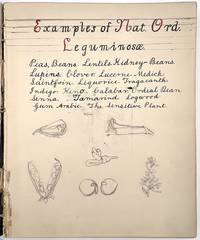

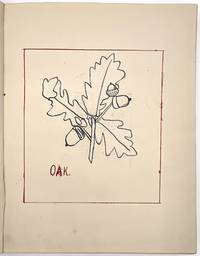

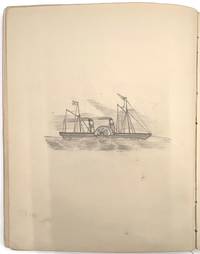

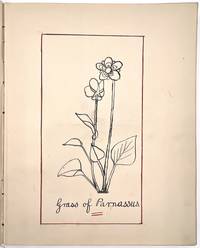

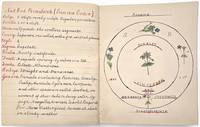

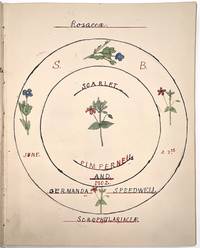

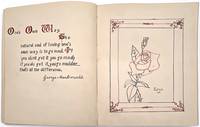

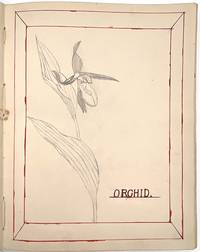

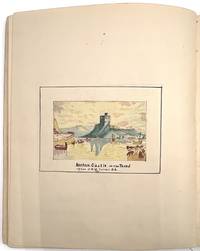

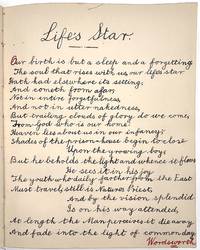

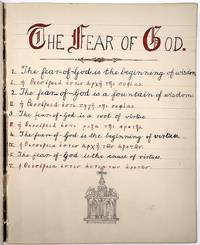

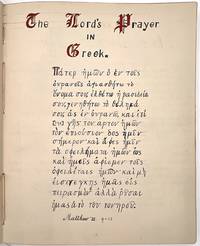

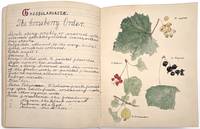

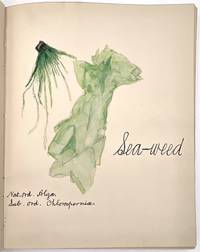

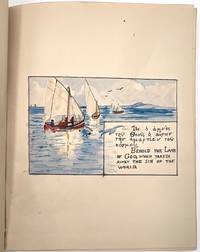

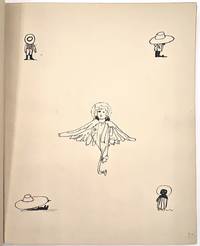

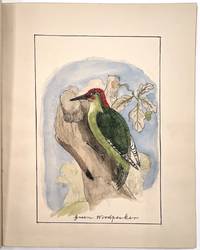

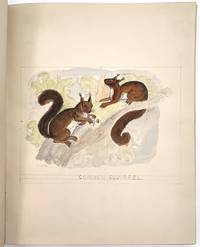

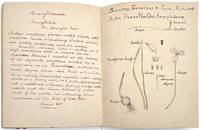

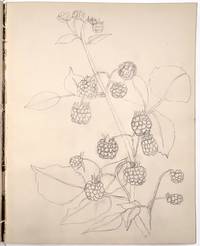

The strength of this archive lies in the vividness with which the siblings’ internal and creative lives are portrayed, as well as a clear sense of Brontë-esque creative collaboration between the two sisters, as evidenced by their so-called “Black Books”. These two books contain original artwork, poetry, and short stories that the girls composed together in 1910, when Gladys was 15 and Freda was 14. Romance, hope, and intrigue fill the pages, alongside bright and dramatic seascapes and characters inspired by the sibling’s hometown of Torquay. In a couple of instances, characters cross over from one story to another, creating a rich shared world (hence the Brontë comparison). The characters, which are depicted in a clearly upper-crust world, court each other and navigate social misunderstandings, nearly always living happily ever after in handsome well-to-do couplings at the end. Drama occurs only to bring couples closer together, or to provide the gentleman with an opportunity to prove his chivalry and bravery. It is impossible to read these stories and not feel the earnest hopes and dreams of these two passionate teenage girls. Another highlight of the archive includes their brother Stuart’s commonplace book, which he compiled at age 12. The content of the book illustrates his varied and enthusiastic interests as the educated son of a well-to-do doctor: Greek translations; drawings (plants, animals, trains, a compass, a watch); botanical drawings with scientific facts; geometric drawings and definitions; cartoons; and poetry (quoted, not original).

