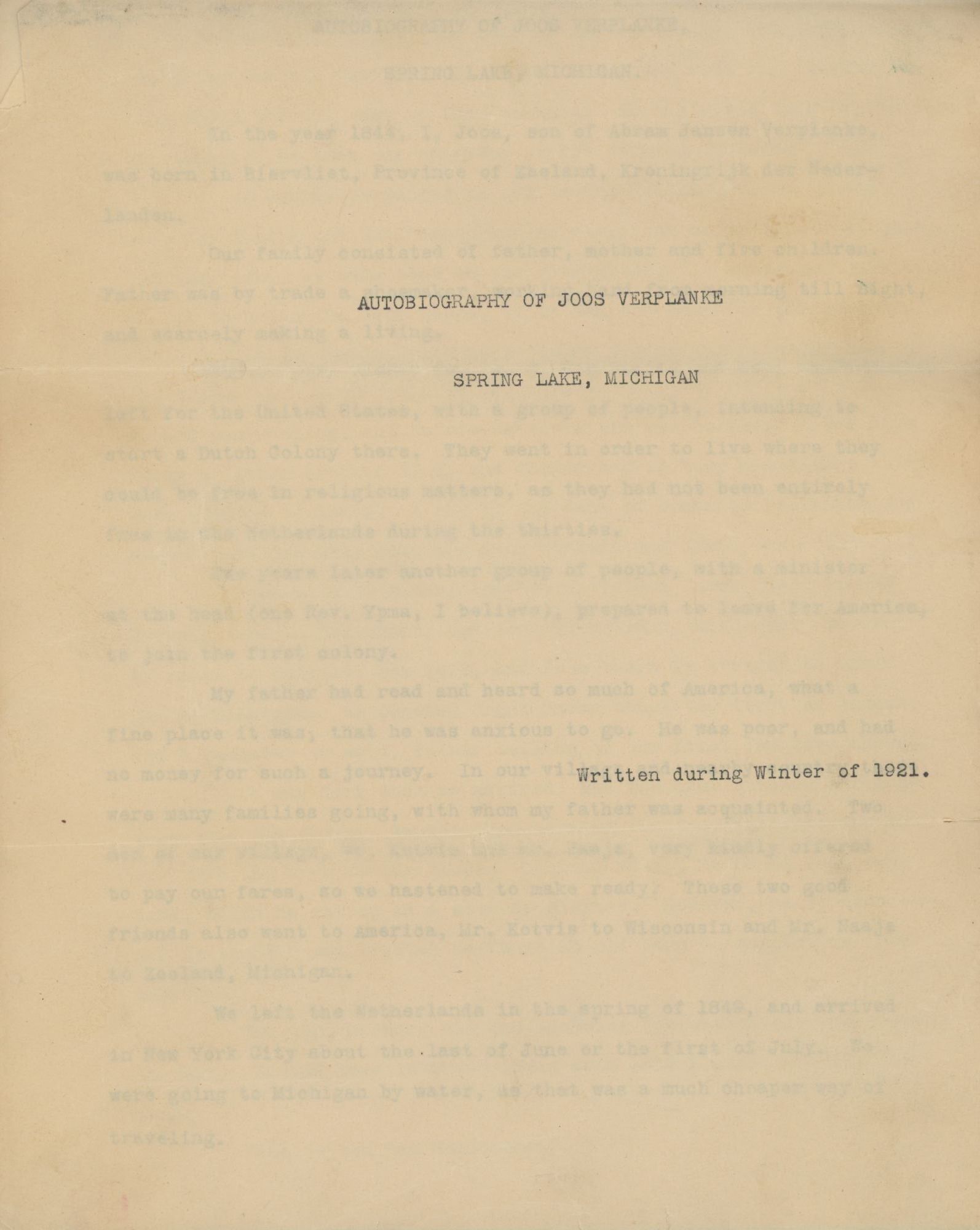

Autobiography of Joos Verplanke, Spring Lake, Michigan, Written during Winter of 1921

- Twelve 8 ½ x 11 inch pages affixed to backing sheet

- Spring Lake, Michigan , 1921

Spring Lake, Michigan, 1921. Twelve 8 ½ x 11 inch pages affixed to backing sheet. Wear, marginal damage, and some tearing to backing sheet; pages folded with some wrinkling; excellent.. Joos Verplanke (1844–1943) was born in Zeeland, The Netherlands, and immigrated with his family to the United States in 1849. They settled in Holland, Michigan, and besides his time serving in the Union Army, Verplanke would live in the Ottawa County area for the rest of his life. Offered here is a short memoir written by Verplanke for his children in 1921, when he was in his late 70s.

