Archive of Chilean Diplomat and UN Officer Benjamin Alberto Cohen, 1948–1958

- Approximately 190 items: eighty-five typed copies of letters (not including duplicates), forty-four of which contain the origina

- United States, South America, Europe, and Africa , 1972

United States, South America, Europe, and Africa, 1972. Approximately 190 items: eighty-five typed copies of letters (not including duplicates), forty-four of which contain the original handwritten letter as well; four photographs and fourteen negatives; thirty-one telegrams; fifty copies of UN Latin American radio transcripts; and nine pieces of ephemera. Overall excellent.. Benjamin Alberto Cohen (1896–1960) was born in Concepción, Chile, to Lithuanian Jewish parents. He began his career as a journalist, then served in various positions in the Chilean legation and Chilean Foreign Office, including as Ambassadorships to Bolivia and Venezuela. In 1945, he began his career with the UN as part of the executive secretariat of the Preparatory Commission. He would serve with the Department of Public Information and Trusteeship Council, and ended his career as an ambassador in the Chilean delegation to the UN.[1] Cohen married his second wife, Rita Mayer Cohen (1925–1992), in 1948; the two met while Mayer was on staff at the UN in New York City.

Offered here is an archive of Cohen’s documents, mainly letters to Mayer and transcripts of episodes of “Hablemos de las Naciones Unidas”, a Spanish-language radio broadcast for the Latin American Service Radio Division, mostly authored by Cohen. Mayer typed copies of Cohen’s handwritten letters for the couple’s children following his death; more than half of the typed copies in this archive include the original letter as well (note that there are occasionally multiple typed copies; the inventory only lists the number of unique letters).

Mayer did not censor Cohen’s letters, remarking in a draft of a note to her children that “Hopefully you are old enough to understand that he too had human weaknesses along with his extraordinary strengths”—they occasionally deal with marital issues between the two. However, they are mostly records of Cohen’s world travels and extremely busy social and work schedule; his obituary comments that he was “known, admired and personally liked by hundreds of diplomats and journalists.”[1] For instance, Cohen writes from Santiago, Chile:

“The following morning I again had a constant stream of visitors and more telephone calls – many from dear Bolivian friends who are now political exiles – until I had to leave for lunch at the Chilean Embassy, where I saw every Chief of diplomatic mission and senior Foreign Office officials plus the Vice-President of Peru and important political figures who were attending a farewell to the Venezuelan Ambassador.” (August 17, 1952)

