Collection of Material Relating to African-American Sociologist George E. Haynes, Including Correspondence and Photographs

- Twenty-seven letters, two typed documents (totaling four pages), six photographs, and nine pieces of ephemera including two of H

- United States , 1964

United States, 1964. Twenty-seven letters, two typed documents (totaling four pages), six photographs, and nine pieces of ephemera including two of Haynes’ heavily stamped passports. One of the typed documents and two of the letters belong to Olyve Jeter, Haynes’ second wife. Many items affixed to loose scrapbook leaves. Near Fine.. George Edmund Haynes (1800–1960) was an African American sociologist and social worker. He received a B.A. from Nashville HBCU Fiske University, an M.A. from Yale, and was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Columbia, graduating in 1912. While in New York, Haynes worked with the National League for the Protection of Colored Women and the Committee for Improving the Industrial Conditions of Negroes in New York, and formed the Committee on Urban Conditions among Negroes with white suffragist Ruth Standish Baldwin. These three groups would merge into the National League on Urban Conditions among Negroes—shortened to the National Urban League—in 1911. He taught economics and created the sociology department at Fiske and served as director of the Division of Negro Economics under the US Secretary of Labor. He also served the Federal Council of Churches and with the Joint Committee on National Recovery, which worked to ensure African Americans got their fair share of the New Deal, and had a role in the formation of the State University of New York.

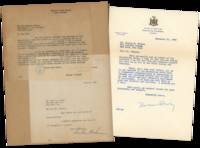

Offered here is a collection of Haynes’ letters with several photographs and documents. The letters, which are sometimes placed alongside copies of Haynes’ outgoing correspondence, come from politicians and influential figures in African American higher education. Those from political figures are generally in response to Haynes sending them his thanks for their advocacy for African Americans: Herbert Hoover personally thanks him for his “fine note of friendship” in response to Haynes’ congratulations on his presidential nomination on the 1928 Republican ticket (June 21, 1928), Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary Louis Howe for his letter in appreciation of the President’s speech against lynching before the Fedral Council of Churches (December 14, 1933), and New York City Mayor Herbert Lehman for his letter in support of the Mayor’s mandate to desegregate CCC camps in the state (April 22, 1937).

The letters from fellow educators are more personal and substantial. In an early letter, Tuskegee president Robert Russa Moton councils Haynes on an unspecified conflict:

“I can see no reason why we should not state your case before the Board. It is quite evident that Mr. Wood misunderstood you. I shall be seeing Dr. Dillard next week at which time I hope to talk over and more in detail the whole situation. [...] The whole thing to me is most unfortunate, especially when the work in hand is so very important and there is so much need for all the forces we can summon to do the work.” (July 8, 1919)

At the time, Haynes was with the Division of Negro Economics, though it is not clear what misunderstanding had occurred or how it related to Tuskegee’s Board. “Dr. Dillard” is almost certainly James H. Dillard, a white advocate for African American education who at the time was the director of the Negro Rural School Fund. Dillard and Haynes seem to have been personal friends, as Dillard laments in a later letter that “I wonder if you and I will ever see each other again. The fates seem against it” (September 24, 1932).

Another friend of Haynes’, Nathan B. Young, writes him in 1931:

“As you may have heard, I am leaving the field of education in Missouri. I am casting about to find something to do. I am still young and healthy with mental powers unabated. I should like to be put into a position where I would have the leisure to ‘write up’ what I have learned by long and varied experience in the field of Negro education. [...] I am asking my friends to make suggestion[s] as to the best use of the leisure immediately before me. Of course, I must keep on earning in order to keep on eating, for I am a poor man.” (May 26, 1931)

A newspaper clipping alongside the letter concerns Young’s unceremonious ouster from the presidency of Lincoln University, an HBCU in Missouri. Young had been removed from the same post in 1927, at least in part because of his efforts to turn the school away from agricultural and industrial education and towards becoming an accredited liberal arts university.[1] He returned to the post in 1929 but was fired again, without a hearing, in 1931; in 1933, after a few years of lecture touring, Young died.

Two letters from newsman Julius J. Adams concern an article that the two were writing about the founding of the National Urban League. Adams writes:

“I am enclosing a copy of a memorandum supplied me by the National Urban League regarding its formation. It is, of course, strictly confidential, but I am eager to get your version of the League’s beginning and desire to see if it coincides. [...] I must say that the manuscript I am working on is being held up by the printers, and it is essential that I get your statement at once. I’d certainly not like to complete the work without including this particular phase of the League. What I’d probably do would be to omit or at least skirt the controversial part of the statement.” (June 14, 1948)