The Verplanke family came to the US as part of the wave of immigration that followed the Dutch Reformed Church secession and the economic downturn in The Netherlands in the 1830s. Some Seceder church leaders, such as Albertus Van Raalte, felt that they were being religiously persecuted by the government and that staying in The Netherlands was religiously and economically untenable for their congregants.[1] By the mid-1840s, several Seceder ministers had formed emigration societies to help their parishioners leave for the US. As Verplanke puts it, “They went in order to live where they could be free in religious matters, as they had not been entirely free in the Netherlands during the thirties.”

Joos Verplanke and his family left Biervliet, Zeeland, in 1849 to join the Dutch colony in what would become Holland, Michigan—but they and others in their party ran out of funds by Albany. The group was sent to “the Poor House”; many, including Verplanke’s mother and younger brother, died from cholera, and the group was forced to leave. Arriving in Grand Haven, Michigan, they were assisted by a farmer who had also immigrated from The Netherlands a few years prior. The farmer fed and housed the family and eventually raised funds for them to continue to Holland. In fact, this ethos was important to the Dutch immigrants; some Seceder emigration societies had provisions that money would be pooled so that the richer immigrants could help the poorer reach the colony.[1]

The Verplankes arrived destitute in Holland. Joos Verplanke describes the colony:

“Holland was a very new colony, practically in the woods, with a few stores, a few small houses. The Government land was taken up by these colonists. Rev. VanDerMeulen had settled in Zeeland. Rev. Ypma im Vriesland, Rev. Bolks in Overisel, and others in Graafscap; each in his colony. A few of the immigrants had money, but most had just enough to get them here. It was very hard for them in this wild, timbered country, so different from the cultivated and thickly settled Netherlands. None of them had ever handled an axe. [...] However encouraged by their ministers, they were determined to learn to use the axe and chop out a place where they could worship God as they wished, which they had not been allowed to do in the Netherlands some time before.”

In 1862 Verplanke enlisted with the Union Army. He recalls training:

“We were in Holland two weeks training. Had a jolly time, everyone was good to us. We could have anything we wanted. All the beer we wanted to, as there was no prohibition those days.”

He recalls the unit fighting Morgan’s raiders at “Tip’s Bend” (Tebbs Bend, Kentucky), fighting in Knoxville, and with Sherman on his March to the Sea. He also recalls his short-lived desertion from the steamer Matanzas in Washington:

“So crowded was the boat that there was no room to lie down, not even on the upper deck. I thought, if I can get off I will not go with this boat. I talked to a few of the boys, and they agreed with me. Just then the gang planks were hauled in, so we could not sneak off that way. I looked over, and noticed along the boat’s side the whale-fenders were hanging by ropes. We threw our knapsacks and slide [sic] down the ropes. [...] The next morning we went to headquarters and I told some kind of a story about getting left. [...] Though we had been booked as deserters, there was nothing more said of it. So we remembered only the fun we had out of what might have proved to be a very bad venture.”

Verplanke mustered out in June of 1865. He became the town marshall in Holland and in 1876 successfully ran as a Democrat for Ottawa County Sheriff despite the county’s Republican lean. He ran again two years later as a Greenback. The Greenback Party was an agrarian anti-monopoly and pro- monetary and labor reform party, but Verplanke frames his running as a Greenback as a practical decision: “I knew if I accepted the Greenback nomination I was almost certain of victory. [...] I needed it badly as I had spent so much money in electioneering” for the previous election.

Verplanke farmed in Crockery Township and then moved to Spring Lake, where he authored this document for the benefit of his nine living sons.

Of interest to scholars of the Dutch settlement of Michigan following the Dutch Reformed Church split, and those immigrants’ participation in the Civil War and American political life.

