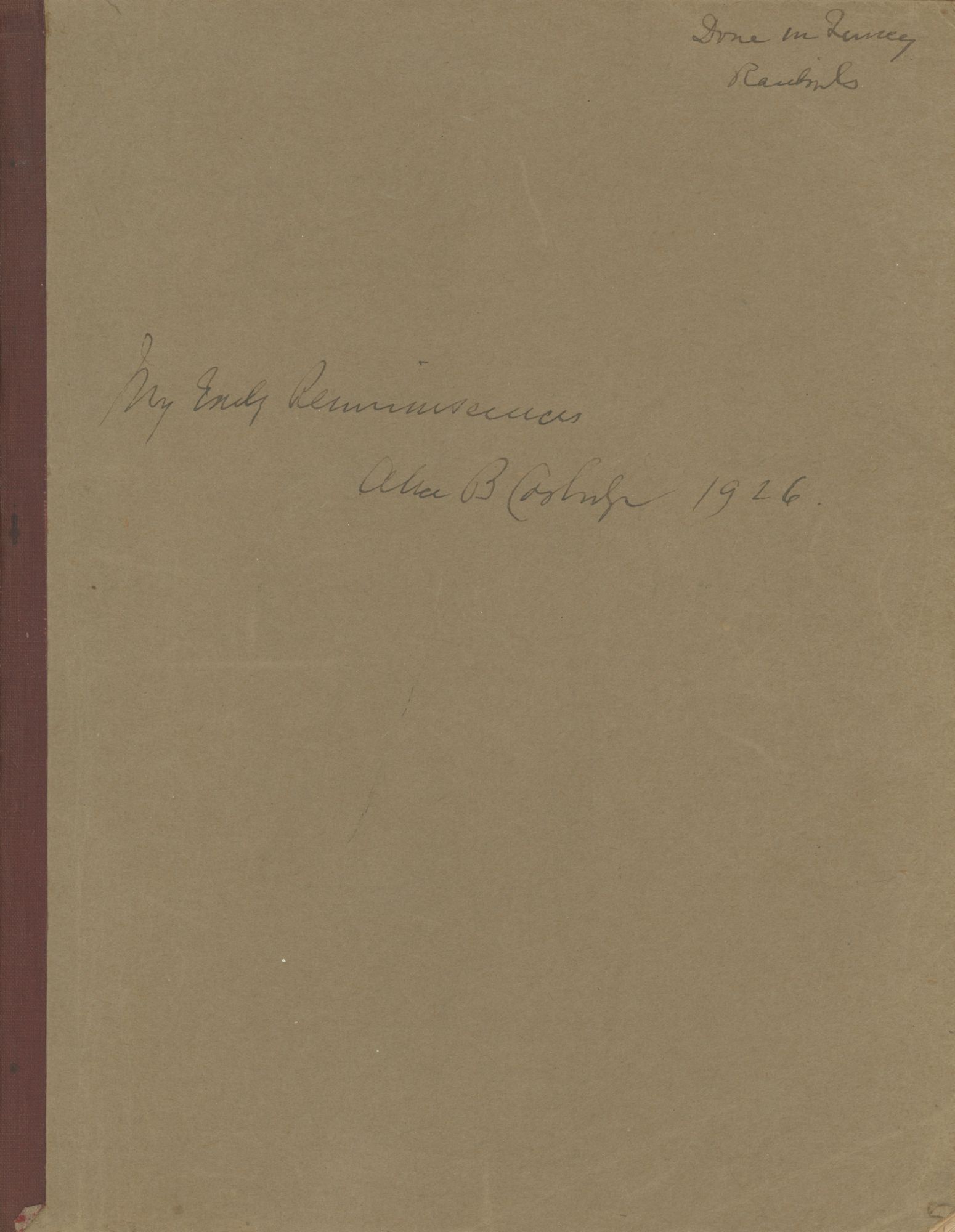

My Early Reminiscences / Alice B Coolidge 1926

- 201 pp, cardstock wraps

- Quincy, Massachusetts: unpublished, 1926

Quincy, Massachusetts: unpublished, 1926. 201 pp, cardstock wraps. Normal wear to wraps; overall Near Fine.. Alice Brackett (White) Coolidge (1864–1927) was a Boston socialite of the prominent Richardson family; her grandfather was merchant and Massachusetts State Legislator Jeffrey Richardson. Coolidge was also the author of three children’s books: The Bunnies of Evergreen Village (1917), The Refugees in Evergreen Village (1918), and Evergreen Village to the Rescue (1922). Offered here is Coolidge’s unpublished memoir of her early life written in 1926, titled My Early Reminiscences.

