Letters Home from an American Professor Working in the Ottoman Empire in the Aftermath of World War I.

- Four letters totaling seven pages

- Constantinople, New York City, and others , 1922

Constantinople, New York City, and others, 1922. Four letters totaling seven pages. Folded, else fine.. A small collection of letters from “H.C.”, who seems to have been an American university professor in Constantinople, to his “Darling Clementine” back home. H.C. may have taught at Robert College, a Christian college founded in 1863, now a prestigious private highschool.

It is not clear when H.C. first arrived in Constantinople, but he had been there for several years already by the time the letters begin, and was certainly there at a critical point in its history. He writes in 1918 shortly after the arrival of occupying forces:

“conditions are still very bad in town + I long to see the suffering diminished. Some say it will be months yet. Sometimes, now, there is no coal, no electric light, no bread, no water. Can you imagine the state of an Oriental city under such conditions? We have had + are still having trouble about light + water-supply, but we have steam heat + plenty of food of a plain kind. We all keep well. [...] I hear that an American Red Cross boat will arrive next week + I am eager to see its passengers. We may have a chance to leave on it but I can not see my way clear to skip because our faculty is depleted ever since the exodus at the time of the panic long ago, when Miss Lyon left. [...] We have a good college now – boarders about 90 in the College-department – and many day scholars, but lately the Spanish fever + the lack of tram-car service has kept many students away. As soon as our cousins supply coal, we hope for improvement. The Ententists are spreading over the city thoroughly + quietly – like oil. It is a delight to see so many manly looking officers after the ones we have had here for years. There is a spiritual look in the eyes of the present occupants + a look of bull-dog determination.” (December 6, 1918)

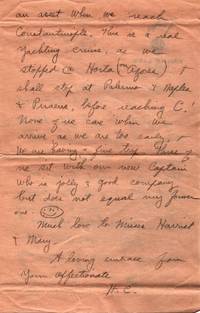

H.C. enjoys a “real yachting cruise” on his way back to Constantinople from the States in 1921, tells Clementine about his plans for his commencement speech in 1922, and describes a college reception in New York City which “General Custer’s wife”, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, attended (undated letter). Meanwhile, Turkey was engaged in its brutal war for independence. At some point, H.C. befriended Electra—probably a Greek woman—whom he sent along to visit Clementine, in part to help Electra cope with her traumatic experiences during the war:

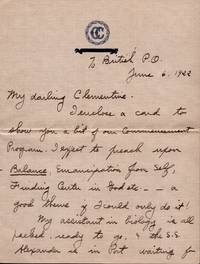

“As you will recall, my young friend’s father was executed – tho innocent – with about 70 others. At first E. bore this with wonderful fortitude but after Xmas a reaction set in, naturally enough. She developed morbidness + a hyper sensitive attitude toward all of my looks + words – probably a condition due to shock. I am confident that travel + new scenes + interests will bring her back to her old self + your wholesome household will chase all gloom away. A doctor told her lately that she has hysteria + that she must think of cheerful things, only. I tell you this, thinking that you might keep her from talking about the nation that does cruel things. The truth is that cruelty is pretty generally distributed + a judicial mind finds it difficult to pick + choose. Some nations get the public ear + so the pot can call the kettle black!” (June 6, 1922)

Indeed, both sides of the Greco-Turkish war—part of the larger Turkish campaign for independence—massacred each other. However, only the Turkish contingent’s actions have been argued by historians to constitute ethnic cleansing or genocide.

Of interest to historians of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey post-World War I, especially Americans’ experience thereof.

It is not clear when H.C. first arrived in Constantinople, but he had been there for several years already by the time the letters begin, and was certainly there at a critical point in its history. He writes in 1918 shortly after the arrival of occupying forces:

“conditions are still very bad in town + I long to see the suffering diminished. Some say it will be months yet. Sometimes, now, there is no coal, no electric light, no bread, no water. Can you imagine the state of an Oriental city under such conditions? We have had + are still having trouble about light + water-supply, but we have steam heat + plenty of food of a plain kind. We all keep well. [...] I hear that an American Red Cross boat will arrive next week + I am eager to see its passengers. We may have a chance to leave on it but I can not see my way clear to skip because our faculty is depleted ever since the exodus at the time of the panic long ago, when Miss Lyon left. [...] We have a good college now – boarders about 90 in the College-department – and many day scholars, but lately the Spanish fever + the lack of tram-car service has kept many students away. As soon as our cousins supply coal, we hope for improvement. The Ententists are spreading over the city thoroughly + quietly – like oil. It is a delight to see so many manly looking officers after the ones we have had here for years. There is a spiritual look in the eyes of the present occupants + a look of bull-dog determination.” (December 6, 1918)

H.C. enjoys a “real yachting cruise” on his way back to Constantinople from the States in 1921, tells Clementine about his plans for his commencement speech in 1922, and describes a college reception in New York City which “General Custer’s wife”, Elizabeth Bacon Custer, attended (undated letter). Meanwhile, Turkey was engaged in its brutal war for independence. At some point, H.C. befriended Electra—probably a Greek woman—whom he sent along to visit Clementine, in part to help Electra cope with her traumatic experiences during the war:

“As you will recall, my young friend’s father was executed – tho innocent – with about 70 others. At first E. bore this with wonderful fortitude but after Xmas a reaction set in, naturally enough. She developed morbidness + a hyper sensitive attitude toward all of my looks + words – probably a condition due to shock. I am confident that travel + new scenes + interests will bring her back to her old self + your wholesome household will chase all gloom away. A doctor told her lately that she has hysteria + that she must think of cheerful things, only. I tell you this, thinking that you might keep her from talking about the nation that does cruel things. The truth is that cruelty is pretty generally distributed + a judicial mind finds it difficult to pick + choose. Some nations get the public ear + so the pot can call the kettle black!” (June 6, 1922)

Indeed, both sides of the Greco-Turkish war—part of the larger Turkish campaign for independence—massacred each other. However, only the Turkish contingent’s actions have been argued by historians to constitute ethnic cleansing or genocide.

Of interest to historians of the Ottoman Empire and Turkey post-World War I, especially Americans’ experience thereof.