[1] Robert P. Swierenga, “‘By the Sweat of our Brow’: Economic Aspects of the Dutch Immigration to Michigan”, lecture at the A.C. Van Raalte Institute for Historical Studies, Hope College, Holland Museum Sesquicentennial Lecture Series, Holland, MI, March 13, 1997.

The Verplanke family came to the US as part of the wave of immigration that followed the Dutch Reformed Church secession and the economic downturn in The Netherlands in the 1830s. Some Seceder church leaders, such as Albertus Van Raalte, felt that they were being religiously persecuted by the government and that staying in The Netherlands was religiously and economically untenable for their congregants.[1] By the mid-1840s, several Seceder ministers had formed emigration societies to help their parishioners leave for the US. As Verplanke puts it, “They went in order to live where they could be free in religious matters, as they had not been entirely free in the Netherlands during the thirties.”

Joos Verplanke and his family left Biervliet, Zeeland, in 1849 to join the Dutch colony in what would become Holland, Michigan—but they and others in their party ran out of funds by Albany. The group was sent to “the Poor House”; many, including Verplanke’s mother and younger brother, died from cholera, and the group was forced to leave. Arriving in Grand Haven, Michigan, they were assisted by a farmer who had also immigrated from The Netherlands a few years prior. The farmer fed and housed the family and eventually raised funds for them to continue to Holland. In fact, this ethos was important to the Dutch immigrants; some Seceder emigration societies had provisions that money would be pooled so that the richer immigrants could help the poorer reach the colony.[1]

The Verplankes arrived destitute in Holland. Joos Verplanke describes the colony:

“Holland was a very new colony, practically in the woods, with a few stores, a few small houses. The Government land was taken up by these colonists. Rev. VanDerMeulen had settled in Zeeland. Rev. Ypma im Vriesland, Rev. Bolks in Overisel, and others in Graafscap; each in his colony. A few of the immigrants had money, but most had just enough to get them here. It was very hard for them in this wild, timbered country, so different from the cultivated and thickly settled Netherlands. None of them had ever handled an axe. [...] However encouraged by their ministers, they were determined to learn to use the axe and chop out a place where they could worship God as they wished, which they had not been allowed to do in the Netherlands some time before.”

In 1862 Verplanke enlisted with the Union Army. He recalls training:

“We were in Holland two weeks training. Had a jolly time, everyone was good to us. We could have anything we wanted. All the beer we wanted to, as there was no prohibition those days.”

He recalls the unit fighting Morgan’s raiders at “Tip’s Bend” (Tebbs Bend, Kentucky), fighting in Knoxville, and with Sherman on his March to the Sea. He also recalls his short-lived desertion from the steamer Matanzas in Washington:

“So crowded was the boat that there was no room to lie down, not even on the upper deck. I thought, if I can get off I will not go with this boat. I talked to a few of the boys, and they agreed with me. Just then the gang planks were hauled in, so we could not sneak off that way. I looked over, and noticed along the boat’s side the whale-fenders were hanging by ropes. We threw our knapsacks and slide [sic] down the ropes. [...] The next morning we went to headquarters and I told some kind of a story about getting left. [...] Though we had been booked as deserters, there was nothing more said of it. So we remembered only the fun we had out of what might have proved to be a very bad venture.”

Verplanke mustered out in June of 1865. He became the town marshall in Holland and in 1876 successfully ran as a Democrat for Ottawa County Sheriff despite the county’s Republican lean. He ran again two years later as a Greenback. The Greenback Party was an agrarian anti-monopoly and pro- monetary and labor reform party, but Verplanke frames his running as a Greenback as a practical decision: “I knew if I accepted the Greenback nomination I was almost certain of victory. [...] I needed it badly as I had spent so much money in electioneering” for the previous election.

Verplanke farmed in Crockery Township and then moved to Spring Lake, where he authored this document for the benefit of his nine living sons.

Of interest to scholars of the Dutch settlement of Michigan following the Dutch Reformed Church split, and those immigrants’ participation in the Civil War and American political life.

[1] Robert P. Swierenga, “‘By the Sweat of our Brow’: Economic Aspects of the Dutch Immigration to Michigan”, lecture at the A.C. Van Raalte Institute for Historical Studies, Hope College, Holland Museum Sesquicentennial Lecture Series, Holland, MI, March 13, 1997.