Correspondence, Notes, and Photographs of Euro-American Settlers of South Dakota Concerning Life and Times in the Dakota Territory c. 1884 and an Incident in the Early Political History of the State of South Dakota c. 1891

- Approximately 242 pieces total. Two hardcover books, both by Frances Wood: Gospel Four Corners, inscribed by Edward Shurtleff; T

- South Dakota; Illinois; New York City; and Englewood, New Jersey , 1933

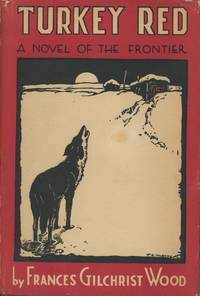

South Dakota; Illinois; New York City; and Englewood, New Jersey, 1933. Approximately 242 pieces total. Two hardcover books, both by Frances Wood: Gospel Four Corners, inscribed by Edward Shurtleff; Turkey Red: A Novel of the Frontier, inscribed by Wood. Sixty-four 8 ½ x 11 inch typed pages; sixty-six 8 ½ x 11 inch handwritten pages; two 8 x 5 inch typed pages; thirty 8 x 5 handwritten pages. Of the written materials, thirty-five pieces date from 1928, one from 1929, two from 1930, ten from 1931, fifty-two from 1932, and sixty-one from 1933. Fifty-six photographs; nine 8 x 11 inches and smaller; twelve 3 ½ x 5 inches and smaller; and thirty-five 2 ½ x 3 ½ inches and smaller; with eight negatives. Of the photographs, thirty-two printed in 1928; the remainder are undated. Fourteen pieces of ephemera. Overall excellent.. Frances Gilchrist Wood (1859–1944) was a reporter, newspaper editor, and author born in Carthage, Illinois. Her father was a civil engineer, and brought Wood and her brother out to what was then the Dakota Territory in 1883. Wood laid claim to a piece of land outside Appomattox Township, near LeBeau, Dakota Territory (now South Dakota); she lived there for two years but never “proved up” on the claim. She would draw heavily on her frontier experiences in her fiction. Edward David Shurtleff (1863–1936) was a lawyer from Genoa, Illinois. An Oberlin College graduate, Shurtleff would live briefly in LeBeau, practice law in the Dakota Territory and in Illinois, and later serve in the Illinois House of Representatives and as an Illinois Circuit Court and Appellate Court judge.

Offered here is an archive of notes and correspondence between Shurtleff and various Euro-American settlers of the Dakota Territory, especially Wood; and Shurtleff’s photographs, including from a trip to see what remained of LeBeau. Also included are letters to Shurtleff from South Dakota state historian Jonah LeRoy “Doane” Robinson (1856–1946) though, surprisingly, these letters concern a political intrigue surrounding the alleged fixing of the 1890–91 Senate elections for Illinois and South Dakota.

Shurtleff mainly corresponded with Doane Robinson in 1928. The two were apparently investigating the “history of the movement which resulted in the elections of Senators Palmer and Kyle” (August 3) – John M. Palmer of Illinois and James H. Kyle of South Dakota. Robinson lays out the story of Kyle’s election, starting with a “suggestion” of “the possibility of a combination by which both Illinois and South Dakota would supply senators opposed to the republicans” (August 3):

“The affair started with Jerry Simpson’s suggestion printed in the Chicago Tribune of February 10" I presume this led to Telegraphic correspondence. On the morning of the 13" Seward left for Chicago and the republicans knew that he had gone to help fix the deal. We knew too on Saturday evening that he had wired that an agreement had been reached. It seems to me that this telegram came from Marengo. Henry Stearns, of Brookings county, elected as a populist had assured us that if his vote would elect Mellette we could have it. It was necessary to get one other populist to defeat the Kyle-Palmer enterprise. We thought we had him lined up and went into the session Monday morning with a good deal of confidence. I forget who the second man was, and of course there is no record by which to check up, but his name came before Stearns in the roll call and he couldnt stand the pressure, and voted for Kyle. That of course released Stearns and put Kyle across.” (July 27)

The plan works; “Monday morning, February 16" Kyle was elected exactly in compliance with the programme” (August 3). Kyle was a Populist, and his election was apparently in exchange for preventing election of a Republican in Illinois:

“I lived in Yankton and was upon familiar terms with Judge Tripp and with [Hughes] East who was Tripp’s major domo in the senatorial campaign and was told by both that the only condition upon which the democratic vote was given to Kyle was that a democratic senator was to be secured from Illinois, and East said the deal was approved by Grover Cleveland and that pursuant to it Tripp was made U.S. Minister to Austria. I have no doubt whatever of the accuracy of this statement, for I have never known a defeated candidate for any office to be so complacent as was Bartlett Tripp over his defeat by Kyle”. (August 3)

Robinson later claims that Cleveland did not just approve the deal, but “was consulted and advised this course” (October 17).

