MALMANTILE RACQUISTATO POEMA DI PERLONE ZIPOLI FIORENTINO [Early Manuscript Copy]

- Hardcover

- [n.p.]: [n.p], [c. 1675]

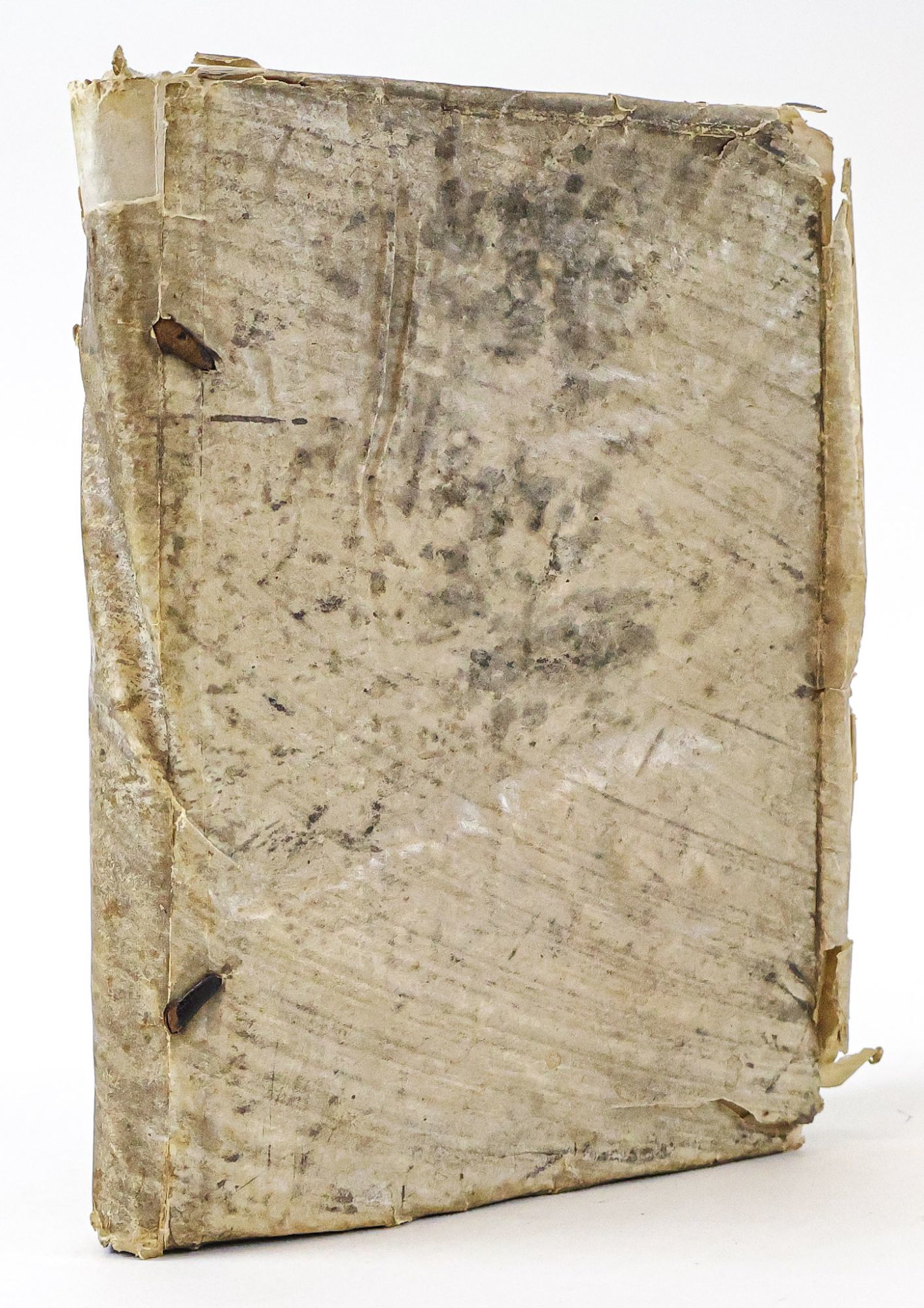

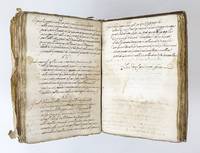

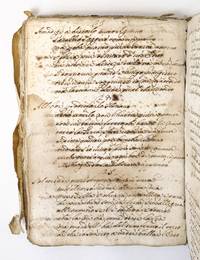

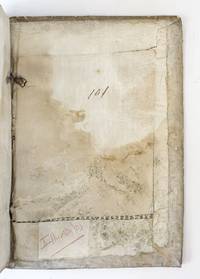

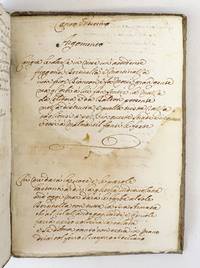

[n.p.]: [n.p], [c. 1675]. Hardcover. Octavo, [324 pages]. In Good condition. Bound in full contemporary vellum ("boards" composed of multiple sheets of 17th-century sheets. Vellum is beginning to separate from composite-sheet boards along fore-edges. Boards have moderate plus staining overall, with moderate plus chipping and wear to vellum along edges. Textblock shows moderate age toning and light wear to untrimmed edges, with occasional light staining to pages (not impacting legibility. Undated ink manuscript in an unidentified 17th-century Italian hand. Shelved Room A.

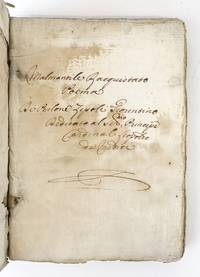

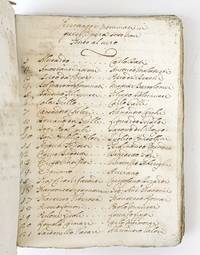

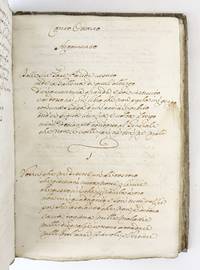

An early handwritten manuscript of Lippi's Il Malmantile Racquistato, which appears to predate the second printed edition in 1688 (and possibly the first printed edition in 1676). The present manuscript differs from one or both of the 17th-century editions in multiple points (please see notes for further analysis of contrast with the published manuscript tradition of the text). Title page includes a dedication to Cardinal Leopoldo de Medici (lacking in the first printed edition), and attributes the work to Lippi's pseudonym Perlone Zipoli - unlike both 17th-century editions. The title page is followed by the prefatory Disfatto, here attributed to the anagrammatic pseudonym Amostante Latoni (Antonio Malatesti). The work is then prefaced by an index revealing the "true identities" of all the figures