Court Duplicate of the Testimony of Thomas Kent, a Black Man Aboard the Brigantine Britannia When It Wrecked off the Coast of New Brunswick in December of 1834

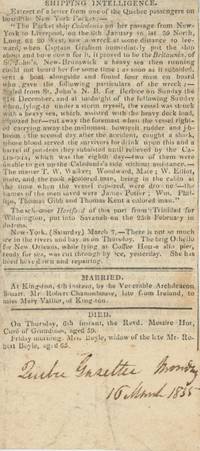

- Three 8 x 13 inch pages, folded. Toning at folds; fine. With a clipping from the Quebec Gazette Monthly, March 1835

- St. John, New Brunswick, British North America , 1835

St. John, New Brunswick, British North America, 1835. Three 8 x 13 inch pages, folded. Toning at folds; fine. With a clipping from the Quebec Gazette Monthly, March 1835. Fine. Little biographical information is available on Thomas Kent, save that he was a sailor aboard the Britannia and that the newspaper clipping included here identifies him as “a colored man.” Offered here is a notarized copy of Kent’s testimony concerning the wreck of the Britannia and the consequent deaths of its Captain Thomas Millidge Walker, its mates Woodward and Elliot, and its cook George Monroe, who was also a Black man.

The Britannia was owned by New Brunswick merchants Isaac and John G. Woodward, who may have requested the notarized testimony for insurance purposes: the notary writes that it was written on their behalf, and emphasizes that:

“That the capsizing of the said Brigantine and her subsequent loss, arose solely from the excessive violence of the Gale and a tremendous Sea, and not from any default or negligence of the Captain or Crew.”

The ship had sailed from New Brunswick on December 21, 1834, for Berbice, in Dutch Guyana, with a load of lumber and fish. Six days later, the ship’s trials began. Kent testifies that the Britannia:

“was hove to in a violent gale of wind from the north West; that a few minutes before midnight, a very heavy sea, struck her and capsized her on her beam-ends; [...] That this appearer [i.e., Kent] was washed overboard when the sea struck the vessel but fortunately succeeded in getting on board again when he discovered three other Seamen on Deck.”

According to the clipping, the other survivors were James Potter, William Phillips, and Thomas Gibb. They survived solely because they had been on deck; the others “being below were drowned in the Cabin.”

The storm began to let up the next morning, but “this appearer and the other three Seamen remained on the wreck nine days nearly all [of] which time it blew a gale of wind.” The men survived “by their fortunately catching a shark on which and a few potatoes that floated up from below, they subsisted.” After nine days, they were rescued by the Caledonia, a packet ship traveling from New York to Liverpool. Arriving in Liverpool three weeks later, the men are still not recovered from the ordeal:

“one of the Seamen saved afterwards died in the Infirmary at Liverpool from fatigue and exposure; [...] this appearer was also so ill in Liverpool from the same causes that his life was greatly despaired of.”

Overall a harrowing account, of interest to scholars of maritime history and Canadian history, and of Black people’s roles therein.

The Britannia was owned by New Brunswick merchants Isaac and John G. Woodward, who may have requested the notarized testimony for insurance purposes: the notary writes that it was written on their behalf, and emphasizes that:

“That the capsizing of the said Brigantine and her subsequent loss, arose solely from the excessive violence of the Gale and a tremendous Sea, and not from any default or negligence of the Captain or Crew.”

The ship had sailed from New Brunswick on December 21, 1834, for Berbice, in Dutch Guyana, with a load of lumber and fish. Six days later, the ship’s trials began. Kent testifies that the Britannia:

“was hove to in a violent gale of wind from the north West; that a few minutes before midnight, a very heavy sea, struck her and capsized her on her beam-ends; [...] That this appearer [i.e., Kent] was washed overboard when the sea struck the vessel but fortunately succeeded in getting on board again when he discovered three other Seamen on Deck.”

According to the clipping, the other survivors were James Potter, William Phillips, and Thomas Gibb. They survived solely because they had been on deck; the others “being below were drowned in the Cabin.”

The storm began to let up the next morning, but “this appearer and the other three Seamen remained on the wreck nine days nearly all [of] which time it blew a gale of wind.” The men survived “by their fortunately catching a shark on which and a few potatoes that floated up from below, they subsisted.” After nine days, they were rescued by the Caledonia, a packet ship traveling from New York to Liverpool. Arriving in Liverpool three weeks later, the men are still not recovered from the ordeal:

“one of the Seamen saved afterwards died in the Infirmary at Liverpool from fatigue and exposure; [...] this appearer was also so ill in Liverpool from the same causes that his life was greatly despaired of.”

Overall a harrowing account, of interest to scholars of maritime history and Canadian history, and of Black people’s roles therein.