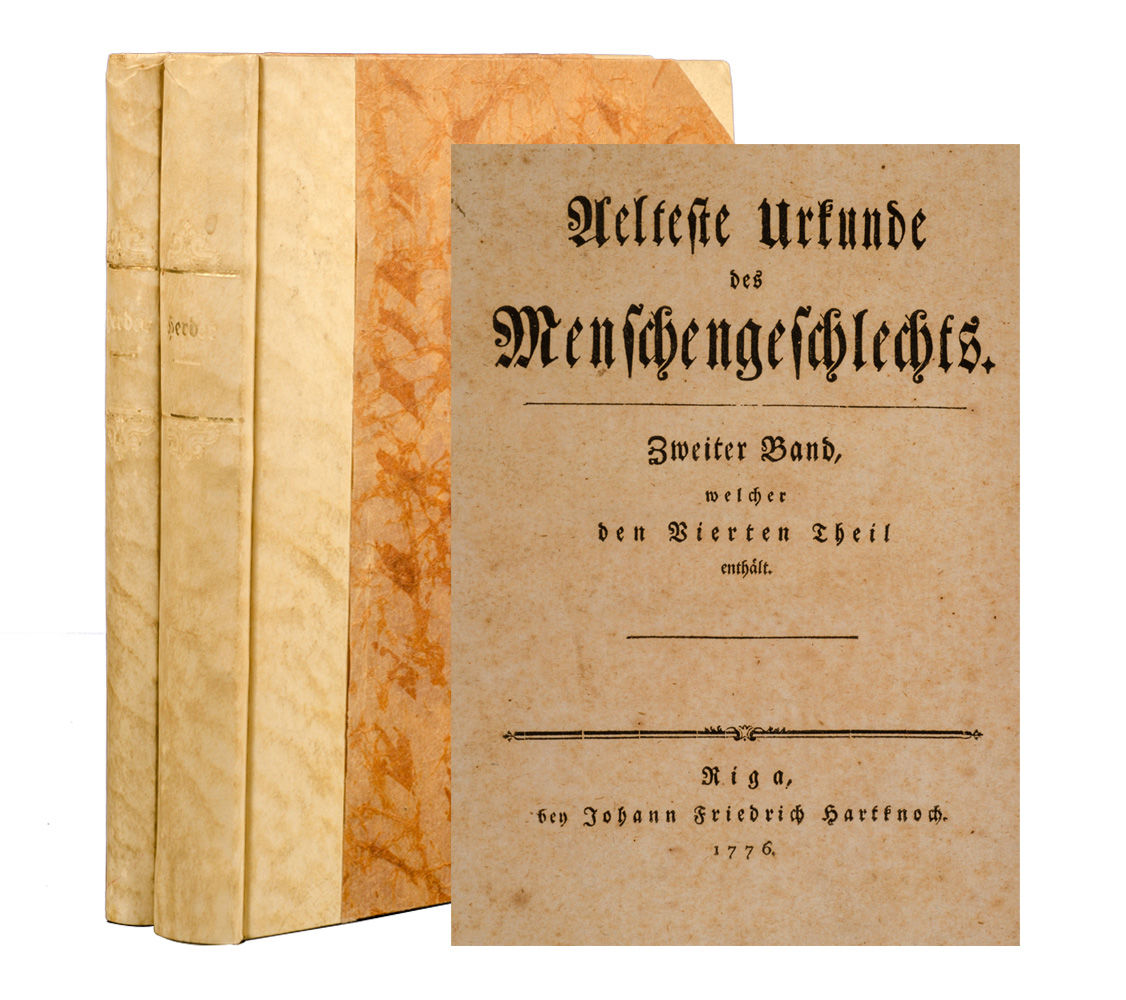

Aelteste Urkunde des Menschengeschlechts (in 2 vols.)

- Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1776

Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1776. First edition. Two quarto volumes (9 1/2 x 7 3/4 inches; 241 x 195 mm.). [iv], 384; [viii], 202 pp. Late nineteenth century parchment over decorated paper boards, spines lettered and ruled in gilt.

Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803) was a philosopher and literary critic, whose writings were instrumental in forming European romanticism. As the leader of the Sturm und Drang movement, he inspired many writers, notably Goethe, the future leader of the German Romantics (Britannica). Aelteste Urkunde des Menschengeschlechts (which translates to The Oldest Document of the Human Race), is a fascinating work on cosmogany and The Old Testament. Herder says in an earlier version of his Aelteste Urkunde, around 1771 or 1772: "Aber so wissen wir ja nicht das Alter der Welt!" (But we do not know the age of the world). The Book of Genesis, he says, can give us no information on this subject. But in 1774, in the final version of the same work, he says that "die Welt fast sechstausend Jahr alt… ist" (The world is almost six thousand years old). In a sermon of the same year, he says of the three Magi: "… viertausend oder Eins oder Zwei wars, da die Weisen ankamen" (…four thousand years and one or two wars, then came the wise men). Thus it appears that during his most religious phase, he came to accept the Biblical chronology that he had rejected two or three years previously.

