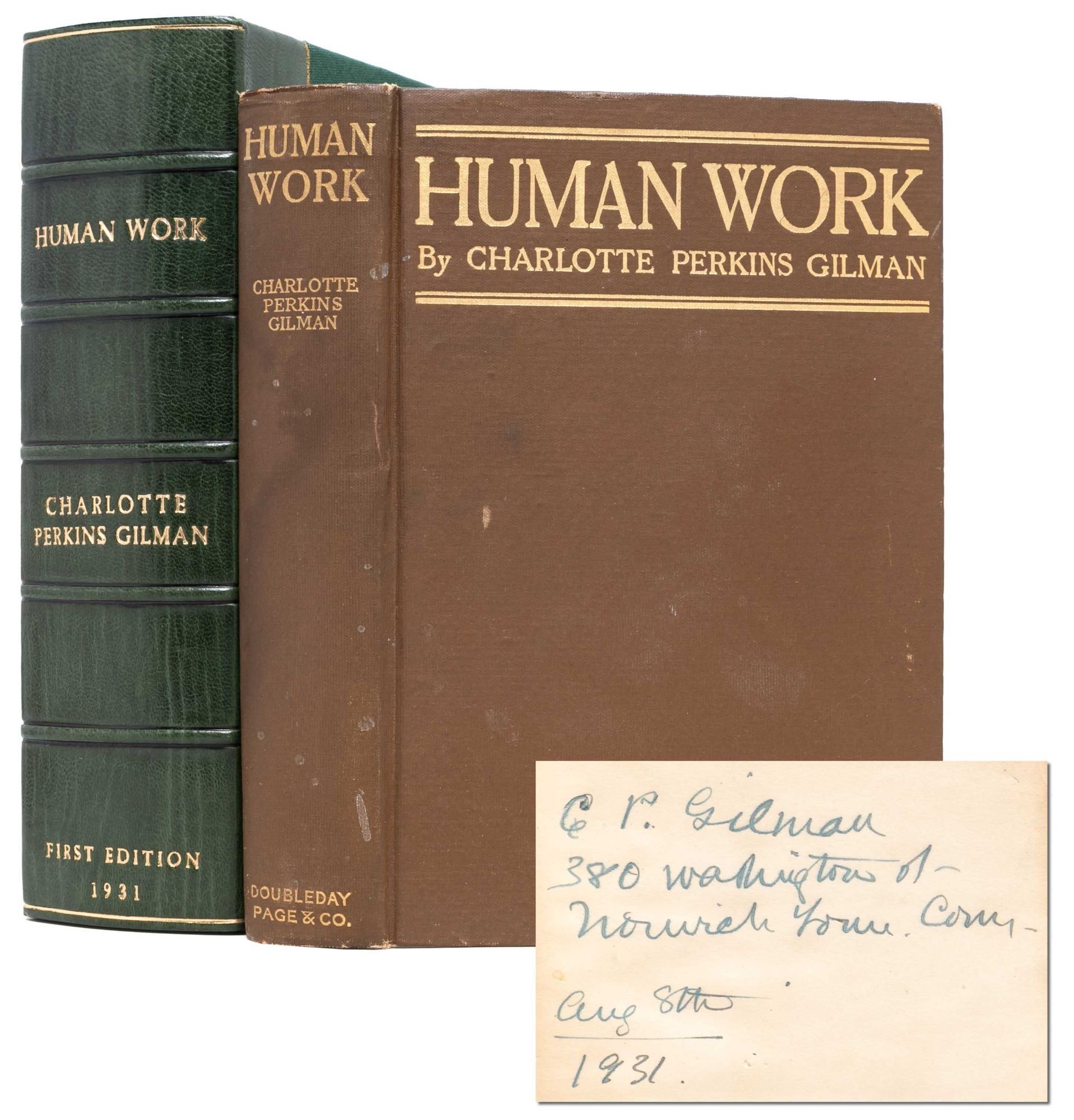

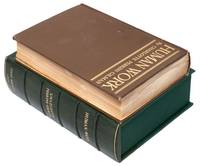

Human Work (the Author's copy)