The attached statement, which gives a brief overview of the early years and figures of the Urban League, was authored by Eugene Kinckle Jones. Jones was hired as a secretary to the Committee on Urban Conditions so that Haynes could spend most of his time teaching at Fiske.[2] As Jones notes in the statement, “I was the first full-time employee”, as Haynes “never gave full time to the organization.” It is plausible that this is the ‘controversial’ piece that Adams is worried about: Jones convinced the Committee’s board to give him a more significant role in 1916, and by 1917 became executive secretary, effectively demoting Haynes who then left the League.[3]

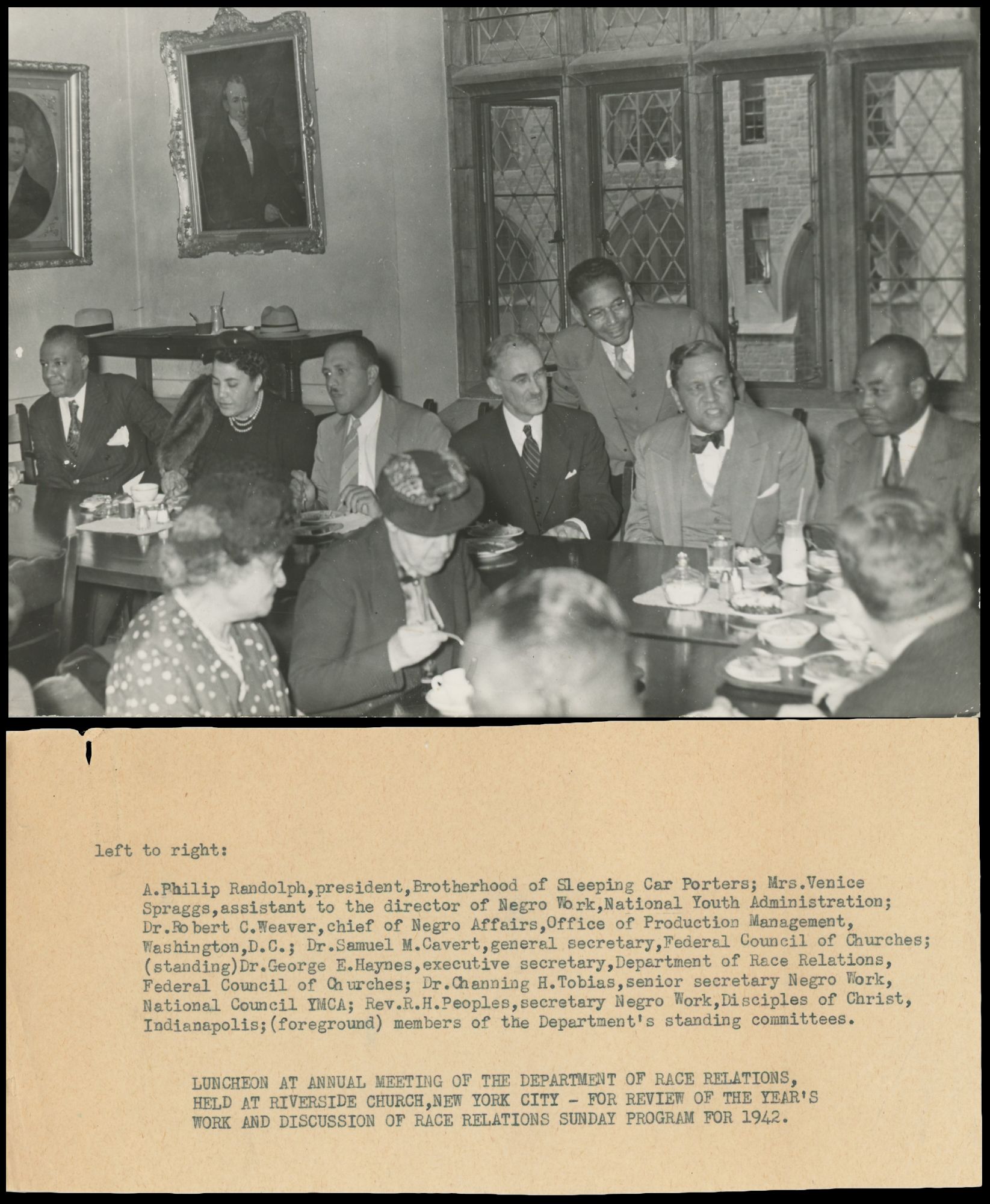

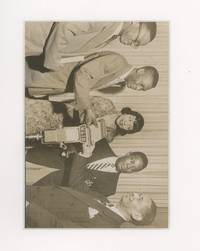

The photographs included in the collection date from the later era of Haynes’ career. Three are of the 1942 annual meeting of the Federal Council of Churches Department of Race Relations. The typed caption states that the subjects of the photo—besides Haynes—include labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph, journalist Venice Spraggs (listed as “assistant to the director of Negro Work”), and academic and politician Robert C. Weaver. The Race Relations commission was created in 1921 with the aim of using Christianity to aid racial relations; Haynes became secretary in 1922 and was executive secretary from 1934 to 1947. A 1948 photo shows Haynes with the Temporary Commission on the Need for a State University, a New York organization that studied college admissions, especially discrimination against African American and Jewish applicants. Its 1948 report, which is being presented to Governor Dewey in this photograph, included the recommendation to set up the SUNY system. Finally, one photograph shows an event at New York City’s WLIN radio station celebrating the release of Haynes’ book Africa: Continent of the Future (1951).

