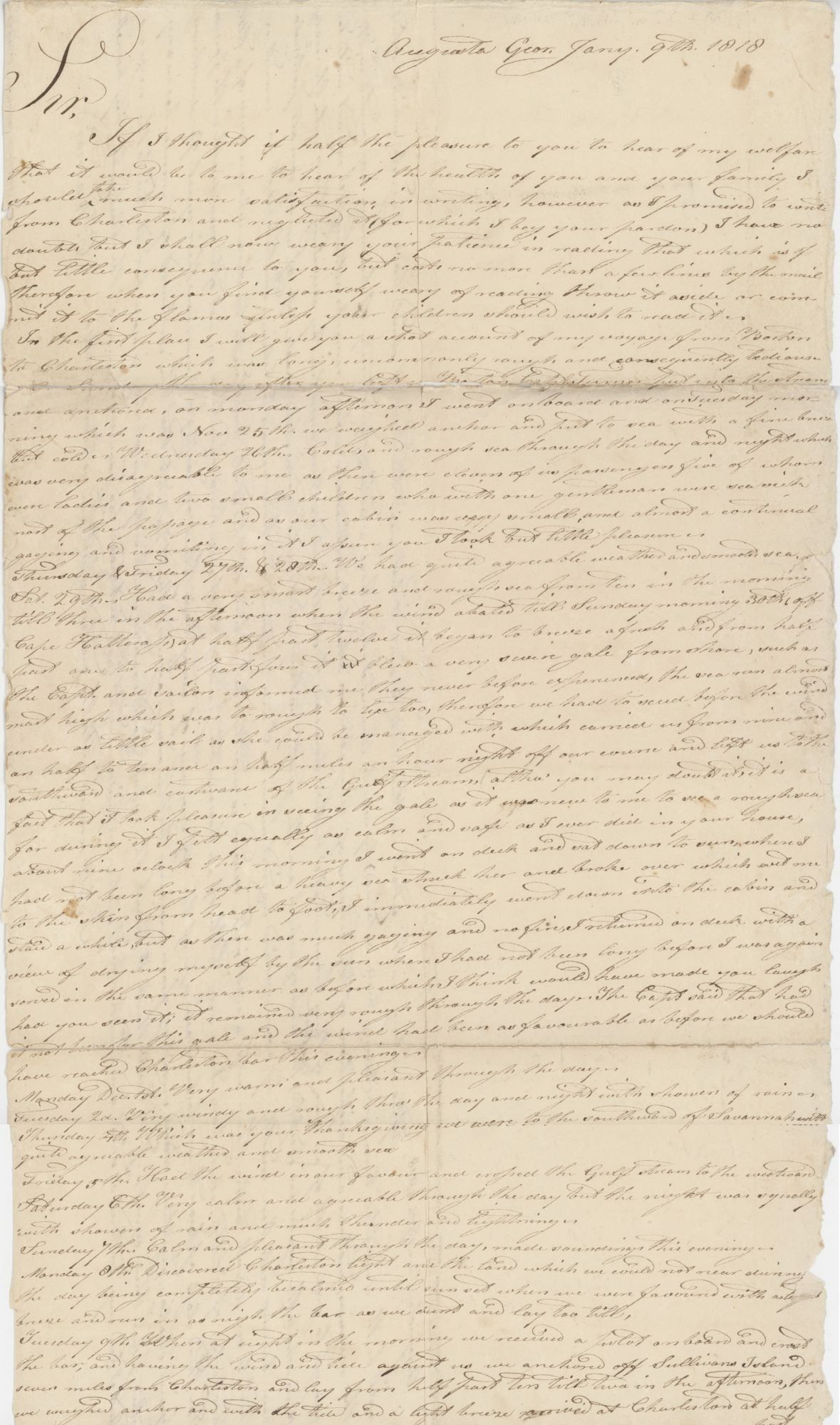

A Letter Written from Augusta, Georgia, Describing the Author’s Voyage from Boston to Augusta, Georgia in 1818

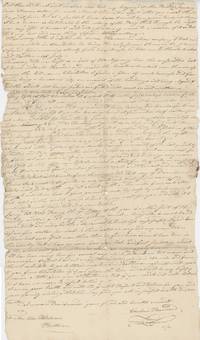

- Single letter, three 9 x 16 inch pages, letters with some tape repairs and stray holes at folds, still quite legible