- New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1904

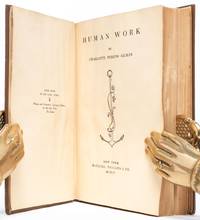

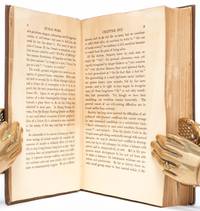

New York: McClure, Phillips & Co, 1904. First edition. Very Good. With the ownership signature of Charlotte Perkins Gilman ("C.P. Gilman"), her address (380 Washington St in Norwich, Connecticut, where she and her husband Houghton Gilman lived from 1922 to 1934), and the date ("Aug 8th 1931") in ink to front flyleaf. Octavo. Publisher's brown cloth titled in gilt. Inner hinges expertly closed. Some dampstaining, causing a few blemishes to cloth and some wrinkling to leaves in first half of the book. Still a Very Good example of an important book by one of America's leading women's rights activists, this copy having belonged to the author herself. Housed in a custom green quarter morocco case.

In her introduction to this groundbreaking analysis on the relationship between economics and gender, Gilman (1860 - 1935) writes, "This book is a study of the economic processes of society, explaining the immediate causes of a large part of our human suffering, and suggesting certain simple, swift, and easy changes of mind by which we may so alter our processes so as to avoid that suffering and promote our growth and happiness." Maintaining that women carried equal intellectual capacity to men, she argues in Human Work that it is the "sexuo-economic oppression of women" and not biological inferiority that prevented women from participating in (and profiting from) certain types of work. "Accusing men of appropriating certain work as 'men's work' and masking the process as a biological locus rather than an exercise in power relations, Gilman asserts that men created an economic dependence that has prevented women from success in the workplace" (Kimmel & Moynihan). From this inequity, Gilman argues, springs suffering not only for women but for their families and society at large. Ultimately, the best course for improving overall social conditions is addressing the systemic sexual-economic inequities that hold women back from both contributing work to the community and benefiting from that work.

Still considered one of the most important feminists of her day, Gilman was an ardent suffragist and advocate for women's rights to property, equal employment, and bodily autonomy. Gilman also broke ground as an author: her short story "The Yellow Wallpaper" (1892), inspired by her own experiences with postpartum depression, remains an iconic example of both feminist literature and psychological horror; similarly, her utopian novel Herland (first serialized in Gilman's feminist periodical The Forerunner) is a pioneering work of feminist speculative fiction. Gilman was also a prolific author on social science topics; Human Work explores many of the themes she began to develop in her earlier work Women and Economics (1898).

Kimmel & Moynihan, introduction to the Altamira Press edition of Human Work (2005). Very Good.

In her introduction to this groundbreaking analysis on the relationship between economics and gender, Gilman (1860 - 1935) writes, "This book is a study of the economic processes of society, explaining the immediate causes of a large part of our human suffering, and suggesting certain simple, swift, and easy changes of mind by which we may so alter our processes so as to avoid that suffering and promote our growth and happiness." Maintaining that women carried equal intellectual capacity to men, she argues in Human Work that it is the "sexuo-economic oppression of women" and not biological inferiority that prevented women from participating in (and profiting from) certain types of work. "Accusing men of appropriating certain work as 'men's work' and masking the process as a biological locus rather than an exercise in power relations, Gilman asserts that men created an economic dependence that has prevented women from success in the workplace" (Kimmel & Moynihan). From this inequity, Gilman argues, springs suffering not only for women but for their families and society at large. Ultimately, the best course for improving overall social conditions is addressing the systemic sexual-economic inequities that hold women back from both contributing work to the community and benefiting from that work.

Still considered one of the most important feminists of her day, Gilman was an ardent suffragist and advocate for women's rights to property, equal employment, and bodily autonomy. Gilman also broke ground as an author: her short story "The Yellow Wallpaper" (1892), inspired by her own experiences with postpartum depression, remains an iconic example of both feminist literature and psychological horror; similarly, her utopian novel Herland (first serialized in Gilman's feminist periodical The Forerunner) is a pioneering work of feminist speculative fiction. Gilman was also a prolific author on social science topics; Human Work explores many of the themes she began to develop in her earlier work Women and Economics (1898).

Kimmel & Moynihan, introduction to the Altamira Press edition of Human Work (2005). Very Good.