Herder takes issue with Kircher's work throughout the text: Twice in "Aegyptische Götterlehre... Herder couples Kircher’s name with that of Huet, and both times stresses the unreliability of the Jesuit’s work. Herder also critiqued earlier pioneers in the field of Egyptian studies and lumped indiscriminately together the varied honest efforts that had helped to spread in Europe a first-hand knowledge of the hieroglyphs" (Fletcher). The author utilizes a jibing style throughout, especially when expressing his belief that Kircher had made willful fabrications. "The last reference to Kircher in this work is more justified. Herder expresses the idea that perhaps, after all, the Egyptian obelisks and other inscribed monuments were not the repositories of divine wisdom Kircher thought they were. In this, Herder follows Leibniz (Accessiones historicae) and precedes Zoega (De origine et usu obeliscorum). Herder returned to his derogatory ‘Kirchersche Träume’ for a brief moment some fifteen years later when giving a reference for the work most suitable on the early origin of speech: ‘Die beste Schrift fur dise noch zum Theil unausgearbeitete Materie ist Wachteri naturae et scripturae concordia die sich von der Kircherschen und so viel andern Träumen, wie Alterthumsgeschichte von Märchen unterscheidet’. Herder refers here to Kircher’s views, admittedly a little ingenuous, on the production of sound, contained in his Musurgia of 1650. More alarming than Herder’s academic disagreement is the fact that he seems perfectly ready to use his expression ‘Kirchersche Träume’ in a manner that is more generic than specific. It is perhaps fortunate, at least as far as the Jesuit’s ragged reputation was concerned, that Herder made no more academic references to his works" (Fletcher).

Johann Gottfried von Herder (1744-1803) was a philosopher and literary critic, whose writings were instrumental in forming European romanticism. As the leader of the Sturm und Drang movement, he inspired many writers, notably Goethe, the future leader of the German Romantics (Britannica). Aelteste Urkunde des Menschengeschlechts (which translates to The Oldest Document of the Human Race), is a fascinating work on cosmogany and The Old Testament. Herder says in an earlier version of his Aelteste Urkunde, around 1771 or 1772: "Aber so wissen wir ja nicht das Alter der Welt!" (But we do not know the age of the world). The Book of Genesis, he says, can give us no information on this subject. But in 1774, in the final version of the same work, he says that "die Welt fast sechstausend Jahr alt… ist" (The world is almost six thousand years old). In a sermon of the same year, he says of the three Magi: "… viertausend oder Eins oder Zwei wars, da die Weisen ankamen" (…four thousand years and one or two wars, then came the wise men). Thus it appears that during his most religious phase, he came to accept the Biblical chronology that he had rejected two or three years previously.

Herder takes issue with Kircher's work throughout the text: Twice in "Aegyptische Götterlehre... Herder couples Kircher’s name with that of Huet, and both times stresses the unreliability of the Jesuit’s work. Herder also critiqued earlier pioneers in the field of Egyptian studies and lumped indiscriminately together the varied honest efforts that had helped to spread in Europe a first-hand knowledge of the hieroglyphs" (Fletcher). The author utilizes a jibing style throughout, especially when expressing his belief that Kircher had made willful fabrications. "The last reference to Kircher in this work is more justified. Herder expresses the idea that perhaps, after all, the Egyptian obelisks and other inscribed monuments were not the repositories of divine wisdom Kircher thought they were. In this, Herder follows Leibniz (Accessiones historicae) and precedes Zoega (De origine et usu obeliscorum). Herder returned to his derogatory ‘Kirchersche Träume’ for a brief moment some fifteen years later when giving a reference for the work most suitable on the early origin of speech: ‘Die beste Schrift fur dise noch zum Theil unausgearbeitete Materie ist Wachteri naturae et scripturae concordia die sich von der Kircherschen und so viel andern Träumen, wie Alterthumsgeschichte von Märchen unterscheidet’. Herder refers here to Kircher’s views, admittedly a little ingenuous, on the production of sound, contained in his Musurgia of 1650. More alarming than Herder’s academic disagreement is the fact that he seems perfectly ready to use his expression ‘Kirchersche Träume’ in a manner that is more generic than specific. It is perhaps fortunate, at least as far as the Jesuit’s ragged reputation was concerned, that Herder made no more academic references to his works" (Fletcher).