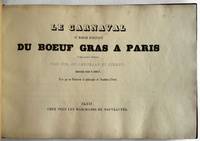

Le Carnaval et Marché Burlesque du Boeuf Gras à Paris

- SIGNED

- Paris: (Schneider & Langrand for) Charles Warré / chez tous les marchands de nouveautés, 1843

Paris: (Schneider & Langrand for) Charles Warré / chez tous les marchands de nouveautés, 1843. Oblong 4to (175 x 262 mm). Collation: 1-104 (fol. 10/4 blank), 75, [7] pages, the pagination including 20 leaves of wood-engravings (printed on rectos only), of which 2 folding plates (counted as 4 pages); all but the fold-out plates included in the collation; the wood engravings by Henri-Désiré Porret after Achille Giroux and Ernest Seigneurgens. (Light foxing to upper margin of title, a couple of tiny marginal chips, else fine.) Late 19th-or early 20th-century half red straight-grained morocco, gilt fillet borders, spine densely gold-tooled in compartments, each with a tiny onlaid dark green morocco lozenge, title gilt in second compartment (by Stroobants); preserving original tan printed wrappers, upper wrapper with title and lithographic vignette (3 riders on a horse). Provenance: Victor Mercier, art nouveau bookplate, collation note dated 26 Feb. 1911 (his collection sold Paris, April-June 1937).***

This little-known masterpiece of Romantic-era wood-engraving is the only edition of a satirical description of the traditional Paris Carnival festival known as the march of the fattened bull, or Boeuf Gras. The quality of Porret’s wood engravings ranks this very rare book with the productions of Daumier, Gavarni and Tony Johannot.

The Boeuf Gras procession, whose roots are ancient (and have been long debated), was traditionally held by the butchers of Paris, who paraded one or more decorated fattened bulls through the streets, disguised as heralds, victims and sacrificers, some sporting their conceptions of Native American headdresses and weapons or Turkish costumes, and others dressed as French and foreign monarchs or officials. A musical band led the procession, and there was much dancing and drinking. At the conclusion of the rowdy parade, which drew enormous crowds, the bulls were traditionally killed and the meat sold to the public. Forbidden during the Revolution, this hugely popular event was resurrected in 1806 and was held almost yearly until 1871. In 1862, Victor Hugo noted that the cortège of the Boeuf Gras was one of the elite groups, "magnificent and joyous," that were allowed to occupy the center of the boulevard during the Carnival procession (Les Misérables, Gallimard, 2017, p. 1176).

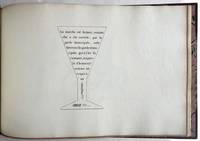

An unidentified writer (described on the title as a philosophy professor from the Academy of Yvetot) penned the present text, a blow-by-blow description of the procession. Filled with digressions, dialogues, poems, and word-play, the many contemporary references of this comic text mock politicians, civil servants, plays, journals, other illustrators, fashions, and various real and fictional Parisian characters (including those of the wildly successful satirical play Robert Macaire). An entire page of ellipses, footnoted “the wittiest page of this album,” precedes the conclusion, on the following page, whose words are enclosed in fillets in the shape of a wine glass.

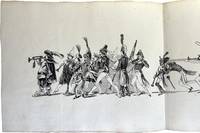

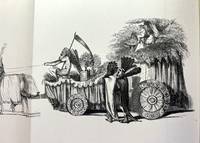

But the text serves above all to accompany the illustrations. Opening with neatly helmeted soldiers astride prancing horses, the wood-engravings, centered within large white margins, move through the procession both spatially and temporally, as the parade gradually degrades into fights and chaos. The folding plates portray the motley band of musicians and a horse-drawn float with skinny Father Time. A fat and somber bull, led by two muscular club-carrying grooms, appears alone on a page. One of the last illustrations shows the surging crowd of onlookers, blowing noisemakers and trampling each other in their haste to see the fun, and fading into a long trail of people that snakes up the page. The artists’ dynamic drawings, showing the propulsion of the parade and the internal squabbles of its participants, are beautifully rendered by the now largely forgotten Porret. Called by Beraldi “one of the most famous names of French wood-engraving in the 19th century, and perhaps even the best-known name and the most highly esteemed by bibliophiles!” (Graveurs XI: 24), Porret received barely a mention, and then only as one in a list of top engravers, in Ray’s Art of the French Illustrated Book (v. II: 248). That he was a selling point at the time is evident from the prominence given his name on the titles. (The wrapper title differs slightly from the title-page: the imprint names the publisher Warée and supplies Giroux’s first name. I have seen another copy with a variant wrapper, differently illustrated.)

