Tabulae physiognomicae

- SIGNED

- Venice: Gaspare Corradiccio, 1639

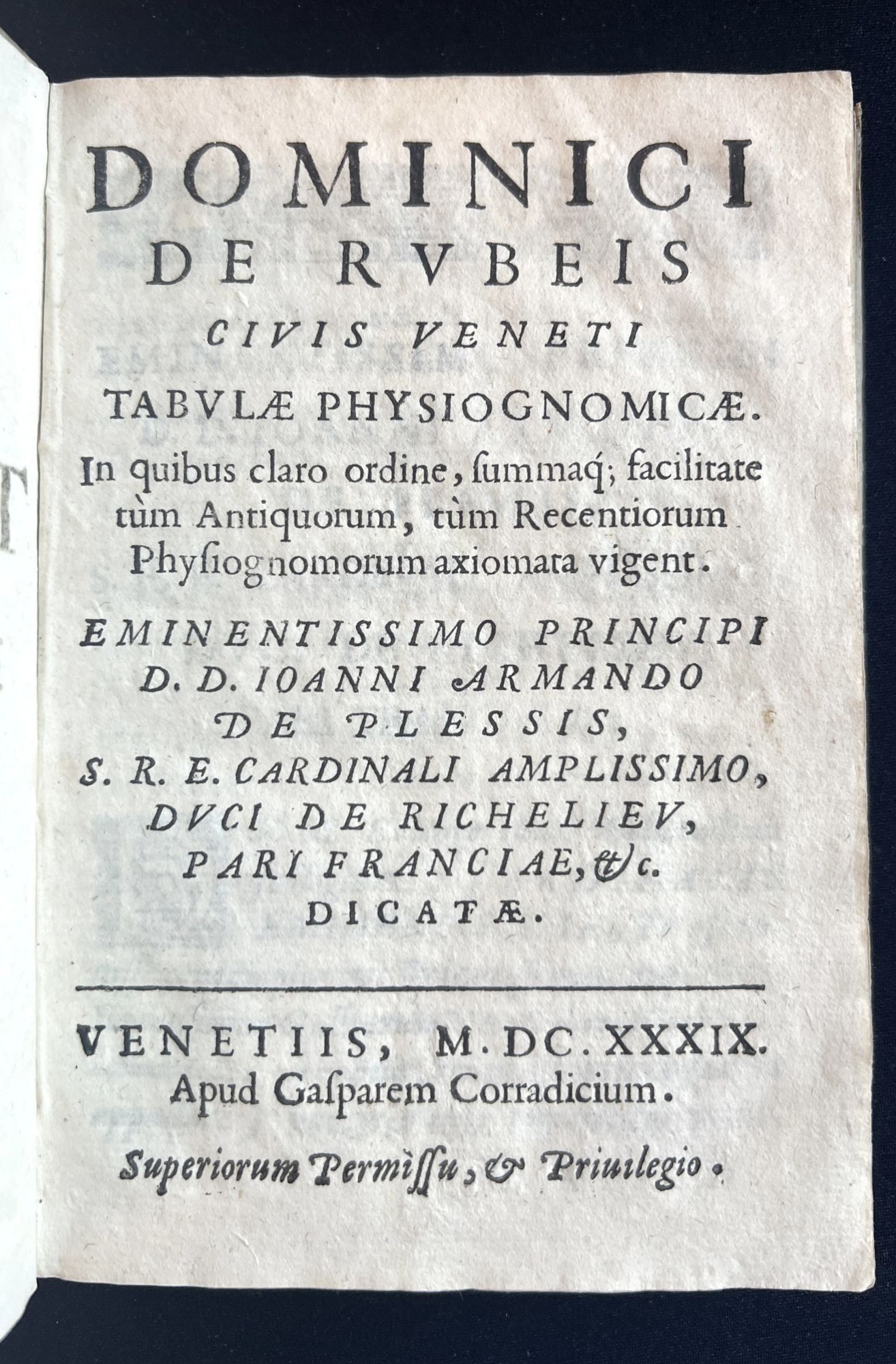

Venice: Gaspare Corradiccio, 1639. 8vo (153 x 104 mm). [8] leaves, the last blank, 144 pp. Half-title. Double column tables throughout, woodcut and typographical ornaments. (Minor wormholes in last leaf.) Contemporary parchment over flexible pasteboards, manuscript title on lower edge (Tabule fisegnomicae [sic]).***

Only Edition of a series of detailed classification tables for the pernicious pseudoscience of physiognomy.

