Two 1857 Legal Documents Concerning a Married Woman’s Right to the Sole Ownership of an Enslaved Woman and Her Children

- Two documents, totaling five double-sided pages measuring 8 x 13 inches and six double-sided pages measuring 7 ½ x 12 inches

- Wilcox County, Alabama , 1857

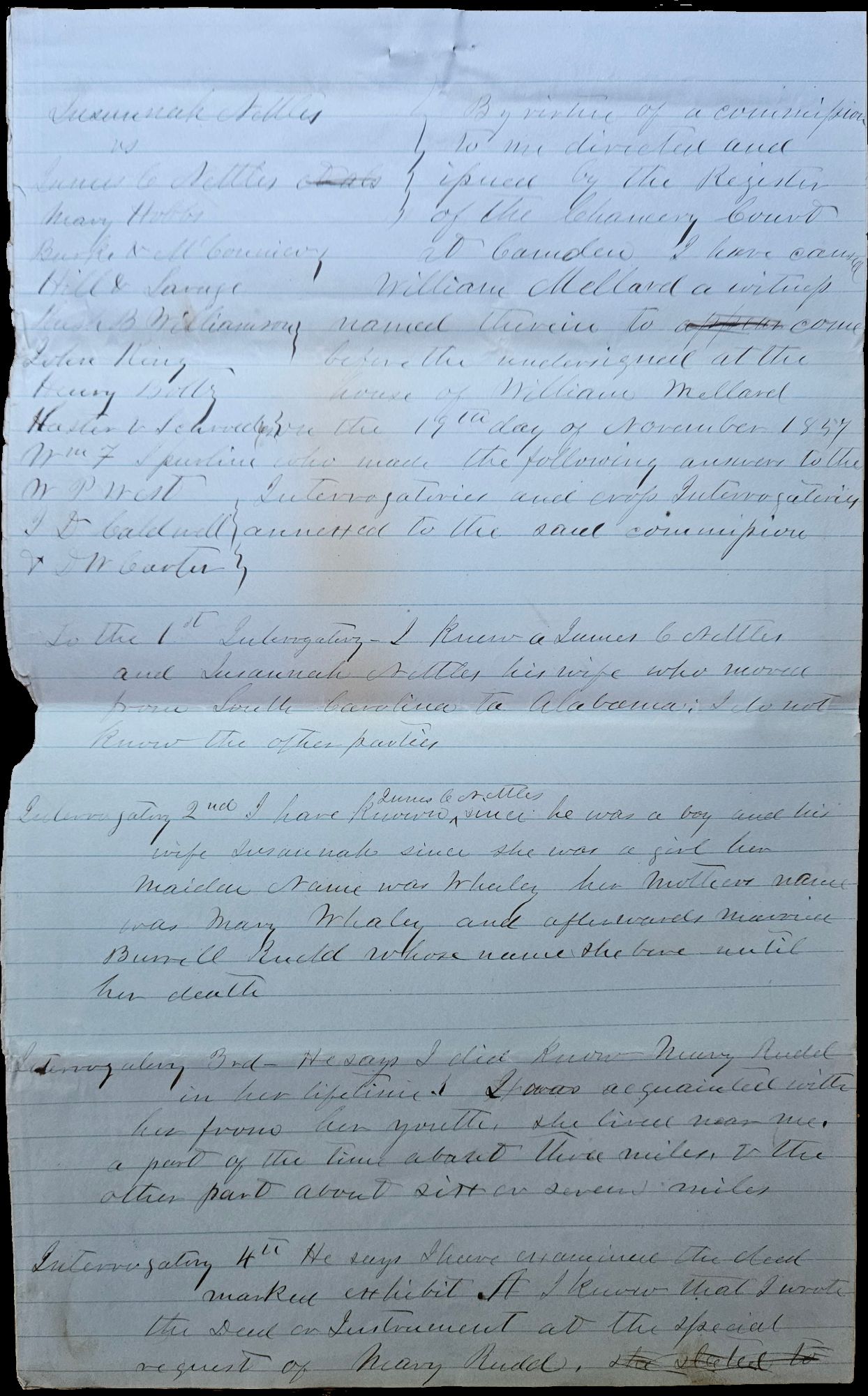

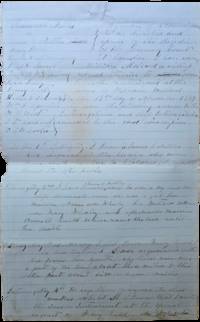

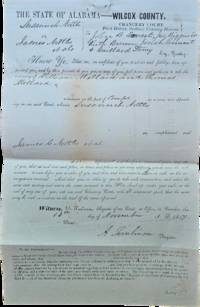

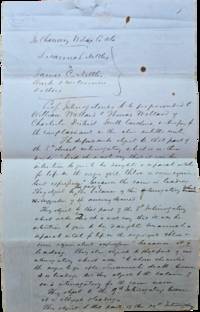

Wilcox County, Alabama, 1857. Two documents, totaling five double-sided pages measuring 8 x 13 inches and six double-sided pages measuring 7 ½ x 12 inches. Folded with some stains and wear; Near Fine.. Two legal documents from an Alabama chancery court suit brought against Susannah Nettles by her husband, James C. Nettles, concerning ownership of an enslaved woman named Chloe. The documents are a set of cross interrogatories and objections and their replies, which were given by William Mellard, the writer of the deed that originally gave Susannah ownership of Chloe. Mellard recalls that the deed, written in 1829, provided the following:

"Mary Rudd declared to him while directing him how to write the Instrument, that as Susannah was her youngest child and a daughter, that she wished while she yet lived to secure to her that much of her Estate, to wit, Chloe and her future increase; and she wished the Instrument so written that it would convey to Susannah the said girl Chloe, in such a manner that she would not be subject to the control of her husband should she afterwards marry [...] and that the negro girl should not be subject to the debts of her husband should she marry".

Mellard claims that, after Susannah's marriage, "James C. Nettles admitted the right of his wife to the Negroes and acquiesced in her title to them, and did not claim any right to them."

At the time the deed was drawn up, the legal doctrine of coverture was in effect: a married woman did not have legal rights and obligations, including a right to property ownership, separate from her husband. Though Susannah was single at the time, Chloe would have become James Nettles' property on his marriage to Susannah were it not for the part of Mary Rudd's deed, which Mellard insists he is remembering correctly, that set aside Chloe as only Susannah's property. Though some states had passed Married Women's Property Acts or similar, Alabama would pass any such laws until 1867.[1]

