Two Letters to Brown, Benson, & Ives Concerning Madeira Imports, Other Goods, and the 1794 Embargo

- Two letters: one three-page letter measuring 7 ½ x 9 inches, folded with tear at seal, else fine; one three-page letter measuri

- New York City , 1794

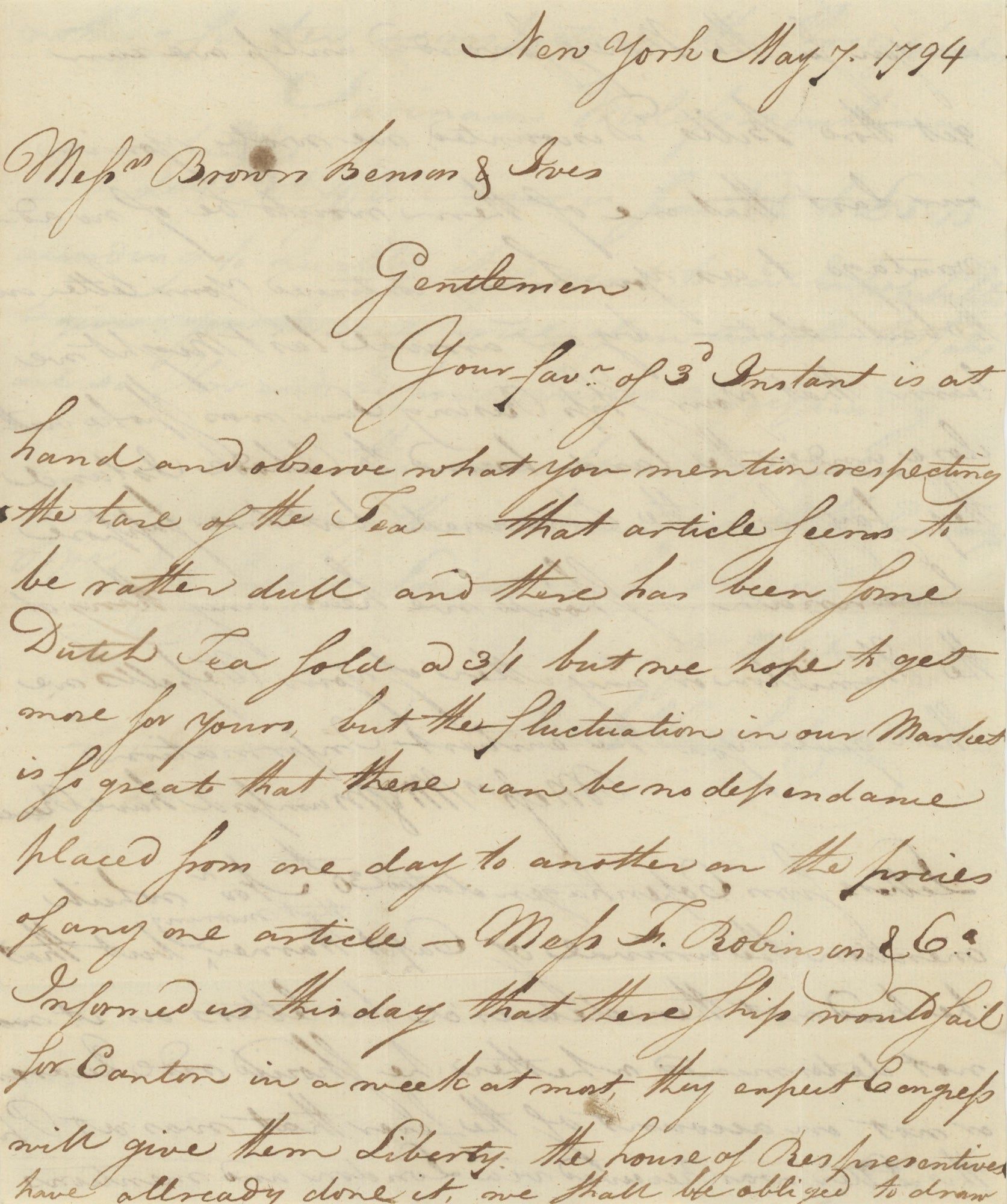

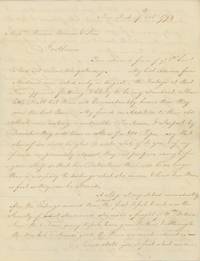

New York City, 1794. Two letters: one three-page letter measuring 7 ½ x 9 inches, folded with tear at seal, else fine; one three-page letter measuring 7 ¾ x 9 ¾ inches, folded with very small tears at some folds, else fine. Overall fine.. Brown, Benson, & Ives was a Rhode Island-based firm founded by Nicholas Brown, Jr. (1769–1841), George Benson (1752–1836), and Thomas Poynton Ives (1769–1835).[1] Benson and Ives were merchants; Brown was a merchant and the namesake of Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. The letters are from “Jos” (Joseph) Green and Nicholas Cooke & Co. The signature on the latter does not appear to belong to the slaver and Rhode Island governor, though the letter could have been written on his behalf by an employee of his company, as it is signed “Nicholas Cooke & Co.”

