The Tomb of Tut-Ankh-Amen discovered by the late Earl of Carnarvon and Howard Carter

- London: Cassell & Company Limited, 1923, 1927, 1933

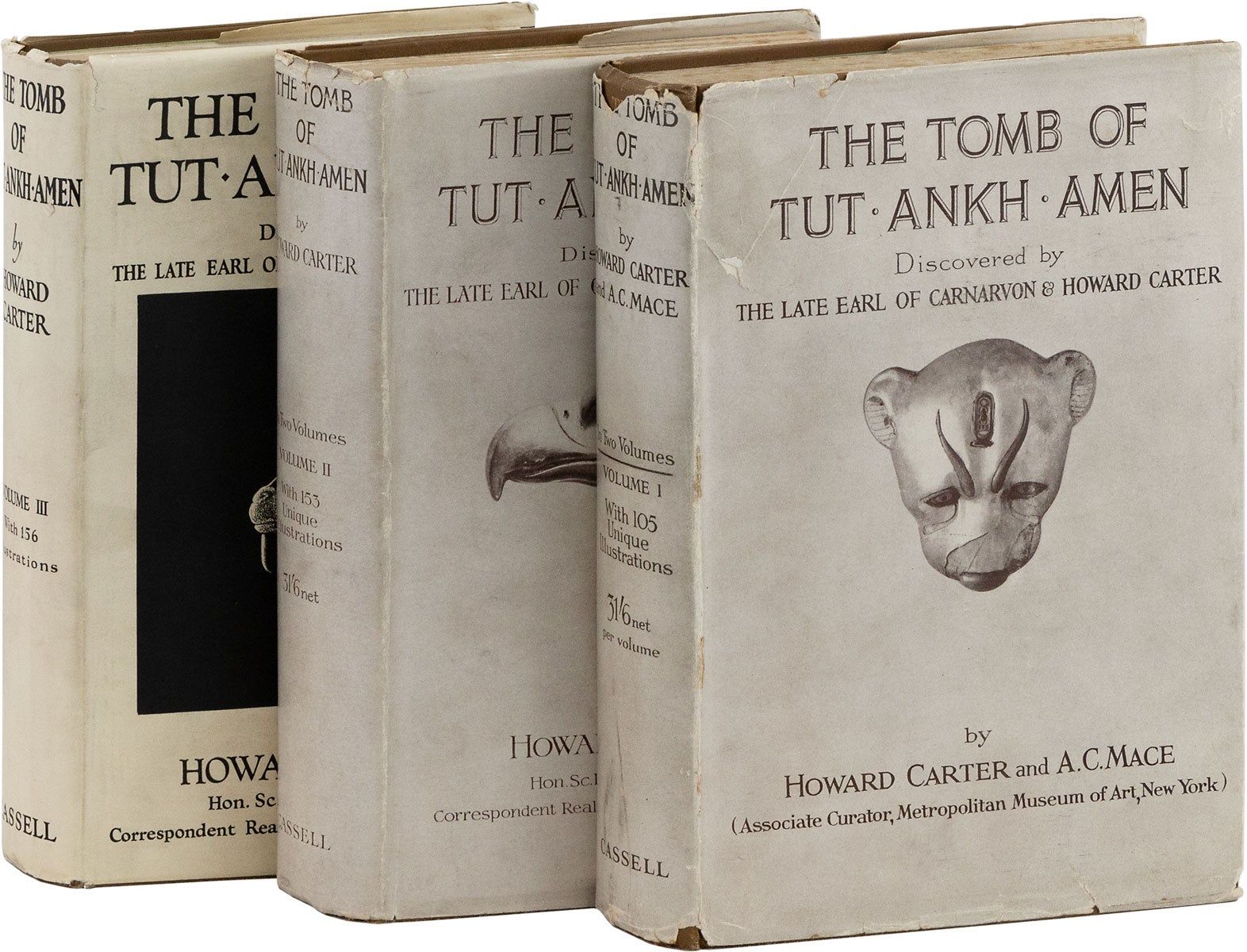

London: Cassell & Company Limited, 1923, 1927, 1933. First Edition. Octavo (24cm). 3 Volumes. Bound in publisher’s original ochre brown cloth titled and decorated in gilt and black to spines and front boards. Dustjackets. [xvi], 231; [xxxiv], 269; [xvi], 247pp. Copiously illustrated throughout all three volumes, a notably 'deluxe' piece of book production. Uniformely very good, sharp, bright copies in cloth with minor shelfwear and bumping, some minor discolouration to the spine of vol. I. This would be a uniformly very handsome set with minimal wear, even without the fact that they are in the original pictorial dustwrappers, clean, bright and unclipped. The dustwrapper of Vol. I has some discolouration and soiling to the front panel, and some marginal chipping, creasing and wear, there is a shallow chip of loss to the head of the spine, just interfering with “The” in the title, which is unfortunate, and a closed tear to the upper left front panel. Vol. II has some light creasing, most notably to the spine panel, but no significant loss or chipping, and Vol. III similarly has some trivial chipping but is otherwise clean and bright, there is some overzealous tape reinforcement to the versos of the dustjackets. A handsome set, of an extremely significant and controversial archaeological text. Scarce in this state.