These documents are a striking example of the enforcement of a key aspect of women's rights—the right to own one's own property—in which it specifically hinges on the denial of rights to another group of women—those who are owned as property. Of interest to legal historians, particularly of women's rights and enslavement.

[1] B. Zorina Khan, The Democratization of Invention: Patents and Copyrights in American Economic Development, 1790–1920 (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 167.

"Mary Rudd declared to him while directing him how to write the Instrument, that as Susannah was her youngest child and a daughter, that she wished while she yet lived to secure to her that much of her Estate, to wit, Chloe and her future increase; and she wished the Instrument so written that it would convey to Susannah the said girl Chloe, in such a manner that she would not be subject to the control of her husband should she afterwards marry [...] and that the negro girl should not be subject to the debts of her husband should she marry".

Mellard claims that, after Susannah's marriage, "James C. Nettles admitted the right of his wife to the Negroes and acquiesced in her title to them, and did not claim any right to them."

At the time the deed was drawn up, the legal doctrine of coverture was in effect: a married woman did not have legal rights and obligations, including a right to property ownership, separate from her husband. Though Susannah was single at the time, Chloe would have become James Nettles' property on his marriage to Susannah were it not for the part of Mary Rudd's deed, which Mellard insists he is remembering correctly, that set aside Chloe as only Susannah's property. Though some states had passed Married Women's Property Acts or similar, Alabama would pass any such laws until 1867.[1]

These documents are a striking example of the enforcement of a key aspect of women's rights—the right to own one's own property—in which it specifically hinges on the denial of rights to another group of women—those who are owned as property. Of interest to legal historians, particularly of women's rights and enslavement.

[1] B. Zorina Khan, The Democratization of Invention: Patents and Copyrights in American Economic Development, 1790–1920 (Cambridge University Press, 2005), 167.