appearing pseudonymously in the work. Contrary to both printed editions, each book is here referred to as canto rather than cantare, and each stanza is numbered (similarly to the 1688 edition, and unlike the 1676 edition). Shelved Room A. The mock-heroic epic Malmantile Racquistato was written by Florentine painter Lorenzo Lippi (1606–1665) during the 1640s. Writing under the anagrammatic pseudonym Perlone Zipoli, Lippi composed the poem while serving Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici and his wife at Innsbruck. Il Malmantile is often read as a parodic response to contemporary literary conventions, particularly the epic stylings of Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata. Yet beyond its burlesque tone, the work serves as a celebration of the Tuscan—specifically Florentine—dialect, and is still studied today as a rich repository of regional idioms and turns of phrase.

While the core of the poem was composed in Innsbruck between 1643 and 1644, reports from Lippi’s contemporaries, many of whom were members of the informal literary academy degli Apatisti, suggest that substantial additions and refinements were made after his return to Florence in 1648. Lippi, wary of scandal or public backlash, resisted calls to publish the poem during his lifetime. Nonetheless, it circulated widely among members of the Apatisti, the Accademia degli Svogliati, and even the Accademia della Crusca.

It was not published until 1676, eleven years after Lippi’s death, in a flawed and limited edition (only 50 copies) issued by Giovanni Rossi. That edition was viewed by Lippi’s admirers as a distorted presentation of the poem—possibly even an act of literary revenge. A more authoritative version was published in 1688 under the editorial guidance of Paolo Minucci and the posthumous patronage of Leopoldo de’ Medici.