Later letters concern the death of Haynes’ wife Elizabeth Ross Haynes, who died in 1953, with notes of condolence from figures including W.E.B. Du Bois and Adam Clayton Powell. Elizabeth Haynes, a fellow social worker, sociologist, and Fiske graduate, was a distinguished figure in her own right. One letter, from “Sara” in Bronxville, remembers her in some detail:

“Elizabeth spent two afternoons here while in the process of revising ‘Black Boy’ and I spent a day at your house afterward. We had a child-like and easy way of picking up close communication after long intervals of separation. We never talked about Big Issues and all that — but family matters, projects in hand, personal expression in the arts, memories; we always exchanged some disrespectful jokes about women’s organizations — both of us had felt their sticks for a long time — [...] I told her [the first time they met] I meant to get out of teaching colored students before I got helped out by the onrush of young colored teachers. She said that she was quite a lot afraid of giving up her professional work, which she had under reasonable control, for marriage, when she felt no domestic skills and did not even want them much.” (November 24, 1953)

“Black Boy” is Elizabeth Haynes’ The Black Boy of Atlanta (1952), a biography of African American educator, civil rights activist, and entrepreneur Richard R. Wright.

After Elizabeth Haynes’ death, George Haynes married Olyve L. Jeter. Two letters are addressed to her, one from NUL secretary James H. Hubert worrying about “all the lynchings and what-not” in Harlem and considering carrying a weapon (June 2, 1937) and one thanking her for her work with the Citizens for Eisenhower-Nixon, though misspelling her name as “Alyne” (November 7, 1952). Also included is a review authored by Jeter of Charles A. Battle’s pamphlet “Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island”, which seems to have been sent out for publication. The note to the editor states that Jeter was a staff member in the Federal Council of Churches’ Commission on Race Relations.

Haynes’ career significantly impacted both Black academic sociology and employment, housing, and educational conditions for African Americans. Of interest to scholars of Haynes and of African American education in the early and mid century.

[1] Antonio Fredrick Holland, Nathan B. Young and the struggle over Black higher education (Missouri University Press, 2006).

[2] Nancy J. Weiss, The National Urban League, 1910–1940 (Oxford University Press, 1974).

[3] Edgar Allan Toppin, “Haynes, George Edmund”, American National Biography, March 27, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1400270.

Offered here is a collection of Haynes’ letters with several photographs and documents. The letters, which are sometimes placed alongside copies of Haynes’ outgoing correspondence, come from politicians and influential figures in African American higher education. Those from political figures are generally in response to Haynes sending them his thanks for their advocacy for African Americans: Herbert Hoover personally thanks him for his “fine note of friendship” in response to Haynes’ congratulations on his presidential nomination on the 1928 Republican ticket (June 21, 1928), Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary Louis Howe for his letter in appreciation of the President’s speech against lynching before the Fedral Council of Churches (December 14, 1933), and New York City Mayor Herbert Lehman for his letter in support of the Mayor’s mandate to desegregate CCC camps in the state (April 22, 1937).

The letters from fellow educators are more personal and substantial. In an early letter, Tuskegee president Robert Russa Moton councils Haynes on an unspecified conflict:

“I can see no reason why we should not state your case before the Board. It is quite evident that Mr. Wood misunderstood you. I shall be seeing Dr. Dillard next week at which time I hope to talk over and more in detail the whole situation. [...] The whole thing to me is most unfortunate, especially when the work in hand is so very important and there is so much need for all the forces we can summon to do the work.” (July 8, 1919)

At the time, Haynes was with the Division of Negro Economics, though it is not clear what misunderstanding had occurred or how it related to Tuskegee’s Board. “Dr. Dillard” is almost certainly James H. Dillard, a white advocate for African American education who at the time was the director of the Negro Rural School Fund. Dillard and Haynes seem to have been personal friends, as Dillard laments in a later letter that “I wonder if you and I will ever see each other again. The fates seem against it” (September 24, 1932).