28 body parts or personal physical manifestations are tabulated. Starting from the top and moving outward, different characteristics of the Hair, Forehead, Eyebrows, Eyelashes, Eyes (the longest section), Nose, Nostrils, Cheeks, Mouth, Lips, Teeth, Tongue, Breath, Voice, Laughter, Chin, Beard, Face, Head, Throat, Neck (front and back, collum and cervix), Fingers, Nails, Gait, and Stature (height and weight) are listed in the left-hand columns, with the corresponding meaning in the right-hand columns. A man with bushy eyebrows is sad; one whose eyebrows bend toward his nose is harsh or bitter, big-nosers are foul libidinous liars and traitors, those with slanting eyes are envious, irascible and mendacious, tightly curled hair betrays rudeness and pride, etc. You can see where this leads.

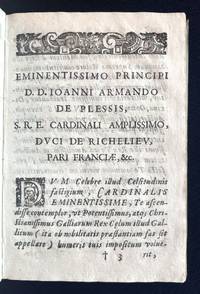

The author (not to be confused with the printer of a later generation) dedicated his tables to the Cardinal de Richelieu, who was interested in the occult sciences. This demonstrates, as notes one modern author (G. Tyler, Physiognomy in the European Novel [1982], p. 41), the prominent and respectable position held by physiognomy in early modern Europe, not surprisingly, since it was such a useful tool for the justification of racism and the “white man’s burden” in this period of expanding colonialism.

The edition has an unusually early half-title: this bibliographical feature did not become common until the eighteenth century (cf. Gaskell, New Introduction to Bibliography [1995], p. 52). That first leaf appears to be omitted from the (incorrect) collation provided by USTC, implying that it is often lacking. OCLC lists 3 US copies (UC San Francisco, Stanford, and Tufts).

USTC 4008959; SBN ITICCUBVEE�42536; cf. Thorndike, History of Magic and Experimental Science (1958), VI, 510 & VIII, 457.

Only Edition of a series of detailed classification tables for the pernicious pseudoscience of physiognomy.

28 body parts or personal physical manifestations are tabulated. Starting from the top and moving outward, different characteristics of the Hair, Forehead, Eyebrows, Eyelashes, Eyes (the longest section), Nose, Nostrils, Cheeks, Mouth, Lips, Teeth, Tongue, Breath, Voice, Laughter, Chin, Beard, Face, Head, Throat, Neck (front and back, collum and cervix), Fingers, Nails, Gait, and Stature (height and weight) are listed in the left-hand columns, with the corresponding meaning in the right-hand columns. A man with bushy eyebrows is sad; one whose eyebrows bend toward his nose is harsh or bitter, big-nosers are foul libidinous liars and traitors, those with slanting eyes are envious, irascible and mendacious, tightly curled hair betrays rudeness and pride, etc. You can see where this leads.

The author (not to be confused with the printer of a later generation) dedicated his tables to the Cardinal de Richelieu, who was interested in the occult sciences. This demonstrates, as notes one modern author (G. Tyler, Physiognomy in the European Novel [1982], p. 41), the prominent and respectable position held by physiognomy in early modern Europe, not surprisingly, since it was such a useful tool for the justification of racism and the “white man’s burden” in this period of expanding colonialism.

The edition has an unusually early half-title: this bibliographical feature did not become common until the eighteenth century (cf. Gaskell, New Introduction to Bibliography [1995], p. 52). That first leaf appears to be omitted from the (incorrect) collation provided by USTC, implying that it is often lacking. OCLC lists 3 US copies (UC San Francisco, Stanford, and Tufts).

USTC 4008959; SBN ITICCUBVEE�42536; cf. Thorndike, History of Magic and Experimental Science (1958), VI, 510 & VIII, 457.