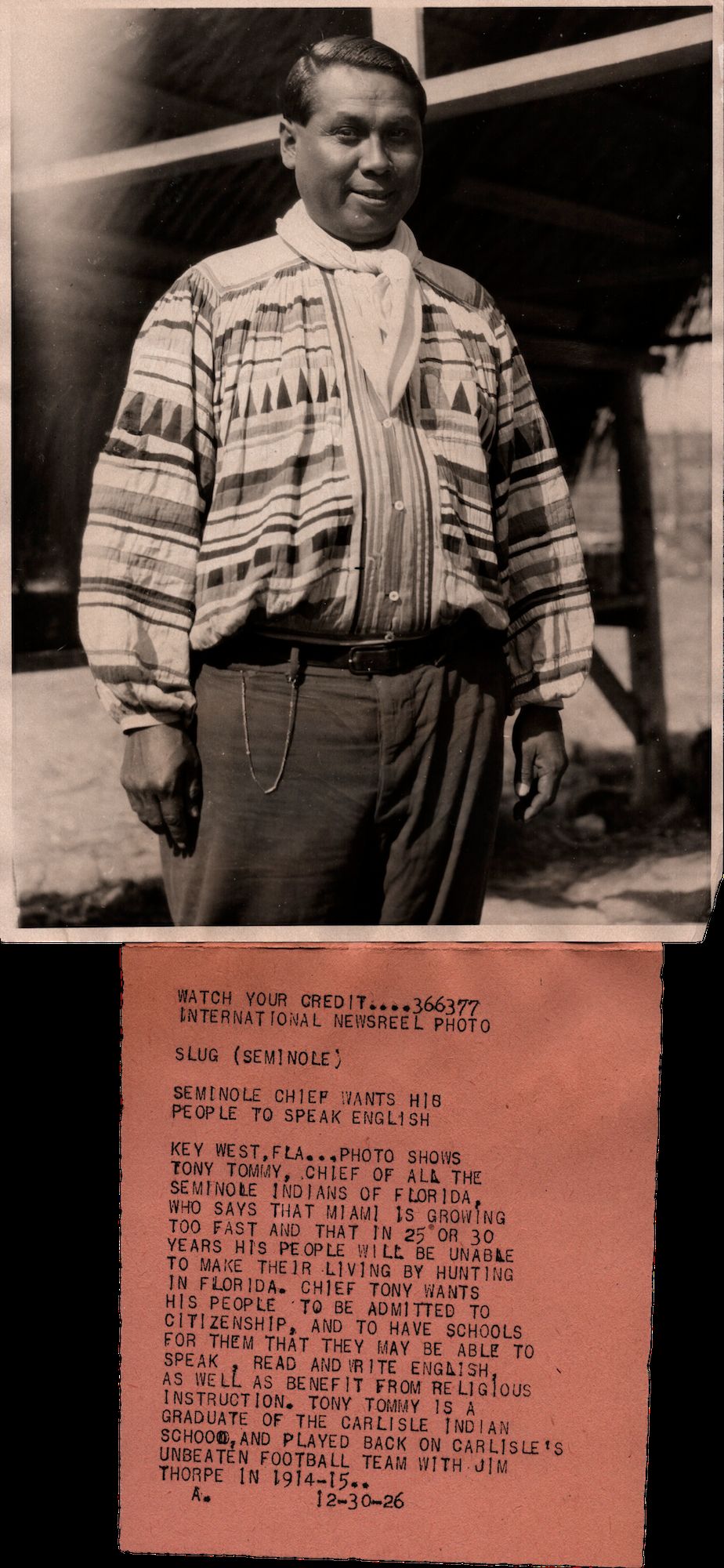

Four 1920s Press Photographs With Captions of Controversial Seminole “Chief” Tony Tommie

- Four photographs, three measuring 6 ½ x 8 ½ inches and one measuring 5 x 7 inches. All with typed captions affixed to bottom.

- Ft. Lauderdale, Key West, and Miami, Florida , 1926

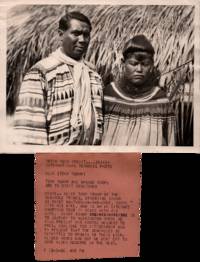

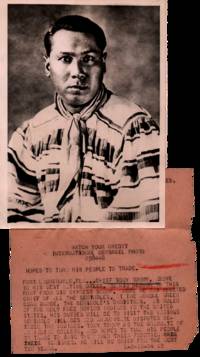

Ft. Lauderdale, Key West, and Miami, Florida, 1926. Four photographs, three measuring 6 ½ x 8 ½ inches and one measuring 5 x 7 inches. All with typed captions affixed to bottom. “International Newsreel” stamps and date stamps with some manuscript captions verso. Some wear and tear to captions; excellent.. Four press photographs, with lengthy captions, of Tony Tommie (c. 1899–1931) in traditional Seminole dress: two individual portraits and two with Edna John, who may or may not have been his wife. The captions describe Tommie (here spelled “Tommy”) as “Chief of all the Seminole Indians of Florida” and “ruler of the only free roving Indians in the United States”, who would “be Chief for the next ten years.” They describe his plans for bringing American education, citizenship, and religious instruction to “his people”.

Tony Tommie himself had such an education; he was the second Seminole to attend an American school, and his student file from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania is readily available. This was controversial among the Florida Seminole at the time. After most had been forcibly relocated following the Seminole Wars, the small number remaining had generally isolated themselves from Euro-American settlers except for occasional trade. Moreover, Tony Tommie was never a chief, as the Seminole did not have chiefs at this time.[1] His trip to Washington, D.C., to “present his formal request to Pres. Coolidge for citizenship”—which a contemporaneous newspaper article described as “Chief Tony Tommy and his braves” “proferr[ing] the pipe of peace” after “more than a century of resistance to the white man”[2]—was undertaken entirely without the knowledge of the tribe’s actual leadership. They were decidedly unhappy with Tommie’s styling himself as chief, and censured him in 1927.[1]

Of interest to historians of southern Florida and the Seminole Tribe of Florida, especially as they began to establish relations with the governments of the US and Florida.

[1] Patsy West, “Controversial ‘Chief’,” The Seminole Tribune, April 14, 2000, 3.

[2] Steuart M. Emery, “Seminole Tribe Offers a Tardy Pipe of Peace,” The New York Times, December 5, 1926, 10.

Tony Tommie himself had such an education; he was the second Seminole to attend an American school, and his student file from the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania is readily available. This was controversial among the Florida Seminole at the time. After most had been forcibly relocated following the Seminole Wars, the small number remaining had generally isolated themselves from Euro-American settlers except for occasional trade. Moreover, Tony Tommie was never a chief, as the Seminole did not have chiefs at this time.[1] His trip to Washington, D.C., to “present his formal request to Pres. Coolidge for citizenship”—which a contemporaneous newspaper article described as “Chief Tony Tommy and his braves” “proferr[ing] the pipe of peace” after “more than a century of resistance to the white man”[2]—was undertaken entirely without the knowledge of the tribe’s actual leadership. They were decidedly unhappy with Tommie’s styling himself as chief, and censured him in 1927.[1]

Of interest to historians of southern Florida and the Seminole Tribe of Florida, especially as they began to establish relations with the governments of the US and Florida.

[1] Patsy West, “Controversial ‘Chief’,” The Seminole Tribune, April 14, 2000, 3.

[2] Steuart M. Emery, “Seminole Tribe Offers a Tardy Pipe of Peace,” The New York Times, December 5, 1926, 10.