The memoir recalls Coolidge’s childhood and teen years spent mainly in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine. Her recollections typically involve extensive descriptions of the houses at which her family stayed, the scenery around them, and the various families they met and visited with. Given her position in society, her acquaintances are sometimes quite influential people: Princeton president John Grier Hibben enjoys Coolidge’s fishcakes; Trinity Church rector Phillips Brooks gives her grandfather an “excellent pew” in the newly-finished church; pioneering doctor Alfred Worcester mistakes red pepper for mercury in a scientific demonstration at her school; and she recalls brief correspondences with John Greenleaf Whittier and William James.

Coolidge also took dance lessons from Augustus Papanti, whom she describes as “one of the thinnest men I ever saw” who was “very melancholy. I hardly remember his ever smiling”; and remembers Judge Charles Devens for “his great stature, his charming face, his courtliness of manner and his really boyish simplicity in entering into our evening games”, including a game of “mind reading” which Devens played “with zest.”

One of her longtime friends was Rear Admiral John E. Pillsbury. She recalls:

“Mr. Pillsbury as a young naval man, a brother-in-law of my uncle, Dr. Richardson, used to take me out in the swan-boats on the Public Garden Pond. Later he went through all the ranks up to being retired as a Rear Admiral, but time and circumstances never changed him. We always met at Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners, and always talked at great length. [...] He was a wonderfully interesting, lovable man, and very modest and unassuming and shy. I always considered him one of my best friends, though older by many years than I.”

Another interesting New England figure Coolidge encountered was Joseph Lee. She describes Lee’s hotel in Newton:

“The house where we stayed was kept by a remarkable man named Joseph Lee. He was a mulatto, much above many of his kind, and his wife was a handsome woman, partly Indian. They did the cooking and he waited on table with a colored maid to help him. In fact there were no white women in the house. The cooking was delicious.”

Lee was born enslaved in South Carolina, freed in 1865, and went on to invent the automatic bread kneading and bread crumbing machines.

Though nearly all of her childhood was spent in New England, she also remembers being invited to visit Charles Joseph Bonaparte in Baltimore:

“We had never been so far south except to Washington, and I felt a curious feeling of being in a different atmosphere from any I had known. [...] We were met at the station by Mrs. Bonaparte in a large, roomy covered vehicle with two horses. The coachman and footman were in the Bonaparte colors -- a deep wine color. The footman I well remember. He was a light-colored young negro, very handsome and smiling and excited over having young ladies from the North. [...] All the servants were colored, and lived in cabins near the house. [...] I never knew [Mr. Bonaparte] in public life, so my memories of him are quite intimate and I fancy I saw much of his real self. [...] His mind was very active. He used to talk or listen as he walked and he moved his head in a curious way from one side to the other with a slightly rolling motion, which was distinctly individual. [...] I never saw him irritated or excited, and he was always very simple. In the group picture we had taken at the Maplewood, he sat down cross-legged on the piazza floor like a boy. That was in about 1887. I suppose in public life or in law he was different, but he was very equable and charming as we met him in his home and at the mountains. Most of all I admired his sweet tender ways with his flower-like wife.”

This was not too long after the end of Reconstruction, and Coolidge remarks on the tense atmosphere:

“Mrs. Bonaparte had warned me to be careful about questions regarding the North and South, as the ‘feeling’ had not yet died away. I was so glad she had warned me. A gentleman slipped in and sat down beside me [to watch a parade] and whispered in my ear as the bands had been playing ‘Dixie’ how glad he was to meet a Northerner. I was glad to meet him, too, although I remember neither his name nor face, but I felt I breathed freer in his sympathetic locality. [...] I had no idea that this feeling still remained as far North as Baltimore, and of course I remembered how our Massachusetts troops had been fired upon in Baltimore at the outset of the war, but I was admonished and very wise and only returned my unremembered neighbor’s greeting with a sympathetic word and look.”

Besides individuals, Coolidge does cover a few historical events, including the Great Boston Fire of 1872:

“Oh! a horrible sight met our eyes. Back of the opposite houses in Park Square was a background of sheets of red flames and heavy black smoke rising high into the air. [...] On the Parade Ground all was in confusion and the sight was very sad and never-to-be-forgotten. It was literally covered with boxes and bales of furniture and sad forlorn desperate looking people crouching or sitting or standing amidst what they had saved from their homes [...] At night [...] the whole city was in darkness, as there was no gas.”

The family also frequently stayed at hotels in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and Coolidge recalls the “overwhelmingly tragic” effects of the 1867 sale of this land to logging companies; she writes that, looking out from the Flume House in Franconia, “all about were brown scarred places marking the woodchoppers’ work which was cutting away our beautiful trees for lumber”.

In this memoir, Coolidge supplies detailed remembrances of the private personalities of influential figures of Gilded Age New England. We find two copies of My Early Reminiscences on OCLC. Of interest to historians of the era, especially as told through the perspective of a young woman.