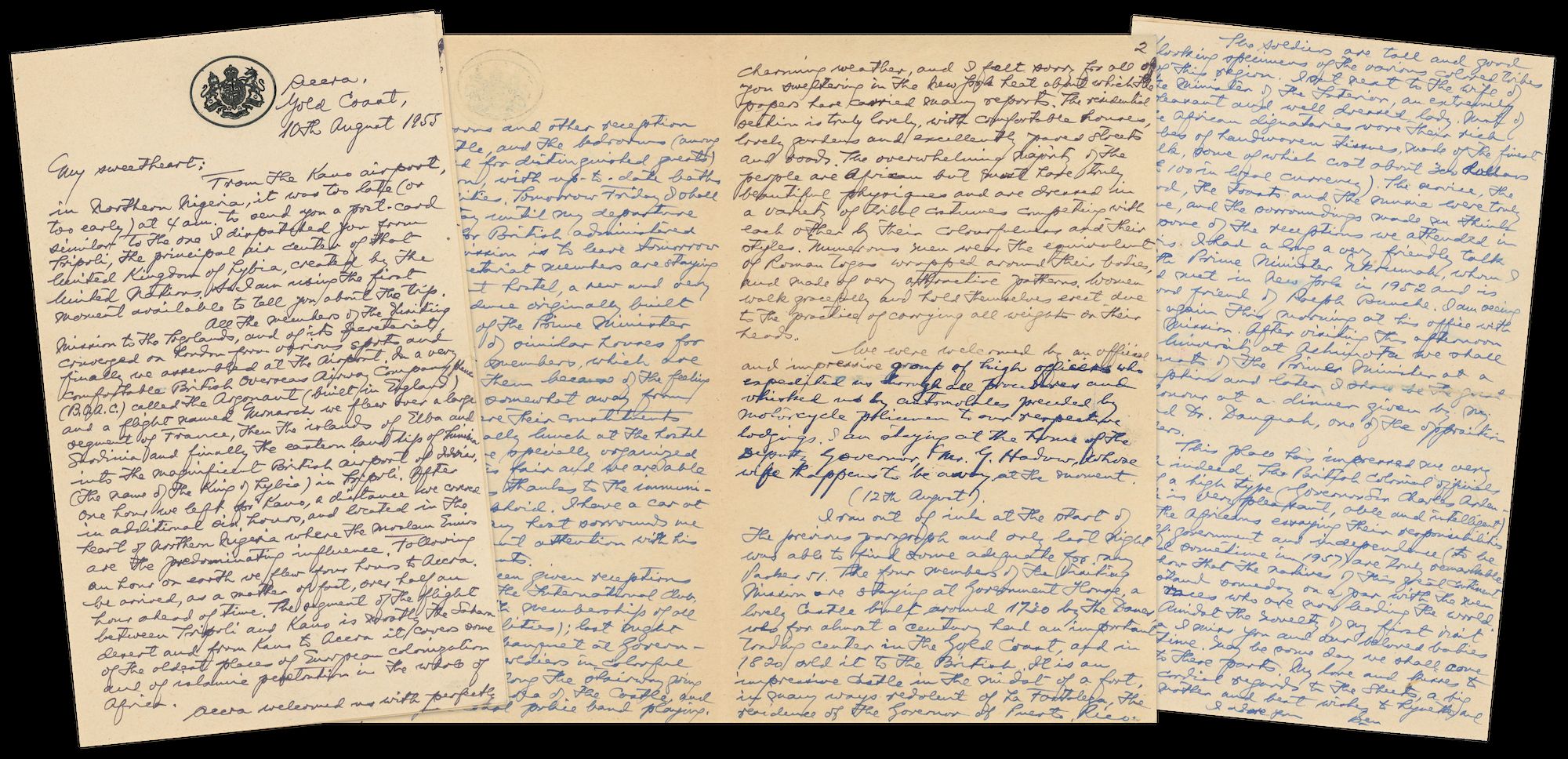

His letters are often inventories of where he dined and with whom, from Chilean senator Miguel Cruchaga Tocornal to Danish film director and producer Mogens Skot-Hansen to UNESCO Director-General Luther Evans, among innumerable others. However, his 1955 and 1956 letters from tours of Africa are by far the most detailed. He writes from Accra, the capital of what was then the British colony of Gold Coast and is now Ghana:

“We have been given receptions (by the Governor and the International Club, an organization with membership of all races and nationalities); last night we had a solemn banquet at Government house, with soldiers in colorful uniforms lined along the stairway going up to the reception area of the Castle, and the famous Gold Coast police band playing. The soldiers are tall and good looking specimens of the various colored tribes of this region. Most of the African dignitaries wore their rich robes of handwoven tissues, made of the finest silk [...] I had a long and very friendly talk with Prime Minister [Kwame] Nkrumah, whom I had met in New York in 1952 and is a good friend of Ralph Bunche. I am seeing him again this morning at his office with the Mission [...] later I shall be the guest of honour at a dinner given by my friend Dr. [Joseph Boakye] Danquah, one of the opposition leaders. This place has impressed me very much indeed. The British Colonial officials are of a high type [...] and the Africans assaying their responsibilities for self-government and independence (to be secured sometime in 1957) are truly remarkable and show that the natives of this great continent will stand someday on a par with the other races who are now leading the world.” (August 10, 1955)

From Lomé in then-French Togoland, he describes the attitudes of French versus English colonists in Africa (August 18), and recounts a trip to visit the current Aného royalty:

“In a very old house, comprised of rooms looking onto successive patios, separated by their respective doors, two elderly gentlemen, followed by many others, welcomed me to the royal residence of the Anecho kings. [...] We were ushered into a living room furnished with very bourgeois furniture now fashionable in Africa, with numerous tables sporting lovely French scarves as coverings and one a bigger one with the portraits of Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh sold by the thousands throughout British territories everywhere. Against one of the walls was the royal throne, a chair redolent of those used in churches where the clergy sit [...] On the back it bore an inscription memorializing the last monarch who ever sat on it. On the walls around the room diplomas of certain French decorations like the Legion of Honor, the Order of the Black Star or that of Agricultural Merit received by the late lamented king whose family name contained, to my utter amazement, those of Lawson and others strongly British [...] When we arrived at the Chief’s residence we were welcomed by him in person, accompanied by a few of his family and subjects.” (August 19, 1955)

The next year Cohen traveled through Johannesburg and Cape Town, South Africa; Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania); Usumbura, Ruanda-Urundi (now Bujumbura, Burundi); and a number of others cities; visiting with figures including Aly Khan and Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi. He spends the most time by far with Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. He first met Selassie in Addis Ababa—Selassie is “most charming and friendly and I believe that our exchange of views will prove very useful in the solution of certain problems” (May 7)—and then again at an event at the Fasil Ghebbi. He describes the event:

