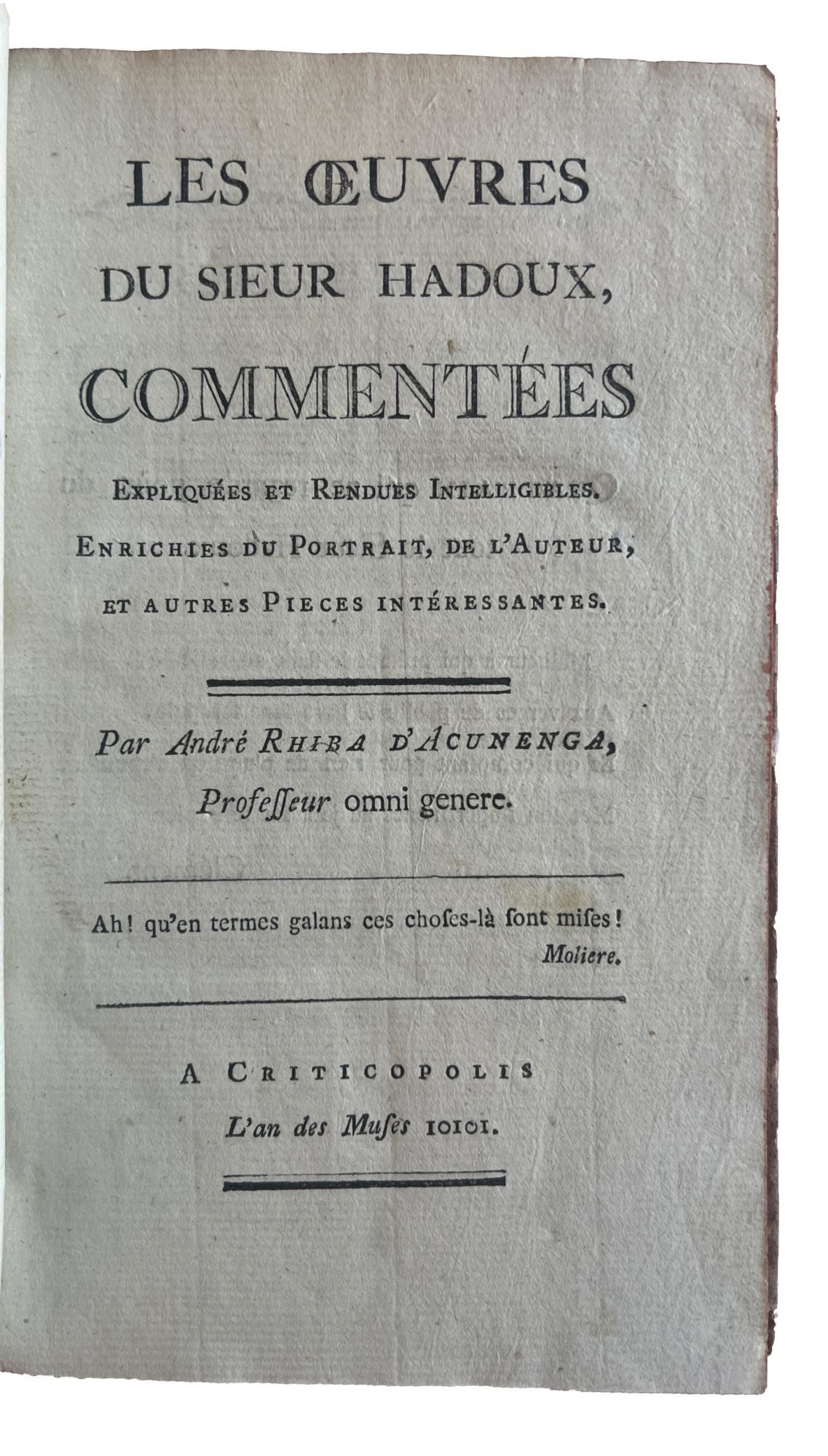

Les oeuvres du Sieur Hadoux, commentées expliquées et rendues intelligibles. Enrichies du portrait, de l'auteur, et autres Pièces intéressantes