Without doubt the highest profile and most famous piece of modern archaeological endeavor, rife with professional jealousies, insensitivity to local interests and beliefs, an actual deadly curse, and a grip upon the collective psyche that careens from historical fascination, to incredulous wonder, through endless fictional reworkings and reboots until the complexity, beauty and influence of the discovery has all been rolled together into a series of enduring archaeological memes. Carter himself was famously irascible and very nearly ended his own archaeological career early one with his inability to just get along respectfully with any of the people he worked with, from native Egyptian workers, to other archaeologists. With no formal qualifications, his uncanny ability to find the most incredible treasures became visible in the late 1890's when he was made the first Chief Inspector of Antiquities for the region, which directly led to his discovery of the hidden tomb of Pharoah Thutmose IV in 1903. Unable to persist in a state of calm for longer than ten minutes, in 1905 Carter was compelled to retire from the Antiquities Service after being held responsible for provoking a physical skirmish between a group of foreign visitors and some outraged Egyptian antiquities guards.

“Carter's rehabilitation came in early 1909 when, on the recommendation of Maspero, he began his association with George Herbert, fifth earl of Carnarvon. Until the First World War they excavated in the Theban necropolis, making important, but unspectacular, discoveries.

Carnarvon was then encouraged by Carter to apply for the concession for the Valley of the Kings, surrendered by Davis in 1914. The time was not right, and the prognostications for discovery were not favourable. Davis, Maspero, and others believed that there was nothing of importance left in the valley to be discovered. Carter thought otherwise. A short campaign by Carter in the tomb of King Amenophis III in 1915 produced trifling results, and for the rest of the war until 1917 he was employed as a civilian by the intelligence department of the War Office in Cairo. In 1917 he was at last free to return to working for Carnarvon, and until 1922 he conducted annual campaigns in the Valley of the Kings; but few positive results were achieved.

In the summer of 1922 Carter persuaded Carnarvon to allow him to conduct one more campaign in the valley. Starting work earlier than usual Howard Carter opened up the stairway to the tomb of Tutankhamun on 4 November 1922. Carnarvon hurried to Luxor and the tomb was entered on 26 November. The discovery astounded the world: a royal tomb, mostly undisturbed, full of spectacular objects. Carter recruited a team of expert assistants to help him in the clearance of the tomb, and the conservation and recording of its remarkable contents. On 16 February 1923 the

blocking to the burial chamber was removed, to reveal the unplundered body and funerary equipment of the dead king. Unhappily, the death of Lord Carnarvon on 5 April seriously affected the subsequent progress of Carter's work.

In spite of considerable and repeated bureaucratic interference, not easily managed by the short-tempered excavator, work on the clearance of the tomb proceeded slowly, but was not completed until 1932. Carter handled the technical processes of clearance, conservation, and recording with exemplary skill and care. A popular account of the work was published in three volumes, "The Tomb of Tut-ankh-Amen" (1923–33), the first of which was substantially written by his principal assistant, Arthur C. Mace. No archaeological discovery had met with such sustained public interest, yet Carter received no formal honours from his own country.” (DNB).

Without doubt the highest profile and most famous piece of modern archaeological endeavor, rife with professional jealousies, insensitivity to local interests and beliefs, an actual deadly curse, and a grip upon the collective psyche that careens from historical fascination, to incredulous wonder, through endless fictional reworkings and reboots until the complexity, beauty and influence of the discovery has all been rolled together into a series of enduring archaeological memes. Carter himself was famously irascible and very nearly ended his own archaeological career early one with his inability to just get along respectfully with any of the people he worked with, from native Egyptian workers, to other archaeologists. With no formal qualifications, his uncanny ability to find the most incredible treasures became visible in the late 1890's when he was made the first Chief Inspector of Antiquities for the region, which directly led to his discovery of the hidden tomb of Pharoah Thutmose IV in 1903. Unable to persist in a state of calm for longer than ten minutes, in 1905 Carter was compelled to retire from the Antiquities Service after being held responsible for provoking a physical skirmish between a group of foreign visitors and some outraged Egyptian antiquities guards.

“Carter's rehabilitation came in early 1909 when, on the recommendation of Maspero, he began his association with George Herbert, fifth earl of Carnarvon. Until the First World War they excavated in the Theban necropolis, making important, but unspectacular, discoveries.

Carnarvon was then encouraged by Carter to apply for the concession for the Valley of the Kings, surrendered by Davis in 1914. The time was not right, and the prognostications for discovery were not favourable. Davis, Maspero, and others believed that there was nothing of importance left in the valley to be discovered. Carter thought otherwise. A short campaign by Carter in the tomb of King Amenophis III in 1915 produced trifling results, and for the rest of the war until 1917 he was employed as a civilian by the intelligence department of the War Office in Cairo. In 1917 he was at last free to return to working for Carnarvon, and until 1922 he conducted annual campaigns in the Valley of the Kings; but few positive results were achieved.

In the summer of 1922 Carter persuaded Carnarvon to allow him to conduct one more campaign in the valley. Starting work earlier than usual Howard Carter opened up the stairway to the tomb of Tutankhamun on 4 November 1922. Carnarvon hurried to Luxor and the tomb was entered on 26 November. The discovery astounded the world: a royal tomb, mostly undisturbed, full of spectacular objects. Carter recruited a team of expert assistants to help him in the clearance of the tomb, and the conservation and recording of its remarkable contents. On 16 February 1923 the

blocking to the burial chamber was removed, to reveal the unplundered body and funerary equipment of the dead king. Unhappily, the death of Lord Carnarvon on 5 April seriously affected the subsequent progress of Carter's work.

In spite of considerable and repeated bureaucratic interference, not easily managed by the short-tempered excavator, work on the clearance of the tomb proceeded slowly, but was not completed until 1932. Carter handled the technical processes of clearance, conservation, and recording with exemplary skill and care. A popular account of the work was published in three volumes, "The Tomb of Tut-ankh-Amen" (1923–33), the first of which was substantially written by his principal assistant, Arthur C. Mace. No archaeological discovery had met with such sustained public interest, yet Carter received no formal honours from his own country.” (DNB).