“One arrived at the foot of a stone stairway lined with soldiers wearing a most unusual military uniform but with a sort of barbaric beauty. Crimson long trousers and blouse, over which is worn a sort of tunic with four long ends that fall down to the knees and look like strips of lion hide. The headgear is like a tube made of the same material with a silver colored string surrounding the center part and the whole topped with long strands of lion hair. [...] At the top platform the Chiefs of Protocol of the Palace and of the Foreign Office welcomed the guests. [...] At the very end [of the reception hall], under a crimson and gold canopy, on a raised dais, sat the Emperor and Empress, surrounded by the Princes and dukes, with two tall personages in gold embroidered tunics directly behind the Emperor. These are supposed to be the traditional ‘false Emperors’ who must assume any risks or dangers threatening the person of their lord and master. Each individual or couple, when called upon by the Chief of Protocol, would advance to the entrance, make a bow and after a few steps bow again. Following a third bow they would approach their Imperial Majesties and shake hands with them.” (May 9, 1956)

After dinner,

“the Private Secretary and Principal Advisor to the Emperor asked me to approach [the] dais because the Emperor wanted to converse with me. I sat next to him, at a lower level, and to the utter amazement of foreign diplomats and Ethiopians, spent the next half hour in conversation with the Monarch who is, as you know, a very dynamic and interesting man. He was most charming throughout, and we discussed several important matters.”

We exclude much more of Cohen’s descriptions of Africa for the sake of space; they are the most extensive in his letters. In 1958, Cohen touches on July’s near-uprising in Venezuela, and violence in the leadup to the presidential election in Chile.

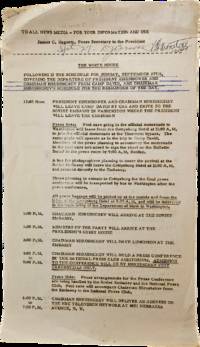

The photographs in the archive are mainly family photos, with one of Cohen’s headstone in Chile. The collection of telegrams are condolences sent to Mayer on Cohen’s death. Interesting ephemera include invitations and a flag for the commissioning ceremony of the Brazilian cruiser Tamandaré and a press schedule for the final day of Nikita Khrushchev’s 1957 visit to Camp David.

Of interest to historians of the UN and diplomacy in South America, and of the early and pre-decolonial period in Africa.

[1] “Benjamin Cohen Of The U.N. Dead”, The New York Times, March 13, 1960, 86.

Offered here is an archive of Cohen’s documents, mainly letters to Mayer and transcripts of episodes of “Hablemos de las Naciones Unidas”, a Spanish-language radio broadcast for the Latin American Service Radio Division, mostly authored by Cohen. Mayer typed copies of Cohen’s handwritten letters for the couple’s children following his death; more than half of the typed copies in this archive include the original letter as well (note that there are occasionally multiple typed copies; the inventory only lists the number of unique letters).

Mayer did not censor Cohen’s letters, remarking in a draft of a note to her children that “Hopefully you are old enough to understand that he too had human weaknesses along with his extraordinary strengths”—they occasionally deal with marital issues between the two. However, they are mostly records of Cohen’s world travels and extremely busy social and work schedule; his obituary comments that he was “known, admired and personally liked by hundreds of diplomats and journalists.”[1] For instance, Cohen writes from Santiago, Chile:

“The following morning I again had a constant stream of visitors and more telephone calls – many from dear Bolivian friends who are now political exiles – until I had to leave for lunch at the Chilean Embassy, where I saw every Chief of diplomatic mission and senior Foreign Office officials plus the Vice-President of Peru and important political figures who were attending a farewell to the Venezuelan Ambassador.” (August 17, 1952)

His letters are often inventories of where he dined and with whom, from Chilean senator Miguel Cruchaga Tocornal to Danish film director and producer Mogens Skot-Hansen to UNESCO Director-General Luther Evans, among innumerable others. However, his 1955 and 1956 letters from tours of Africa are by far the most detailed. He writes from Accra, the capital of what was then the British colony of Gold Coast and is now Ghana:

“We have been given receptions (by the Governor and the International Club, an organization with membership of all races and nationalities); last night we had a solemn banquet at Government house, with soldiers in colorful uniforms lined along the stairway going up to the reception area of the Castle, and the famous Gold Coast police band playing. The soldiers are tall and good looking specimens of the various colored tribes of this region. Most of the African dignitaries wore their rich robes of handwoven tissues, made of the finest silk [...] I had a long and very friendly talk with Prime Minister [Kwame] Nkrumah, whom I had met in New York in 1952 and is a good friend of Ralph Bunche. I am seeing him again this morning at his office with the Mission [...] later I shall be the guest of honour at a dinner given by my friend Dr. [Joseph Boakye] Danquah, one of the opposition leaders. This place has impressed me very much indeed. The British Colonial officials are of a high type [...] and the Africans assaying their responsibilities for self-government and independence (to be secured sometime in 1957) are truly remarkable and show that the natives of this great continent will stand someday on a par with the other races who are now leading the world.” (August 10, 1955)

From Lomé in then-French Togoland, he describes the attitudes of French versus English colonists in Africa (August 18), and recounts a trip to visit the current Aného royalty:

“In a very old house, comprised of rooms looking onto successive patios, separated by their respective doors, two elderly gentlemen, followed by many others, welcomed me to the royal residence of the Anecho kings. [...] We were ushered into a living room furnished with very bourgeois furniture now fashionable in Africa, with numerous tables sporting lovely French scarves as coverings and one a bigger one with the portraits of Queen Elizabeth and the Duke of Edinburgh sold by the thousands throughout British territories everywhere. Against one of the walls was the royal throne, a chair redolent of those used in churches where the clergy sit [...] On the back it bore an inscription memorializing the last monarch who ever sat on it. On the walls around the room diplomas of certain French decorations like the Legion of Honor, the Order of the Black Star or that of Agricultural Merit received by the late lamented king whose family name contained, to my utter amazement, those of Lawson and others strongly British [...] When we arrived at the Chief’s residence we were welcomed by him in person, accompanied by a few of his family and subjects.” (August 19, 1955)

The next year Cohen traveled through Johannesburg and Cape Town, South Africa; Dar es Salaam, Tanganyika (now Tanzania); Usumbura, Ruanda-Urundi (now Bujumbura, Burundi); and a number of others cities; visiting with figures including Aly Khan and Abdul Rahman al-Mahdi. He spends the most time by far with Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie. He first met Selassie in Addis Ababa—Selassie is “most charming and friendly and I believe that our exchange of views will prove very useful in the solution of certain problems” (May 7)—and then again at an event at the Fasil Ghebbi. He describes the event:

“One arrived at the foot of a stone stairway lined with soldiers wearing a most unusual military uniform but with a sort of barbaric beauty. Crimson long trousers and blouse, over which is worn a sort of tunic with four long ends that fall down to the knees and look like strips of lion hide. The headgear is like a tube made of the same material with a silver colored string surrounding the center part and the whole topped with long strands of lion hair. [...] At the top platform the Chiefs of Protocol of the Palace and of the Foreign Office welcomed the guests. [...] At the very end [of the reception hall], under a crimson and gold canopy, on a raised dais, sat the Emperor and Empress, surrounded by the Princes and dukes, with two tall personages in gold embroidered tunics directly behind the Emperor. These are supposed to be the traditional ‘false Emperors’ who must assume any risks or dangers threatening the person of their lord and master. Each individual or couple, when called upon by the Chief of Protocol, would advance to the entrance, make a bow and after a few steps bow again. Following a third bow they would approach their Imperial Majesties and shake hands with them.” (May 9, 1956)

After dinner,

“the Private Secretary and Principal Advisor to the Emperor asked me to approach [the] dais because the Emperor wanted to converse with me. I sat next to him, at a lower level, and to the utter amazement of foreign diplomats and Ethiopians, spent the next half hour in conversation with the Monarch who is, as you know, a very dynamic and interesting man. He was most charming throughout, and we discussed several important matters.”

We exclude much more of Cohen’s descriptions of Africa for the sake of space; they are the most extensive in his letters. In 1958, Cohen touches on July’s near-uprising in Venezuela, and violence in the leadup to the presidential election in Chile.

The photographs in the archive are mainly family photos, with one of Cohen’s headstone in Chile. The collection of telegrams are condolences sent to Mayer on Cohen’s death. Interesting ephemera include invitations and a flag for the commissioning ceremony of the Brazilian cruiser Tamandaré and a press schedule for the final day of Nikita Khrushchev’s 1957 visit to Camp David.

Of interest to historians of the UN and diplomacy in South America, and of the early and pre-decolonial period in Africa.

[1] “Benjamin Cohen Of The U.N. Dead”, The New York Times, March 13, 1960, 86.