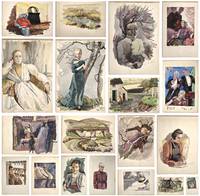

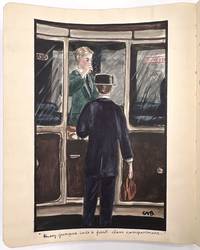

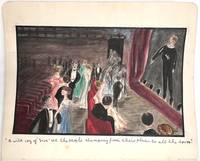

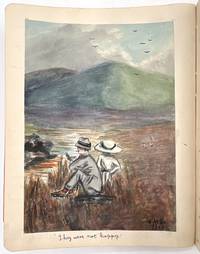

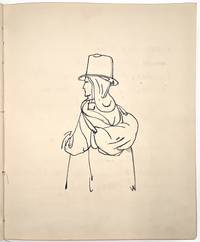

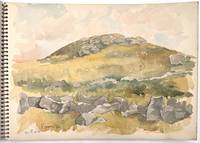

The remaining bulk of the archive is taken up by twelve (12) spiral-bound sketchbooks filled with mature watercolor artwork by Gladys, dated between c.1943, when she was 48 years old, and c.1968, when she was 73. There is an evocative link between her childhood artwork and her mature artwork, particularly in subject; though a grown woman, she clearly continued her passionate love affair with dramatic seascapes, moors, and human nature. Both of her siblings appear in portraiture, revealing their still close relationship. She has an uncanny ability of capturing human expression and thought that is not seen in most amateur watercolor artwork.

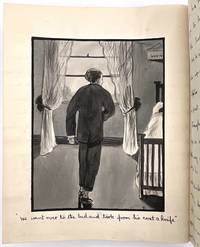

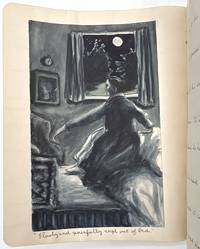

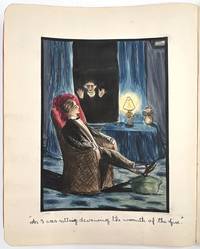

Note well a fascinating evolution the sisters’ perception of Blackness and racial identity. In the 1910 short story “On a Winter’s Night”, it is clear that the girls associate Blackness with fear and the unknown. After all, the likelihood that they would have met any Black people as daughters of a Torquay doctor would have been slim, at best, and they would have primarily formed their impressions of Blackness from popular suspense and romance novels—of which they clearly devoured many. They wrote “On a Winter’s Night” about a young White gentleman who is startled by a shadowy figure outside his window in the dark:

"…he was tall and as I looked I saw he was a negro. He was gazing through the window with a wild and desperate look in his eyes. Seemingly he did not see me, but just seemed to look right through me, and on into the room. I shuddered again ... I looked towards the door, and as my eyes fell upon it I saw it slowly open, and to my intense horror I saw a grimy brown hand appear to view. But worse was to come slowly that wretch whom I had seen outside came to view. He did not seem to observe me, his eyes were fastened on another object … little by little he cleared all the valuable things off the sideboard into the sack which he carried…”