- SIGNED

- “A Criticopolis” [i.e., Holland]: s.n., 1783

“A Criticopolis” [i.e., Holland]: s.n., 1783. 8vo (195 x 116 mm.). 187 pages (including half-title Commentaire sur les oeuvres...). Type-ornament tailpieces and dividers. Contemporary mottled quarter calf, smooth spine gilt and with green morocco lettering piece, edges stained red (joints restored, corners bumped). ***

Only Edition of a surreal literary spoof, mocking erudition and critical apparatuses. Under the anagram André Rhiba d’Acunenga, the author presents the idiosyncratically spelled “Euvres” of the fictional author Hadoux (printed in Criticopolis or the “city of critics”) in an elaborate scaffolding of tongue-in-cheek commentary. Opening with a “Prefaciuncule,” the long preliminary material includes a snappy verse epistle to the author, a verbal portrait, also in verse, of the same (preceded by an Avis “essenciel” explaining why the “poetic brush” is preferable to an engraving), several more silly forewords and epistles, and a title-page facsimile. Each of these paratextual elements has its own footnoted commentary.

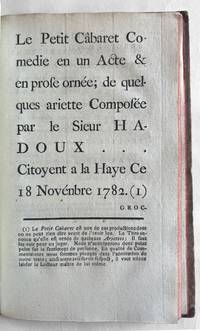

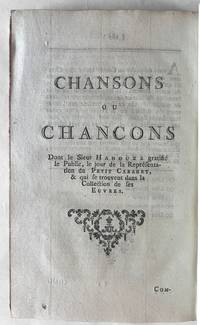

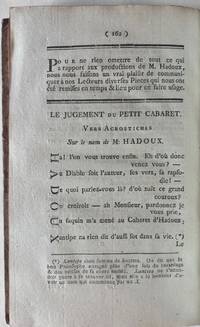

The two plays of Sir Hadoux, The Green Dragon and The Little Cabaret, which the preliminaries promised NOT to include, mainly provide an excuse for extravagantly laudatory afterwords (”Molière had nothing on le Sieur Hadoux”...) and droll footnotes filled with pseudo-erudite and/or punning remarks on word choice and etymology, fictional biographical details, and chatty digressions. The edition concludes with Hadoux’s minor works (under the crudely punning title Chansons ou Chancons) and more satirical annotations. The “editor” alludes throughout to typographical details of the edition itself, which makes use of a variety of fonts and typographical devices, including an acrostic with letters printed sideways.

The true author, Brahain Ducange, was a Dutch-French journalist and evidently talented international secret agent. Early in his career he lived in the Hague and Leiden, wrote for the Leiden Gazette (the most important international news source of the time), and later published his own short-lived political periodical there, Le Batave, ou le Sans-Culotte (1793-1794). His involvement in revolutionary politics allegedly included a collaboration with Robespierre’s police during the Terror, and he is said to have worked as an operative in the Batavian coup d’état in 1798. The Wikipedia entry, relying on a biography of the Dutch general Herman Willem Daendels, portrays Brahain Ducange as a conman who betrayed confidences, tricked ambassadors, and swindled his way from the Netherlands through France, Spain, Germany and Austria. Between stays in prison he worked for various embassies. Michaud, editor of the Nouvelle Biographie Générale, wrote that he knew Ducange personally, and that he had “the reserved and polite demeanor of a former diplomat” (NBG 12:377, note to entry on Ducange’s son, the writer Victor Henri Joseph Brahain Ducange). Toward the end of his mysterious life Ducange was forced to fall back on his literary talents, as a copywriter and editor for the children’s book publisher Alexis Eymery.

The edition was probably printed in the Netherlands. The signatures on five of the eight leaves in the quires, use of catchwords on each page, and page numbers enclosed in parentheses are all practices associated with Dutch books (cf. Sayce, Compositorial practices).