- Augusta, Georgia , 1818

Augusta, Georgia, 1818. Single letter, three 9 x 16 inch pages, letters with some tape repairs and stray holes at folds, still quite legible. Very good. A letter written by Calvin Barnard to his friend Asa Holman of Bolton, Massachusetts, describing the former’s trip from Boston to Augusta, South Carolina from November 25 to January 1. Barnard first traveled from Boston to Charleston, South Carolina, by boat, from which he notes “almost a continual gagging and vomiting” from the passengers. In Charleston, Barnard observes that the city is inelegant, the unpaved streets “filled with mud”, and views “the breastworks which were thrown up during the last war”. This would have been the War of 1812, of which Barnard was likely a veteran. South Carolina had engaged upwards of 5,000 soldiers and had put up defenses along the coastline in anticipation of the war, but it did not come to the mainland – although South Carolina was under naval blockade, and the Sea Islands were targeted by the British.

Barnard reaches Savannah, Georgia, on the 25th of December; similarly, he finds it “although a place of considerable business”, “about as dissatisfactory a place I ever was in.” Augusta, which he reaches by foot, “is much handsomer built and situated than Savannah but not less dissipated” – he remarks that “Being the first day of the year is in this part of the country another great day for getting drunk.” After spending some time in Augusta, he finishes the letter with some pointed observations about its residents:

“I have had a better opportunity of becoming acquainted with the manners, customs, and dispositions of the citizens of Augusta [...] I shall not do them injustice by dividing them into three classes (in which the Negroes are excepted). The first class of which are the gentry as they would expect to be called, made up of men from all parts who have become rich here, mostly by avaricious and unjust means [...] And this class we cannot expect to see drink more than once a week. The second is mostly the natives of this state and South Carolina, who are men of a little property, of a little education and very little of an honorable principle of any kind, and these are not often seen drunk in the forenoon. The third class appears to me to be made up of the off-scouring of every bad place on earth, for I never saw their equal for drunkenness, lying, stealing, fighting, swearing from morning till morning again. It is not possible that the continent of America has in any other place their equal. If it had, I think the whole world soon be sunk.”

He finds Augusta’s African-American residents the only trustworthy ones, despite local opinions:

“If any stealing is done here, it is laid to the Negroes, but I had my surtout, a shirt, and handkerchief stolen on Friday night last, but have too good an opinion of the blacks to [think] they have them.”

Of interest as an outsider’s views on the early Antebellum South and on drinking – another pressing social issue of the day.

Barnard reaches Savannah, Georgia, on the 25th of December; similarly, he finds it “although a place of considerable business”, “about as dissatisfactory a place I ever was in.” Augusta, which he reaches by foot, “is much handsomer built and situated than Savannah but not less dissipated” – he remarks that “Being the first day of the year is in this part of the country another great day for getting drunk.” After spending some time in Augusta, he finishes the letter with some pointed observations about its residents:

“I have had a better opportunity of becoming acquainted with the manners, customs, and dispositions of the citizens of Augusta [...] I shall not do them injustice by dividing them into three classes (in which the Negroes are excepted). The first class of which are the gentry as they would expect to be called, made up of men from all parts who have become rich here, mostly by avaricious and unjust means [...] And this class we cannot expect to see drink more than once a week. The second is mostly the natives of this state and South Carolina, who are men of a little property, of a little education and very little of an honorable principle of any kind, and these are not often seen drunk in the forenoon. The third class appears to me to be made up of the off-scouring of every bad place on earth, for I never saw their equal for drunkenness, lying, stealing, fighting, swearing from morning till morning again. It is not possible that the continent of America has in any other place their equal. If it had, I think the whole world soon be sunk.”

He finds Augusta’s African-American residents the only trustworthy ones, despite local opinions:

“If any stealing is done here, it is laid to the Negroes, but I had my surtout, a shirt, and handkerchief stolen on Friday night last, but have too good an opinion of the blacks to [think] they have them.”

Of interest as an outsider’s views on the early Antebellum South and on drinking – another pressing social issue of the day.