[NB: racist caricatures] Many of the disguises include feathered headgear à la Native American, and a couple of masked characters are caricatures of Black Africans; another mask is that of an Arab or Turk. But, while the carnival concept of the world turned upside down included racist tropes, the tacitly implied superiority of the men and women here disguised as so-called “savages” is in fact mocked (along with everything else) by the author of the text.

I locate one N. American institutional copy, at Toronto. Not in the Gordon Ray collection at the Morgan Library.

Sander, Die illustrierten französischen Bücher des 19. Jahrhunderts 140; Vicaire, Manuel, II: 116; Beraldi, Les Graveurs du XIXe Siècle 11: 29 (variant title: “Texte par deux gants blancs”).

This little-known masterpiece of Romantic-era wood-engraving is the only edition of a satirical description of the traditional Paris Carnival festival known as the march of the fattened bull, or Boeuf Gras. The quality of Porret’s wood engravings ranks this very rare book with the productions of Daumier, Gavarni and Tony Johannot.

The Boeuf Gras procession, whose roots are ancient (and have been long debated), was traditionally held by the butchers of Paris, who paraded one or more decorated fattened bulls through the streets, disguised as heralds, victims and sacrificers, some sporting their conceptions of Native American headdresses and weapons or Turkish costumes, and others dressed as French and foreign monarchs or officials. A musical band led the procession, and there was much dancing and drinking. At the conclusion of the rowdy parade, which drew enormous crowds, the bulls were traditionally killed and the meat sold to the public. Forbidden during the Revolution, this hugely popular event was resurrected in 1806 and was held almost yearly until 1871. In 1862, Victor Hugo noted that the cortège of the Boeuf Gras was one of the elite groups, "magnificent and joyous," that were allowed to occupy the center of the boulevard during the Carnival procession (Les Misérables, Gallimard, 2017, p. 1176).

An unidentified writer (described on the title as a philosophy professor from the Academy of Yvetot) penned the present text, a blow-by-blow description of the procession. Filled with digressions, dialogues, poems, and word-play, the many contemporary references of this comic text mock politicians, civil servants, plays, journals, other illustrators, fashions, and various real and fictional Parisian characters (including those of the wildly successful satirical play Robert Macaire). An entire page of ellipses, footnoted “the wittiest page of this album,” precedes the conclusion, on the following page, whose words are enclosed in fillets in the shape of a wine glass.

But the text serves above all to accompany the illustrations. Opening with neatly helmeted soldiers astride prancing horses, the wood-engravings, centered within large white margins, move through the procession both spatially and temporally, as the parade gradually degrades into fights and chaos. The folding plates portray the motley band of musicians and a horse-drawn float with skinny Father Time. A fat and somber bull, led by two muscular club-carrying grooms, appears alone on a page. One of the last illustrations shows the surging crowd of onlookers, blowing noisemakers and trampling each other in their haste to see the fun, and fading into a long trail of people that snakes up the page. The artists’ dynamic drawings, showing the propulsion of the parade and the internal squabbles of its participants, are beautifully rendered by the now largely forgotten Porret. Called by Beraldi “one of the most famous names of French wood-engraving in the 19th century, and perhaps even the best-known name and the most highly esteemed by bibliophiles!” (Graveurs XI: 24), Porret received barely a mention, and then only as one in a list of top engravers, in Ray’s Art of the French Illustrated Book (v. II: 248). That he was a selling point at the time is evident from the prominence given his name on the titles. (The wrapper title differs slightly from the title-page: the imprint names the publisher Warée and supplies Giroux’s first name. I have seen another copy with a variant wrapper, differently illustrated.)

[NB: racist caricatures] Many of the disguises include feathered headgear à la Native American, and a couple of masked characters are caricatures of Black Africans; another mask is that of an Arab or Turk. But, while the carnival concept of the world turned upside down included racist tropes, the tacitly implied superiority of the men and women here disguised as so-called “savages” is in fact mocked (along with everything else) by the author of the text.

I locate one N. American institutional copy, at Toronto. Not in the Gordon Ray collection at the Morgan Library.

Sander, Die illustrierten französischen Bücher des 19. Jahrhunderts 140; Vicaire, Manuel, II: 116; Beraldi, Les Graveurs du XIXe Siècle 11: 29 (variant title: “Texte par deux gants blancs”).