I locate no American institutional copies of this unusual satire, which evokes Sterne as well as Borges (7 copies located: Royal Library of the Netherlands, Gemeentearchief, BnF (2 copies), Bordeaux Municipal Library, Augsburg, British Library).

Short-Title Catalogue Netherlands 24060494; Quérard, Superchéries littéraires IV: 109, no. 6511; Paul Lacroix, ed., Bibliothèque dramatique de Monsieur de Soleinne II: 194, no. 2296; Conlon, Siècle des Lumières 83: 1019; Weller, Die falschen und fingierten Druckorte II:221.

Only Edition of a surreal literary spoof, mocking erudition and critical apparatuses. Under the anagram André Rhiba d’Acunenga, the author presents the idiosyncratically spelled “Euvres” of the fictional author Hadoux (printed in Criticopolis or the “city of critics”) in an elaborate scaffolding of tongue-in-cheek commentary. Opening with a “Prefaciuncule,” the long preliminary material includes a snappy verse epistle to the author, a verbal portrait, also in verse, of the same (preceded by an Avis “essenciel” explaining why the “poetic brush” is preferable to an engraving), several more silly forewords and epistles, and a title-page facsimile. Each of these paratextual elements has its own footnoted commentary.

The two plays of Sir Hadoux, The Green Dragon and The Little Cabaret, which the preliminaries promised NOT to include, mainly provide an excuse for extravagantly laudatory afterwords (”Molière had nothing on le Sieur Hadoux”...) and droll footnotes filled with pseudo-erudite and/or punning remarks on word choice and etymology, fictional biographical details, and chatty digressions. The edition concludes with Hadoux’s minor works (under the crudely punning title Chansons ou Chancons) and more satirical annotations. The “editor” alludes throughout to typographical details of the edition itself, which makes use of a variety of fonts and typographical devices, including an acrostic with letters printed sideways.

The true author, Brahain Ducange, was a Dutch-French journalist and evidently talented international secret agent. Early in his career he lived in the Hague and Leiden, wrote for the Leiden Gazette (the most important international news source of the time), and later published his own short-lived political periodical there, Le Batave, ou le Sans-Culotte (1793-1794). His involvement in revolutionary politics allegedly included a collaboration with Robespierre’s police during the Terror, and he is said to have worked as an operative in the Batavian coup d’état in 1798. The Wikipedia entry, relying on a biography of the Dutch general Herman Willem Daendels, portrays Brahain Ducange as a conman who betrayed confidences, tricked ambassadors, and swindled his way from the Netherlands through France, Spain, Germany and Austria. Between stays in prison he worked for various embassies. Michaud, editor of the Nouvelle Biographie Générale, wrote that he knew Ducange personally, and that he had “the reserved and polite demeanor of a former diplomat” (NBG 12:377, note to entry on Ducange’s son, the writer Victor Henri Joseph Brahain Ducange). Toward the end of his mysterious life Ducange was forced to fall back on his literary talents, as a copywriter and editor for the children’s book publisher Alexis Eymery.

The edition was probably printed in the Netherlands. The signatures on five of the eight leaves in the quires, use of catchwords on each page, and page numbers enclosed in parentheses are all practices associated with Dutch books (cf. Sayce, Compositorial practices).

I locate no American institutional copies of this unusual satire, which evokes Sterne as well as Borges (7 copies located: Royal Library of the Netherlands, Gemeentearchief, BnF (2 copies), Bordeaux Municipal Library, Augsburg, British Library).

Short-Title Catalogue Netherlands 24060494; Quérard, Superchéries littéraires IV: 109, no. 6511; Paul Lacroix, ed., Bibliothèque dramatique de Monsieur de Soleinne II: 194, no. 2296; Conlon, Siècle des Lumières 83: 1019; Weller, Die falschen und fingierten Druckorte II:221.