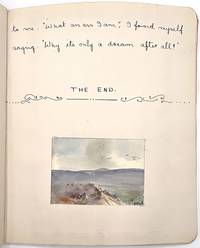

The onlooker, speechless in horror, watches as the burglar makes off with the valuables, and demonstrates a horrifying ability to walk through locked doors. It is only when the protagonist awakens that it is revealed that it was all a dream, a figment of an overactive imagination. Obviously, the girls—who, again, probably had never even seen a Black man in real life—associated Blackness with fear, suspense, and danger. But we see that perception shift sharply when we look at Gladys’ mature watercolor artwork. In an untitled portrait dated 12 Feb. 1944, Gladys paints a Black soldier from the Second World War in an unmistakably handsome light; Blackness now, it seems, is beautiful, and no longer frightening. Not two leaves later, she paints a group of men in what appears to be a cellar; two White men in cold and distant poses and expressions, contrasted with three Black men with fearful and conflicted expressions. It is unclear what specifically Gladys is trying to say about race here (if anything), but it is clear that she has developed a nuanced and curious interest in race and human nature.

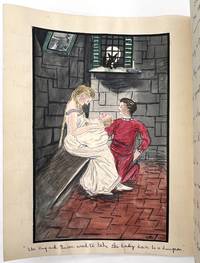

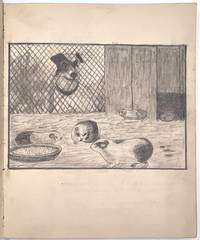

One of the more unusual stories from the girls’ childhood “Black Books” is titled “The Two Castles in the Wood” and involves, again, and interesting fear of darkness/Blackness on the part of the girls. It begins with two castles, one ruled by King Cruelheart, the other by King Kindheart. King Cruelheart’s beautiful daughter falls in love with King Kindheart’s son, and they marry. Blackness appears first as a bad omen: a black cat, watching the couple from the edges of the story, and literally watching them from the outskirts of the accompanying illustrations. It becomes clear that the cat represents King Cruelheart’s desire to control his daughter, and keep her from marrying her lover. And when they finally do, and have a baby, it is revealed that the baby is cursed: “The Queen neared, and what should meet her eyes, but the nurse holding her own little baby who had been turned black … the doctor came but he shook his head”. Cue several days of misery, until they find a way to break the curse by having the baby drink owl eggs, and turn white again. The black cat’s curse is lifted, and the family live happily ever after with their white baby.

As noted earlier, there is an interesting interplay between the short stories, which often seem to occupy the same imagined world. The name “Maclair” appears in at least two stories, for example, and offer loose ties between characters. Another interesting example of the stories’ connections can be seen in the two stories titled “The Fall of Pride” and “The Whirlpool of Crossly”. “The Fall of Pride” tells the story of a young man who take a girl out boating. They crash into some rocks, and he loses consciousness; it is revealed later in the hospital that she lost her life. This plot point becomes relevant in the other story, “Whirlpool”, in that a small white hand is seen luring people into the water, causing a sailor to drown and others to nearly drown. Thankfully, “Whirlpool” ends with the protagonist saving his love interest from the same fate as the first girl, but the reader is left with a deliciously haunting realization that ghostly intentions are afoot. You can almost hear the teenage girls who wrote these stories telling them to each other in hushed voices after bedtime, giggling and gasping in equal turns. And note, of course, the clear connection between their love of nature and the seaside of Torquay to these stories.

The remainder of Gladys’ artwork and her undated commonplace book in this archive similarly show her deep passion for nature (in, again, a very Brontë-esque manner, point of view, and aesthetic). The undated commonplace book charts her rambles throughout Dartmoor National Park, with rich detail: “It has been dark and grey all day with a brooding mist which has never lifted. About five in the evening we drove to Fernworthy. As we climbed to the moor through the first gate the mist was a soundless blanket enfolding all but. The nearest objects, the rocks, sheep and ponies were ghosts which we dimly saw…” Her sketchbooks are filled with similar impressions, albeit in a visual format: watercolors of dramatic moors, sea and landscapes.

The archive provides an evocative view into the development of an artist, with rare insight into her childhood wishes, dreams, and relationships.