This company, writing in May, discusses the “dull” taste of recent tea imports and a captain quarantining due to fever, and relays some information about Brown, Benson, & Ives’ ships as well as those of some other companies. In particular, they write that “F. Robinson & Co. informed us this day that their ship would sail for Canton in a week at most, they expect Congress will give them liberty, the House of Representatives have already done it”. This ship likely required Congressional approval because of the embargo, passed in March of that year, on ships going from the US to any foreign port.[2] This embargo was passed in response to British ships capturing American ones in the West Indies to interrupt trade with France, as the two were then engaged in the French Revolutionary Wars. Cooke & Co. inform the firm that “there can be nothing certain learnt respecting the continuation of the embargo. Mr. Jay sails for London on Sunday next.” They are probably referring to John Jay, who in 1794 negotiated a treaty between the US and Britain that relieved some of the post-war tension between the countries.

The later letter comes from Joseph Green (who notes having dispatched a ship “immediately after the Embargo”). Besides providing the prices his company would pay for various articles Brown and company had inquired about, Green’s main concern is madeira, a type of wine produced on the eponymous Portuguese island colony. Green describes that year’s vintage as “flattering, and likely to be very abundant”, and anticipates that prices “will be considerably lower than they were the last year”, although “the market continues good”. Madeira was extremely popular in Colonial America; it was famously involved in the 1768 Liberty affair, in which John Hancock was accused of smuggling the wine on his ship Liberty to avoid import taxes, and which led fairly directly to the Boston Massacre. Following the Revolutionary War, Congress had, ironically, passed a series of higher and higher import taxes on items including madeira wine.

Of interest to scholars of mercantile history early in the US’s statehood, and of the rich and powerful families of Rhode Island.

[1] James B. Hedges, “The Brown Papers: The Record of a Rhode Island Business Family”, American Antiquarian Society, April 1941, 21–36.

[2] Jerald A. Combs, The Jay Treaty, Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers (University of California Press, 1970), 120–121.

This company, writing in May, discusses the “dull” taste of recent tea imports and a captain quarantining due to fever, and relays some information about Brown, Benson, & Ives’ ships as well as those of some other companies. In particular, they write that “F. Robinson & Co. informed us this day that their ship would sail for Canton in a week at most, they expect Congress will give them liberty, the House of Representatives have already done it”. This ship likely required Congressional approval because of the embargo, passed in March of that year, on ships going from the US to any foreign port.[2] This embargo was passed in response to British ships capturing American ones in the West Indies to interrupt trade with France, as the two were then engaged in the French Revolutionary Wars. Cooke & Co. inform the firm that “there can be nothing certain learnt respecting the continuation of the embargo. Mr. Jay sails for London on Sunday next.” They are probably referring to John Jay, who in 1794 negotiated a treaty between the US and Britain that relieved some of the post-war tension between the countries.

The later letter comes from Joseph Green (who notes having dispatched a ship “immediately after the Embargo”). Besides providing the prices his company would pay for various articles Brown and company had inquired about, Green’s main concern is madeira, a type of wine produced on the eponymous Portuguese island colony. Green describes that year’s vintage as “flattering, and likely to be very abundant”, and anticipates that prices “will be considerably lower than they were the last year”, although “the market continues good”. Madeira was extremely popular in Colonial America; it was famously involved in the 1768 Liberty affair, in which John Hancock was accused of smuggling the wine on his ship Liberty to avoid import taxes, and which led fairly directly to the Boston Massacre. Following the Revolutionary War, Congress had, ironically, passed a series of higher and higher import taxes on items including madeira wine.

Of interest to scholars of mercantile history early in the US’s statehood, and of the rich and powerful families of Rhode Island.

[1] James B. Hedges, “The Brown Papers: The Record of a Rhode Island Business Family”, American Antiquarian Society, April 1941, 21–36.

[2] Jerald A. Combs, The Jay Treaty, Political Battleground of the Founding Fathers (University of California Press, 1970), 120–121.