1928 is also when Shurtleff strikes up a correspondence with Frances Wood, writing to her publisher, Collier, for her address. She gives Shurtleff a brief biography, and tells him of her current plans “to find ‘the frontier’ again”:

“—some place that has the feel of it in the air. In the plains it has long ago vanished in farms and roads and crowds. Down in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, I came near it in the mining and mountain grazing country. Now I am going to try Montana and Idaho, with a possible stop in Dakota. I’m after another novel. Do you remember how, with no bolstering family or society behind him, the frontier ‘ripped out every man according to his stitch’? I've run into the same thing down in the jungles in Central and South America where men go black, and the Sahara desert where men go native—everywhere where a man has to stand on his own without support. Equally the quiet law-abiding man back home promptly headed the Vigilance Committee on the border.” (May 6)

In 1930, Wood would get a publishing deal for Turkey Red, a semi-fictional account of the Dakota frontier, and would complete the book in 1931. She tells Shurtleff, “I’m so glad I knew you before I wrote it, for you’ve been the living human being with me in a world of ghosts” (August 22, 1932). In a copy of a letter to newspaperman Ernest Noteboom, Wood discusses the gruesome autobiographical sources of Turkey Red:

“Very little of the novel is pure fiction. The baby with croup was my own. After that storm another lone mother was found in her shack, unconscious from exhaustion and cold, with her baby dead on her knees. And dear old Dan’s mules halted behind Gleason’s shack in the gray of a winter morning, with Dan frozen stiff on the driver’s seat, lines clutched in his dead hands. Ask any of the old-timers if they were liable to forget being lost in a blizzard or fighting prairie fires or being hailed out or camping out all night lost on the prairie with a year old baby—or the wolves howling and coyotes yipping, or dodging rattlers in the buffalo grass, or building a sod house and trying to live in it, fighting hawks or a Durham cow at the other end of a picket rope?” (October 14, 1932)

Noteboom is apparently interested, as Shurtleff writes him a long letter describing his own time in the wilderness . His journey began at the end of March 1884, when he took a train from Watertown to Aberdeen, and then to Ipswich. There he transferred to a stagecoach—the M&StL railway had yet to be built—which took him through Roscoe, Bowdle, and Theodore. Finally, on the third day, he arrived on foot at LeBeau, at “Gus Siebrecht’s three-story hotel”:

“LeBeau then had about six hundred people in the town and scattered up the valley to the northeast. [...] It was a busy, stirring place. [...] Soon after getting to LeBeau I took up a homestead on “Blue Blanket” prairie, about nine miles northeast of LeBeau, a beautiful piece of land, as I could find nothing down around the river. I soon afterward made the acquaintance of Will Younger, who clerked in Cobb's hardware store and who had squatted upon a quarter section about ten miles north on what was called ‘Midnight Bench,’ and I went with him one Saturday and stayed over Sunday with him in his sod dugout. There were three or four other squatters on this unsurveyed tract [...] I could have taken a claim on this Bench, which was not surveyed or opened up for settlement, but no one knew when it ever would be surveyed. I finally concluded to preempt one hundred sixty acres running a mile north and south, the most westerly surveyed land, and about one and one-fourth miles east of the river and about a mile from Younger's dugout. I sent in my papers, procured my receipt and built a second shack on this tract, abandoning the homestead out on the prairie.” (October 22, 1932)

Soon, the government opened the land up for settlement:

“Not a great while after, I was staying all night with Younger at the other place in a large sod house all above ground [...] and in the middle of the night we heard a great hubbub on the prairie, lumber wagons rumbling everywhere, shouting and much noise. We got up and went out and saw wagons and heard calling everywhere. [...] a telegram had come to Peter Couchman, the sheriff, that the tract had been opened for settlement by the Government and would be surveyed soon. [...] The squatters took everything that night not taken, south of the little brook opposite the island which I mentioned before. In the early morning I went up beyond the brook about a quarter of a mile to the first level land on what I now call ‘Mobridge Bench’ and dug out a cellar three feet deep, about twelve by sixteen feet, taking care of the sod, built a sod house and staked out one hundred and sixty acres of land.”