The memoir recalls Coolidge’s childhood and teen years spent mainly in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine. Her recollections typically involve extensive descriptions of the houses at which her family stayed, the scenery around them, and the various families they met and visited with. Given her position in society, her acquaintances are sometimes quite influential people: Princeton president John Grier Hibben enjoys Coolidge’s fishcakes; Trinity Church rector Phillips Brooks gives her grandfather an “excellent pew” in the newly-finished church; pioneering doctor Alfred Worcester mistakes red pepper for mercury in a scientific demonstration at her school; and she recalls brief correspondences with John Greenleaf Whittier and William James.

Coolidge also took dance lessons from Augustus Papanti, whom she describes as “one of the thinnest men I ever saw” who was “very melancholy. I hardly remember his ever smiling”; and remembers Judge Charles Devens for “his great stature, his charming face, his courtliness of manner and his really boyish simplicity in entering into our evening games”, including a game of “mind reading” which Devens played “with zest.”

One of her longtime friends was Rear Admiral John E. Pillsbury. She recalls:

“Mr. Pillsbury as a young naval man, a brother-in-law of my uncle, Dr. Richardson, used to take me out in the swan-boats on the Public Garden Pond. Later he went through all the ranks up to being retired as a Rear Admiral, but time and circumstances never changed him. We always met at Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners, and always talked at great length. [...] He was a wonderfully interesting, lovable man, and very modest and unassuming and shy. I always considered him one of my best friends, though older by many years than I.”

Another interesting New England figure Coolidge encountered was Joseph Lee. She describes Lee’s hotel in Newton:

“The house where we stayed was kept by a remarkable man named Joseph Lee. He was a mulatto, much above many of his kind, and his wife was a handsome woman, partly Indian. They did the cooking and he waited on table with a colored maid to help him. In fact there were no white women in the house. The cooking was delicious.”

Lee was born enslaved in South Carolina, freed in 1865, and went on to invent the automatic bread kneading and bread crumbing machines.

Though nearly all of her childhood was spent in New England, she also remembers being invited to visit Charles Joseph Bonaparte in Baltimore:

“We had never been so far south except to Washington, and I felt a curious feeling of being in a different atmosphere from any I had known. [...] We were met at the station by Mrs. Bonaparte in a large, roomy covered vehicle with two horses. The coachman and footman were in the Bonaparte colors -- a deep wine color. The footman I well remember. He was a light-colored young negro, very handsome and smiling and excited over having young ladies from the North. [...] All the servants were colored, and lived in cabins near the house. [...] I never knew [Mr. Bonaparte] in public life, so my memories of him are quite intimate and I fancy I saw much of his real self. [...] His mind was very active. He used to talk or listen as he walked and he moved his head in a curious way from one side to the other with a slightly rolling motion, which was distinctly individual. [...] I never saw him irritated or excited, and he was always very simple. In the group picture we had taken at the Maplewood, he sat down cross-legged on the piazza floor like a boy. That was in about 1887. I suppose in public life or in law he was different, but he was very equable and charming as we met him in his home and at the mountains. Most of all I admired his sweet tender ways with his flower-like wife.”

This was not too long after the end of Reconstruction, and Coolidge remarks on the tense atmosphere:

“Mrs. Bonaparte had warned me to be careful about questions regarding the North and South, as the ‘feeling’ had not yet died away. I was so glad she had warned me. A gentleman slipped in and sat down beside me [to watch a parade] and whispered in my ear as the bands had been playing ‘Dixie’ how glad he was to meet a Northerner. I was glad to meet him, too, although I remember neither his name nor face, but I felt I breathed freer in his sympathetic locality. [...] I had no idea that this feeling still remained as far North as Baltimore, and of course I remembered how our Massachusetts troops had been fired upon in Baltimore at the outset of the war, but I was admonished and very wise and only returned my unremembered neighbor’s greeting with a sympathetic word and look.”

Besides individuals, Coolidge does cover a few historical events, including the Great Boston Fire of 1872:

“Oh! a horrible sight met our eyes. Back of the opposite houses in Park Square was a background of sheets of red flames and heavy black smoke rising high into the air. [...] On the Parade Ground all was in confusion and the sight was very sad and never-to-be-forgotten. It was literally covered with boxes and bales of furniture and sad forlorn desperate looking people crouching or sitting or standing amidst what they had saved from their homes [...] At night [...] the whole city was in darkness, as there was no gas.”

The family also frequently stayed at hotels in the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and Coolidge recalls the “overwhelmingly tragic” effects of the 1867 sale of this land to logging companies; she writes that, looking out from the Flume House in Franconia, “all about were brown scarred places marking the woodchoppers’ work which was cutting away our beautiful trees for lumber”.

In this memoir, Coolidge supplies detailed remembrances of the private personalities of influential figures of Gilded Age New England. We find two copies of My Early Reminiscences on OCLC. Of interest to historians of the era, especially as told through the perspective of a young woman.