Another friend of Haynes’, Nathan B. Young, writes him in 1931:

“As you may have heard, I am leaving the field of education in Missouri. I am casting about to find something to do. I am still young and healthy with mental powers unabated. I should like to be put into a position where I would have the leisure to ‘write up’ what I have learned by long and varied experience in the field of Negro education. [...] I am asking my friends to make suggestion[s] as to the best use of the leisure immediately before me. Of course, I must keep on earning in order to keep on eating, for I am a poor man.” (May 26, 1931)

A newspaper clipping alongside the letter concerns Young’s unceremonious ouster from the presidency of Lincoln University, an HBCU in Missouri. Young had been removed from the same post in 1927, at least in part because of his efforts to turn the school away from agricultural and industrial education and towards becoming an accredited liberal arts university.[1] He returned to the post in 1929 but was fired again, without a hearing, in 1931; in 1933, after a few years of lecture touring, Young died.

Two letters from newsman Julius J. Adams concern an article that the two were writing about the founding of the National Urban League. Adams writes:

“I am enclosing a copy of a memorandum supplied me by the National Urban League regarding its formation. It is, of course, strictly confidential, but I am eager to get your version of the League’s beginning and desire to see if it coincides. [...] I must say that the manuscript I am working on is being held up by the printers, and it is essential that I get your statement at once. I’d certainly not like to complete the work without including this particular phase of the League. What I’d probably do would be to omit or at least skirt the controversial part of the statement.” (June 14, 1948)

The attached statement, which gives a brief overview of the early years and figures of the Urban League, was authored by Eugene Kinckle Jones. Jones was hired as a secretary to the Committee on Urban Conditions so that Haynes could spend most of his time teaching at Fiske.[2] As Jones notes in the statement, “I was the first full-time employee”, as Haynes “never gave full time to the organization.” It is plausible that this is the ‘controversial’ piece that Adams is worried about: Jones convinced the Committee’s board to give him a more significant role in 1916, and by 1917 became executive secretary, effectively demoting Haynes who then left the League.[3]

The photographs included in the collection date from the later era of Haynes’ career. Three are of the 1942 annual meeting of the Federal Council of Churches Department of Race Relations. The typed caption states that the subjects of the photo—besides Haynes—include labor and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph, journalist Venice Spraggs (listed as “assistant to the director of Negro Work”), and academic and politician Robert C. Weaver. The Race Relations commission was created in 1921 with the aim of using Christianity to aid racial relations; Haynes became secretary in 1922 and was executive secretary from 1934 to 1947. A 1948 photo shows Haynes with the Temporary Commission on the Need for a State University, a New York organization that studied college admissions, especially discrimination against African American and Jewish applicants. Its 1948 report, which is being presented to Governor Dewey in this photograph, included the recommendation to set up the SUNY system. Finally, one photograph shows an event at New York City’s WLIN radio station celebrating the release of Haynes’ book Africa: Continent of the Future (1951).

Later letters concern the death of Haynes’ wife Elizabeth Ross Haynes, who died in 1953, with notes of condolence from figures including W.E.B. Du Bois and Adam Clayton Powell. Elizabeth Haynes, a fellow social worker, sociologist, and Fiske graduate, was a distinguished figure in her own right. One letter, from “Sara” in Bronxville, remembers her in some detail:

“Elizabeth spent two afternoons here while in the process of revising ‘Black Boy’ and I spent a day at your house afterward. We had a child-like and easy way of picking up close communication after long intervals of separation. We never talked about Big Issues and all that — but family matters, projects in hand, personal expression in the arts, memories; we always exchanged some disrespectful jokes about women’s organizations — both of us had felt their sticks for a long time — [...] I told her [the first time they met] I meant to get out of teaching colored students before I got helped out by the onrush of young colored teachers. She said that she was quite a lot afraid of giving up her professional work, which she had under reasonable control, for marriage, when she felt no domestic skills and did not even want them much.” (November 24, 1953)

“Black Boy” is Elizabeth Haynes’ The Black Boy of Atlanta (1952), a biography of African American educator, civil rights activist, and entrepreneur Richard R. Wright.

After Elizabeth Haynes’ death, George Haynes married Olyve L. Jeter. Two letters are addressed to her, one from NUL secretary James H. Hubert worrying about “all the lynchings and what-not” in Harlem and considering carrying a weapon (June 2, 1937) and one thanking her for her work with the Citizens for Eisenhower-Nixon, though misspelling her name as “Alyne” (November 7, 1952). Also included is a review authored by Jeter of Charles A. Battle’s pamphlet “Negroes on the Island of Rhode Island”, which seems to have been sent out for publication. The note to the editor states that Jeter was a staff member in the Federal Council of Churches’ Commission on Race Relations.

Haynes’ career significantly impacted both Black academic sociology and employment, housing, and educational conditions for African Americans. Of interest to scholars of Haynes and of African American education in the early and mid century.

[1] Antonio Fredrick Holland, Nathan B. Young and the struggle over Black higher education (Missouri University Press, 2006).

[2] Nancy J. Weiss, The National Urban League, 1910–1940 (Oxford University Press, 1974).

[3] Edgar Allan Toppin, “Haynes, George Edmund”, American National Biography, March 27, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1400270.