The physical description of this archive is as follows:

In total there are sixteen (16) bound volumes, each with approx. 100-200 leaves each. The largest measures approx. 10” by 14”, and the smallest measures approx. 7.25” by 4.5”. Twelve (12) of the volumes are sketchbooks with original watercolor and pencil artwork by Gladys; there are also two (2) black commonplace books created by Gladys and Freda, one (1) commonplace book kept by Gladys, and one (1) commonplace book kept by Stuart. In total, there are 9 original short stories, 7 original poems, over 200 original sketches and watercolors, and dozens of miscellaneous musings and sketches. The archive can be housed in less than one (1) linear foot of shelf space. They range in date from 1910 to 1968.

The three siblings are Gladys Mary Black (1895-1979); Stuart Gordon Black (1890-c.1961); and Freda Muriel Black (1896-1976). Stuart Gordon Black became a respected Torquay photographer and member of the Royal Photographic Society as an adult, and served in the First World War in the Royal Air Force, as an x-ray technician and general mechanic. After the war, he married the photographer Laurie Macpherson (1893-1979). Neither of his sisters Gladys nor Freda appear to have married, but both lived in or around Torquay for the remainder of their lives. The parents of these three siblings were George Black, M.D. (1854-1913) and Marion Reid Black (1860-1932). George was a respected physician born in Edinburgh who, ahead of his time, advocated for vegetarian and whole food diets and was against vivisection; he published widely on the subjects, and was a member of the British Homeopathic Society.

The strength of this archive lies in the vividness with which the siblings’ internal and creative lives are portrayed, as well as a clear sense of Brontë-esque creative collaboration between the two sisters, as evidenced by their so-called “Black Books”. These two books contain original artwork, poetry, and short stories that the girls composed together in 1910, when Gladys was 15 and Freda was 14. Romance, hope, and intrigue fill the pages, alongside bright and dramatic seascapes and characters inspired by the sibling’s hometown of Torquay. In a couple of instances, characters cross over from one story to another, creating a rich shared world (hence the Brontë comparison). The characters, which are depicted in a clearly upper-crust world, court each other and navigate social misunderstandings, nearly always living happily ever after in handsome well-to-do couplings at the end. Drama occurs only to bring couples closer together, or to provide the gentleman with an opportunity to prove his chivalry and bravery. It is impossible to read these stories and not feel the earnest hopes and dreams of these two passionate teenage girls. Another highlight of the archive includes their brother Stuart’s commonplace book, which he compiled at age 12. The content of the book illustrates his varied and enthusiastic interests as the educated son of a well-to-do doctor: Greek translations; drawings (plants, animals, trains, a compass, a watch); botanical drawings with scientific facts; geometric drawings and definitions; cartoons; and poetry (quoted, not original).

The remaining bulk of the archive is taken up by twelve (12) spiral-bound sketchbooks filled with mature watercolor artwork by Gladys, dated between c.1943, when she was 48 years old, and c.1968, when she was 73. There is an evocative link between her childhood artwork and her mature artwork, particularly in subject; though a grown woman, she clearly continued her passionate love affair with dramatic seascapes, moors, and human nature. Both of her siblings appear in portraiture, revealing their still close relationship. She has an uncanny ability of capturing human expression and thought that is not seen in most amateur watercolor artwork.

Note well a fascinating evolution the sisters’ perception of Blackness and racial identity. In the 1910 short story “On a Winter’s Night”, it is clear that the girls associate Blackness with fear and the unknown. After all, the likelihood that they would have met any Black people as daughters of a Torquay doctor would have been slim, at best, and they would have primarily formed their impressions of Blackness from popular suspense and romance novels—of which they clearly devoured many. They wrote “On a Winter’s Night” about a young White gentleman who is startled by a shadowy figure outside his window in the dark:

"…he was tall and as I looked I saw he was a negro. He was gazing through the window with a wild and desperate look in his eyes. Seemingly he did not see me, but just seemed to look right through me, and on into the room. I shuddered again ... I looked towards the door, and as my eyes fell upon it I saw it slowly open, and to my intense horror I saw a grimy brown hand appear to view. But worse was to come slowly that wretch whom I had seen outside came to view. He did not seem to observe me, his eyes were fastened on another object … little by little he cleared all the valuable things off the sideboard into the sack which he carried…”