He invites his Watertown friends E.E. Seward and Ed Nickerson out to join him. The spring and summer are promising:

“Indeed, it was a live town in the spring and early summer of 1884. Nearly every day the town was full of Indians who lived up the Moreau River and who came over in boats and traded fish, beads, moccasins, etc., for goods, and one day Chief Gaul, who was with Sitting Bull at the Custer massacre, was there; he lived, I think, up at Fort Yates.”

But the three do not find much success:

“I shall never forget that summer. We all soon ran out of money except Nickerson. [...] After we ran out of money Gus Siebrecht gave us the use of his old log house, which we slept in as long as we stayed in LeBeau. I was Gus’s legal adviser in and about some matters that he considered of grave concern, in the early part of the season. As the summer wore on and Gus commenced to see that the roads were not coming before another year these legal matters also depreciated in importance. He was the weather or railroad sign for the town. If Gus Siebrecht came across the street in the morning with a jolly look on his face it was immediately heralded that the road (railroad) would be into town within three months. As the summer moved along there were not many jolly looks upon his countenance and people commenced to drift away from LeBeau.”

Shurtleff says that when he returned in 1895, “Gus Siebrecht was holding the fort alone.” He seems to have found his time in LeBeau overall difficult, dangerous, and unrewarding: there were “numerous horse thieves that plied their trade between the white man and the Indians back and forth across the river, and made a rendezvous at LeBeau”; and his shack at Midnight Bench was so poor that “as soon as it became dusk [I would] walk a mile and a quarter over to Olsen’s [...] and sleep in his mud plastered log house, with hard mud floor”. He writes that “LeBeau in 1884 [...] was the real border life and nothing about it tended toward stability or uplift.”

This does not prevent him from nostalgia, and his friendship with Wood seems to have inspired Shurtleff to seek out more fellow Dakota settlers to share their stories. Ira O. Curtiss of Aberdeen, South Dakota writes to him that “When I came to Aberdeen the 14th day of May, 1881, there were about 20 people here, with no railroad and only a few sod houses. It just happens that I am the only person in Aberdeen to day that was here the day I came” (September 19, 1932). In 1933 Shurtleff writes to E.B Green, who came to the area a few years after Shurtleff’s time. He tells Shurtleff about a few colorful characters:

“Old man Terres had a ranch on swan creek just in sight of the present town of Lowry. He was said to have quite a reputation as a cattle rustler, though as to the truth of this I cannot vouch for. My cousin had a mortgage on two of his oxen and had to foreclose on him. He put up a fight and threatened to shoot anyone who tried to take his oxen. Sheriff Matt Cowly of Bowdle and a crowd of us went down and arrested him. [...] It was here in 1889 I met and shook hands with old Sitting Bull with whom Peter [Couchman] was well acquainted and anxious to retain his friendship.” (March 30)

Green also remembers incidents of violence between the white and Native populations. He mentions that an Ed Taylor “was shot to death by an Indian at Forest City Mission School”—possibly the residential school near Gettysburg, South Dakota—and asks, “Was it Dode Curler that had a squaw wife and shot her by mistake, near a spring, thinking she was a deer or was it Seebrecht?” (September 7). He reminds Shurtleff of “old one-eyed Phil Du Fran” who was “once guide to General Custer” and “‘Old Tex’ half breed Indian, with long hair” who “was a good natured, harmless old southern soul who promised to advise the Bangorites of any Indian uprising should it occur” (April 7) – Shurtleff remembers Old Tex “with the snakes about his neck” (October 1). Green also recalls a near-deadly prank at a picnic on the Missouri River:

“among the number were Dick Wright –; Tom Amerpohl and Edgar Warner, who in the dusk of the evening – after supper – left our camp + betook themselves to the river for a swim; after which they mounted ponies and naked + bare backed raced up the river hooting + shouting like so many Indians – to near the Jackson residence. It was just before the Indian outbreak when the reds were having this ghost dancer, Jacobsen heard them coming, + believing it was a party of marauding red skins bent on mischief – calmly stationed himself outside near a side window + giving his wife instructions to load the shot gun + hand to him through the open window, he took aim on the foremost rider – + with finger on the trigger – waited till the party should get a little closer Lucky it was for Dick Wright – that Jacobson recognized his voice in the foggy darkness of the evening + refrained from shooting. ‘I was sure it was a party of Indians. Cap said but I was not afraid + had it in my mind just how to proceed to out wit them; when I discovered who they were though I shook + trembled like a leaf for a long time.’” (April 25, 1933)

Also included in the archive are a number of photographs, thirty-two of which are from Shurtleff’s trip to LeBeau in about 1928. Shurtleff described in his letter to Noteboom how interest in LeBeau had waned and its residents had moved away; the photographs—mainly of large, empty fields, with perhaps a solitary building or foundation—bear this out.

Overall, a first-person record of turbulent times on the frontier just prior to and just following South Dakota’s statehood. Of interest especially to scholars of Midwest and South Dakota history, homesteading, and white relations with Native Americans.

Offered here is an archive of notes and correspondence between Shurtleff and various Euro-American settlers of the Dakota Territory, especially Wood; and Shurtleff’s photographs, including from a trip to see what remained of LeBeau. Also included are letters to Shurtleff from South Dakota state historian Jonah LeRoy “Doane” Robinson (1856–1946) though, surprisingly, these letters concern a political intrigue surrounding the alleged fixing of the 1890–91 Senate elections for Illinois and South Dakota.

Shurtleff mainly corresponded with Doane Robinson in 1928. The two were apparently investigating the “history of the movement which resulted in the elections of Senators Palmer and Kyle” (August 3) – John M. Palmer of Illinois and James H. Kyle of South Dakota. Robinson lays out the story of Kyle’s election, starting with a “suggestion” of “the possibility of a combination by which both Illinois and South Dakota would supply senators opposed to the republicans” (August 3):

“The affair started with Jerry Simpson’s suggestion printed in the Chicago Tribune of February 10" I presume this led to Telegraphic correspondence. On the morning of the 13" Seward left for Chicago and the republicans knew that he had gone to help fix the deal. We knew too on Saturday evening that he had wired that an agreement had been reached. It seems to me that this telegram came from Marengo. Henry Stearns, of Brookings county, elected as a populist had assured us that if his vote would elect Mellette we could have it. It was necessary to get one other populist to defeat the Kyle-Palmer enterprise. We thought we had him lined up and went into the session Monday morning with a good deal of confidence. I forget who the second man was, and of course there is no record by which to check up, but his name came before Stearns in the roll call and he couldnt stand the pressure, and voted for Kyle. That of course released Stearns and put Kyle across.” (July 27)

The plan works; “Monday morning, February 16" Kyle was elected exactly in compliance with the programme” (August 3). Kyle was a Populist, and his election was apparently in exchange for preventing election of a Republican in Illinois:

“I lived in Yankton and was upon familiar terms with Judge Tripp and with [Hughes] East who was Tripp’s major domo in the senatorial campaign and was told by both that the only condition upon which the democratic vote was given to Kyle was that a democratic senator was to be secured from Illinois, and East said the deal was approved by Grover Cleveland and that pursuant to it Tripp was made U.S. Minister to Austria. I have no doubt whatever of the accuracy of this statement, for I have never known a defeated candidate for any office to be so complacent as was Bartlett Tripp over his defeat by Kyle”. (August 3)

Robinson later claims that Cleveland did not just approve the deal, but “was consulted and advised this course” (October 17).