The present manuscript appears to have been produced prior to the 1688 edition, but after the completion of the poem before Lippi’s death in 1665. Based on textual evidence, it is unlikely to have been copied from either printed edition. Instead, it likely reflects a version circulating independently—perhaps within Lippi’s literary circle or among manuscript readers close to the Medici court. Several features underscore the manuscript’s significance as a witness to the early textual transmission of Malmantile Racquistato. Please note that this list is not comprehensive or exhaustive.

Dedication to Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici (1617-1675)

The manuscript bears a dedication “al Serenissimo Princeps Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici”—a form appropriate only during Leopoldo’s lifetime.

The 1676 edition includes no dedication.

The 1688 edition dedicates the work “alla gloriosa memoria” of the deceased cardinal.

This places the present manuscript’s source text prior to Leopoldo’s death in 1675, supporting an early dating.

Attribution of the “Malmantile Disfatto Enigma”

The manuscript attributes the poem’s enigma to Latoni, a fictional character in the narrative and anagram of Antonio Maltesti (author of the argomentos). The enigma in the present manuscript follows the 1688 edition’s title: “Malmantile Disfatto Enigma” (as opposed to the 1676 edition, which title it simply the “Malmantile Disfatto”).

Unlike the present manuscript, both printed editions attribute the Disfatto to Malatesti, friend of Lippi and author of the the argomentos prefacing each canto/cantare.

Lexical Variant in the Enigma’s First Line

The manuscript and the 1676 edition share the rare form inospite (inhospitable), whereas the 1688 edition substitutes the more conventional indomite (untamed).

The retention of inospite aligns the manuscript with the earlier textual variants, prior to normalization.

Dialectal Verb Form: “dalli” vs. “dagli”

The manuscript occasionally makes use of the form dalli, a dialectal or colloquial variant of dagli.

This reflects non-standard or pre-Cruscan orthography, and suggests a version of the poem less filtered by formal editorial revision.

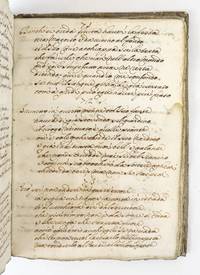

“Canto” vs. “Cantare”

The manuscript titles the poem’s sections as “Cantos”, contrasting with the “Cantare” found in both printed editions.

While “Cantare” evokes the popular cantari tradition, the manuscript’s use of “Canto” suggests either scribal normalization or an attempt to frame the work more in line with classical epic conventions.

Book Seven, Stanza 73

The present manuscript lacks the seventy-third stanza of the seventh canto/cantare, which appears in both the 1676 and 1688 editions.

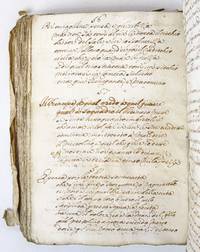

Various Textual Differences, including:

The Argomento of the eighth canto/cantare: Lines 2-5 of the present manuscript have elements that appear to be either hybrids of the two printed editions, or are unique to the manuscript.

Line 2 matches the second edition of 1688

Line 3 matches the first edition of 1676

Line 4 is a unique rendering, more closely aligned with the 1676 edition

Line 5 matches the first edition of 1676

Book 7, Stanza 104 [105 of the printed editions] has, in distinction to both print editions, burlando for brillando.

. 1398897. Special Collections.

An early handwritten manuscript of Lippi's Il Malmantile Racquistato, which appears to predate the second printed edition in 1688 (and possibly the first printed edition in 1676). The present manuscript differs from one or both of the 17th-century editions in multiple points (please see notes for further analysis of contrast with the published manuscript tradition of the text). Title page includes a dedication to Cardinal Leopoldo de Medici (lacking in the first printed edition), and attributes the work to Lippi's pseudonym Perlone Zipoli - unlike both 17th-century editions. The title page is followed by the prefatory Disfatto, here attributed to the anagrammatic pseudonym Amostante Latoni (Antonio Malatesti). The work is then prefaced by an index revealing the "true identities" of all the figures appearing pseudonymously in the work. Contrary to both printed editions, each book is here referred to as canto rather than cantare, and each stanza is numbered (similarly to the 1688 edition, and unlike the 1676 edition). Shelved Room A. The mock-heroic epic Malmantile Racquistato was written by Florentine painter Lorenzo Lippi (1606–1665) during the 1640s. Writing under the anagrammatic pseudonym Perlone Zipoli, Lippi composed the poem while serving Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici and his wife at Innsbruck. Il Malmantile is often read as a parodic response to contemporary literary conventions, particularly the epic stylings of Tasso’s Gerusalemme Liberata. Yet beyond its burlesque tone, the work serves as a celebration of the Tuscan—specifically Florentine—dialect, and is still studied today as a rich repository of regional idioms and turns of phrase.