The onlooker, speechless in horror, watches as the burglar makes off with the valuables, and demonstrates a horrifying ability to walk through locked doors. It is only when the protagonist awakens that it is revealed that it was all a dream, a figment of an overactive imagination. Obviously, the girls—who, again, probably had never even seen a Black man in real life—associated Blackness with fear, suspense, and danger. But we see that perception shift sharply when we look at Gladys’ mature watercolor artwork. In an untitled portrait dated 12 Feb. 1944, Gladys paints a Black soldier from the Second World War in an unmistakably handsome light; Blackness now, it seems, is beautiful, and no longer frightening. Not two leaves later, she paints a group of men in what appears to be a cellar; two White men in cold and distant poses and expressions, contrasted with three Black men with fearful and conflicted expressions. It is unclear what specifically Gladys is trying to say about race here (if anything), but it is clear that she has developed a nuanced and curious interest in race and human nature.

One of the more unusual stories from the girls’ childhood “Black Books” is titled “The Two Castles in the Wood” and involves, again, and interesting fear of darkness/Blackness on the part of the girls. It begins with two castles, one ruled by King Cruelheart, the other by King Kindheart. King Cruelheart’s beautiful daughter falls in love with King Kindheart’s son, and they marry. Blackness appears first as a bad omen: a black cat, watching the couple from the edges of the story, and literally watching them from the outskirts of the accompanying illustrations. It becomes clear that the cat represents King Cruelheart’s desire to control his daughter, and keep her from marrying her lover. And when they finally do, and have a baby, it is revealed that the baby is cursed: “The Queen neared, and what should meet her eyes, but the nurse holding her own little baby who had been turned black … the doctor came but he shook his head”. Cue several days of misery, until they find a way to break the curse by having the baby drink owl eggs, and turn white again. The black cat’s curse is lifted, and the family live happily ever after with their white baby.

As noted earlier, there is an interesting interplay between the short stories, which often seem to occupy the same imagined world. The name “Maclair” appears in at least two stories, for example, and offer loose ties between characters. Another interesting example of the stories’ connections can be seen in the two stories titled “The Fall of Pride” and “The Whirlpool of Crossly”. “The Fall of Pride” tells the story of a young man who take a girl out boating. They crash into some rocks, and he loses consciousness; it is revealed later in the hospital that she lost her life. This plot point becomes relevant in the other story, “Whirlpool”, in that a small white hand is seen luring people into the water, causing a sailor to drown and others to nearly drown. Thankfully, “Whirlpool” ends with the protagonist saving his love interest from the same fate as the first girl, but the reader is left with a deliciously haunting realization that ghostly intentions are afoot. You can almost hear the teenage girls who wrote these stories telling them to each other in hushed voices after bedtime, giggling and gasping in equal turns. And note, of course, the clear connection between their love of nature and the seaside of Torquay to these stories.

The remainder of Gladys’ artwork and her undated commonplace book in this archive similarly show her deep passion for nature (in, again, a very Brontë-esque manner, point of view, and aesthetic). The undated commonplace book charts her rambles throughout Dartmoor National Park, with rich detail: “It has been dark and grey all day with a brooding mist which has never lifted. About five in the evening we drove to Fernworthy. As we climbed to the moor through the first gate the mist was a soundless blanket enfolding all but. The nearest objects, the rocks, sheep and ponies were ghosts which we dimly saw…” Her sketchbooks are filled with similar impressions, albeit in a visual format: watercolors of dramatic moors, sea and landscapes.

The archive provides an evocative view into the development of an artist, with rare insight into her childhood wishes, dreams, and relationships.

The physical description of this archive is as follows:

In total there are sixteen (16) bound volumes, each with approx. 100-200 leaves each. The largest measures approx. 10” by 14”, and the smallest measures approx. 7.25” by 4.5”. Twelve (12) of the volumes are sketchbooks with original watercolor and pencil artwork by Gladys; there are also two (2) black commonplace books created by Gladys and Freda, one (1) commonplace book kept by Gladys, and one (1) commonplace book kept by Stuart. In total, there are 9 original short stories, 7 original poems, over 200 original sketches and watercolors, and dozens of miscellaneous musings and sketches. The archive can be housed in less than one (1) linear foot of shelf space. They range in date from 1910 to 1968.