1928 is also when Shurtleff strikes up a correspondence with Frances Wood, writing to her publisher, Collier, for her address. She gives Shurtleff a brief biography, and tells him of her current plans “to find ‘the frontier’ again”:

“—some place that has the feel of it in the air. In the plains it has long ago vanished in farms and roads and crowds. Down in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, I came near it in the mining and mountain grazing country. Now I am going to try Montana and Idaho, with a possible stop in Dakota. I’m after another novel. Do you remember how, with no bolstering family or society behind him, the frontier ‘ripped out every man according to his stitch’? I've run into the same thing down in the jungles in Central and South America where men go black, and the Sahara desert where men go native—everywhere where a man has to stand on his own without support. Equally the quiet law-abiding man back home promptly headed the Vigilance Committee on the border.” (May 6)

In 1930, Wood would get a publishing deal for Turkey Red, a semi-fictional account of the Dakota frontier, and would complete the book in 1931. She tells Shurtleff, “I’m so glad I knew you before I wrote it, for you’ve been the living human being with me in a world of ghosts” (August 22, 1932). In a copy of a letter to newspaperman Ernest Noteboom, Wood discusses the gruesome autobiographical sources of Turkey Red:

“Very little of the novel is pure fiction. The baby with croup was my own. After that storm another lone mother was found in her shack, unconscious from exhaustion and cold, with her baby dead on her knees. And dear old Dan’s mules halted behind Gleason’s shack in the gray of a winter morning, with Dan frozen stiff on the driver’s seat, lines clutched in his dead hands. Ask any of the old-timers if they were liable to forget being lost in a blizzard or fighting prairie fires or being hailed out or camping out all night lost on the prairie with a year old baby—or the wolves howling and coyotes yipping, or dodging rattlers in the buffalo grass, or building a sod house and trying to live in it, fighting hawks or a Durham cow at the other end of a picket rope?” (October 14, 1932)

Noteboom is apparently interested, as Shurtleff writes him a long letter describing his own time in the wilderness . His journey began at the end of March 1884, when he took a train from Watertown to Aberdeen, and then to Ipswich. There he transferred to a stagecoach—the M&StL railway had yet to be built—which took him through Roscoe, Bowdle, and Theodore. Finally, on the third day, he arrived on foot at LeBeau, at “Gus Siebrecht’s three-story hotel”:

“LeBeau then had about six hundred people in the town and scattered up the valley to the northeast. [...] It was a busy, stirring place. [...] Soon after getting to LeBeau I took up a homestead on “Blue Blanket” prairie, about nine miles northeast of LeBeau, a beautiful piece of land, as I could find nothing down around the river. I soon afterward made the acquaintance of Will Younger, who clerked in Cobb's hardware store and who had squatted upon a quarter section about ten miles north on what was called ‘Midnight Bench,’ and I went with him one Saturday and stayed over Sunday with him in his sod dugout. There were three or four other squatters on this unsurveyed tract [...] I could have taken a claim on this Bench, which was not surveyed or opened up for settlement, but no one knew when it ever would be surveyed. I finally concluded to preempt one hundred sixty acres running a mile north and south, the most westerly surveyed land, and about one and one-fourth miles east of the river and about a mile from Younger's dugout. I sent in my papers, procured my receipt and built a second shack on this tract, abandoning the homestead out on the prairie.” (October 22, 1932)

Soon, the government opened the land up for settlement:

“Not a great while after, I was staying all night with Younger at the other place in a large sod house all above ground [...] and in the middle of the night we heard a great hubbub on the prairie, lumber wagons rumbling everywhere, shouting and much noise. We got up and went out and saw wagons and heard calling everywhere. [...] a telegram had come to Peter Couchman, the sheriff, that the tract had been opened for settlement by the Government and would be surveyed soon. [...] The squatters took everything that night not taken, south of the little brook opposite the island which I mentioned before. In the early morning I went up beyond the brook about a quarter of a mile to the first level land on what I now call ‘Mobridge Bench’ and dug out a cellar three feet deep, about twelve by sixteen feet, taking care of the sod, built a sod house and staked out one hundred and sixty acres of land.”

He invites his Watertown friends E.E. Seward and Ed Nickerson out to join him. The spring and summer are promising:

“Indeed, it was a live town in the spring and early summer of 1884. Nearly every day the town was full of Indians who lived up the Moreau River and who came over in boats and traded fish, beads, moccasins, etc., for goods, and one day Chief Gaul, who was with Sitting Bull at the Custer massacre, was there; he lived, I think, up at Fort Yates.”