While the core of the poem was composed in Innsbruck between 1643 and 1644, reports from Lippi’s contemporaries, many of whom were members of the informal literary academy degli Apatisti, suggest that substantial additions and refinements were made after his return to Florence in 1648. Lippi, wary of scandal or public backlash, resisted calls to publish the poem during his lifetime. Nonetheless, it circulated widely among members of the Apatisti, the Accademia degli Svogliati, and even the Accademia della Crusca.

It was not published until 1676, eleven years after Lippi’s death, in a flawed and limited edition (only 50 copies) issued by Giovanni Rossi. That edition was viewed by Lippi’s admirers as a distorted presentation of the poem—possibly even an act of literary revenge. A more authoritative version was published in 1688 under the editorial guidance of Paolo Minucci and the posthumous patronage of Leopoldo de’ Medici.

The present manuscript appears to have been produced prior to the 1688 edition, but after the completion of the poem before Lippi’s death in 1665. Based on textual evidence, it is unlikely to have been copied from either printed edition. Instead, it likely reflects a version circulating independently—perhaps within Lippi’s literary circle or among manuscript readers close to the Medici court. Several features underscore the manuscript’s significance as a witness to the early textual transmission of Malmantile Racquistato. Please note that this list is not comprehensive or exhaustive.

Dedication to Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici (1617-1675)

The manuscript bears a dedication “al Serenissimo Princeps Cardinal Leopoldo de’ Medici”—a form appropriate only during Leopoldo’s lifetime.

The 1676 edition includes no dedication.

The 1688 edition dedicates the work “alla gloriosa memoria” of the deceased cardinal.

This places the present manuscript’s source text prior to Leopoldo’s death in 1675, supporting an early dating.

Attribution of the “Malmantile Disfatto Enigma”

The manuscript attributes the poem’s enigma to Latoni, a fictional character in the narrative and anagram of Antonio Maltesti (author of the argomentos). The enigma in the present manuscript follows the 1688 edition’s title: “Malmantile Disfatto Enigma” (as opposed to the 1676 edition, which title it simply the “Malmantile Disfatto”).

Unlike the present manuscript, both printed editions attribute the Disfatto to Malatesti, friend of Lippi and author of the the argomentos prefacing each canto/cantare.

Lexical Variant in the Enigma’s First Line

The manuscript and the 1676 edition share the rare form inospite (inhospitable), whereas the 1688 edition substitutes the more conventional indomite (untamed).

The retention of inospite aligns the manuscript with the earlier textual variants, prior to normalization.

Dialectal Verb Form: “dalli” vs. “dagli”

The manuscript occasionally makes use of the form dalli, a dialectal or colloquial variant of dagli.

This reflects non-standard or pre-Cruscan orthography, and suggests a version of the poem less filtered by formal editorial revision.

“Canto” vs. “Cantare”

The manuscript titles the poem’s sections as “Cantos”, contrasting with the “Cantare” found in both printed editions.

While “Cantare” evokes the popular cantari tradition, the manuscript’s use of “Canto” suggests either scribal normalization or an attempt to frame the work more in line with classical epic conventions.

Book Seven, Stanza 73

The present manuscript lacks the seventy-third stanza of the seventh canto/cantare, which appears in both the 1676 and 1688 editions.

Various Textual Differences, including:

The Argomento of the eighth canto/cantare: Lines 2-5 of the present manuscript have elements that appear to be either hybrids of the two printed editions, or are unique to the manuscript.

Line 2 matches the second edition of 1688

Line 3 matches the first edition of 1676

Line 4 is a unique rendering, more closely aligned with the 1676 edition

Line 5 matches the first edition of 1676

Book 7, Stanza 104 [105 of the printed editions] has, in distinction to both print editions, burlando for brillando.

. 1398897. Special Collections.