But the three do not find much success:

“I shall never forget that summer. We all soon ran out of money except Nickerson. [...] After we ran out of money Gus Siebrecht gave us the use of his old log house, which we slept in as long as we stayed in LeBeau. I was Gus’s legal adviser in and about some matters that he considered of grave concern, in the early part of the season. As the summer wore on and Gus commenced to see that the roads were not coming before another year these legal matters also depreciated in importance. He was the weather or railroad sign for the town. If Gus Siebrecht came across the street in the morning with a jolly look on his face it was immediately heralded that the road (railroad) would be into town within three months. As the summer moved along there were not many jolly looks upon his countenance and people commenced to drift away from LeBeau.”

Shurtleff says that when he returned in 1895, “Gus Siebrecht was holding the fort alone.” He seems to have found his time in LeBeau overall difficult, dangerous, and unrewarding: there were “numerous horse thieves that plied their trade between the white man and the Indians back and forth across the river, and made a rendezvous at LeBeau”; and his shack at Midnight Bench was so poor that “as soon as it became dusk [I would] walk a mile and a quarter over to Olsen’s [...] and sleep in his mud plastered log house, with hard mud floor”. He writes that “LeBeau in 1884 [...] was the real border life and nothing about it tended toward stability or uplift.”

This does not prevent him from nostalgia, and his friendship with Wood seems to have inspired Shurtleff to seek out more fellow Dakota settlers to share their stories. Ira O. Curtiss of Aberdeen, South Dakota writes to him that “When I came to Aberdeen the 14th day of May, 1881, there were about 20 people here, with no railroad and only a few sod houses. It just happens that I am the only person in Aberdeen to day that was here the day I came” (September 19, 1932). In 1933 Shurtleff writes to E.B Green, who came to the area a few years after Shurtleff’s time. He tells Shurtleff about a few colorful characters:

“Old man Terres had a ranch on swan creek just in sight of the present town of Lowry. He was said to have quite a reputation as a cattle rustler, though as to the truth of this I cannot vouch for. My cousin had a mortgage on two of his oxen and had to foreclose on him. He put up a fight and threatened to shoot anyone who tried to take his oxen. Sheriff Matt Cowly of Bowdle and a crowd of us went down and arrested him. [...] It was here in 1889 I met and shook hands with old Sitting Bull with whom Peter [Couchman] was well acquainted and anxious to retain his friendship.” (March 30)

Green also remembers incidents of violence between the white and Native populations. He mentions that an Ed Taylor “was shot to death by an Indian at Forest City Mission School”—possibly the residential school near Gettysburg, South Dakota—and asks, “Was it Dode Curler that had a squaw wife and shot her by mistake, near a spring, thinking she was a deer or was it Seebrecht?” (September 7). He reminds Shurtleff of “old one-eyed Phil Du Fran” who was “once guide to General Custer” and “‘Old Tex’ half breed Indian, with long hair” who “was a good natured, harmless old southern soul who promised to advise the Bangorites of any Indian uprising should it occur” (April 7) – Shurtleff remembers Old Tex “with the snakes about his neck” (October 1). Green also recalls a near-deadly prank at a picnic on the Missouri River:

“among the number were Dick Wright –; Tom Amerpohl and Edgar Warner, who in the dusk of the evening – after supper – left our camp + betook themselves to the river for a swim; after which they mounted ponies and naked + bare backed raced up the river hooting + shouting like so many Indians – to near the Jackson residence. It was just before the Indian outbreak when the reds were having this ghost dancer, Jacobsen heard them coming, + believing it was a party of marauding red skins bent on mischief – calmly stationed himself outside near a side window + giving his wife instructions to load the shot gun + hand to him through the open window, he took aim on the foremost rider – + with finger on the trigger – waited till the party should get a little closer Lucky it was for Dick Wright – that Jacobson recognized his voice in the foggy darkness of the evening + refrained from shooting. ‘I was sure it was a party of Indians. Cap said but I was not afraid + had it in my mind just how to proceed to out wit them; when I discovered who they were though I shook + trembled like a leaf for a long time.’” (April 25, 1933)

Also included in the archive are a number of photographs, thirty-two of which are from Shurtleff’s trip to LeBeau in about 1928. Shurtleff described in his letter to Noteboom how interest in LeBeau had waned and its residents had moved away; the photographs—mainly of large, empty fields, with perhaps a solitary building or foundation—bear this out.

Overall, a first-person record of turbulent times on the frontier just prior to and just following South Dakota’s statehood. Of interest especially to scholars of Midwest and South Dakota history, homesteading, and white relations with Native Americans.