Le relationi vniuersali di Giouanni Botero benese, diuise in sette parti. Alle quali vi sono aggiunte nuouamente i Capitani dell'istesso auttore, con le Relationi di Spagna; del Stato della Chiesa, & di Sauoia. Nella prima parte, si contiene la descrittione dell'Europa, dell'Asia, e dell'Africa ... Nella seconda, si dà contezza de' maggiori prencipi del mondo ... Nella terza, si tratta ancor de' popoli d'ogni credenza ... Nella quarta, si tratta delle superstitioni in che viueuano già le genti del Mondo nuouo ..

- SIGNED Hardcover

- Venice: Appresso Alessandro Vecchi, 1618

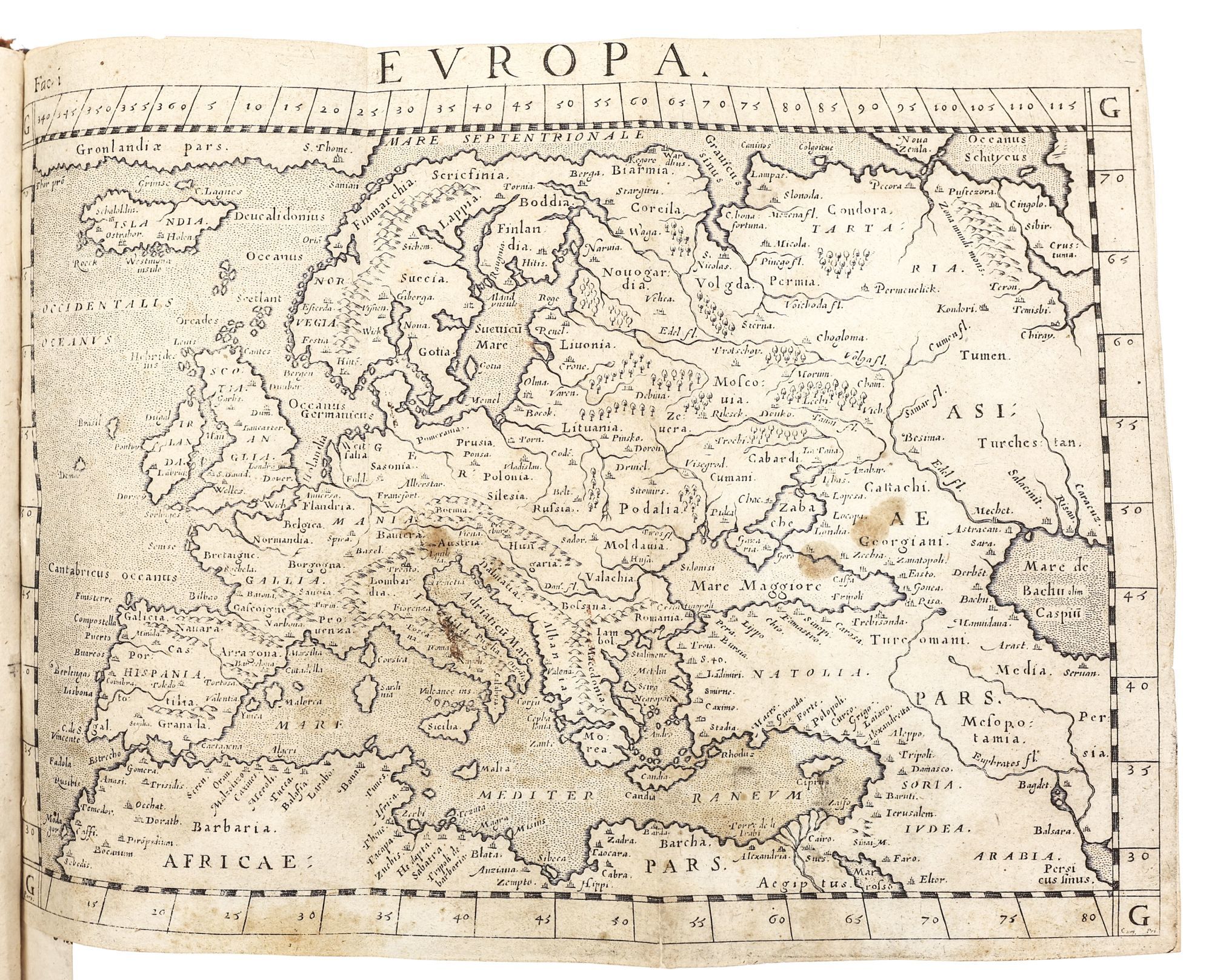

Venice: Appresso Alessandro Vecchi, 1618. FIRST EDITION WITH THE WOODCUTS. The first book had been published in 1591, with Parts II and III appearing in 1592 and 1595. The first collective edition, with all four Parts and the four maps, was published at Bergamo in 1596. This 1618 edition is the first to include the second part of Part IV (the “Aggiunta”), in which the woodcuts are to be found. Hardcover. Fine. Bound in 18th c. speckled boards with leather spine with gilt ornaments in the compartments and a citron Morocco label, also gilt (corners bumped, some wear to extremities, repairs at head and foot of spine, mild discoloring to paper where it is laid over the calf. A very good copy with minor faults: text-block cut a bit short at the head, occasionally affecting the headline; title lightly soiled and with early signature washed out; small tear in inner margin of leaf B8; light stains on map of Europe; repaired split in one fold of the Asia map (affecting the image very slightly) and the same to the map of Africa. Map of the Americas trimmed just within the rule at the foot; small hole in leaf A3 of Part II, affecting a few letters; natural paper flaws to blank corners of a few leaves. In Part II, sections of text on leaves a3-4 are scored through in ink; there are two small worm-tracks in text of the same leaf. The woodcuts on lvs. D4 and D7 (in Pt. 4.b) are slightly shaved. Illustrated with 30 full-page and 2 half-page woodcuts of monsters and indigenous peoples, attributed to Hans Burgkmair (see below); and four folding maps (Europe, Asia, Africa, and The Americas). Small woodcut portraits of the author on the main title and the text.

Botero’s “Universal Relation” is one of the earliest systematic global surveys of the world’s lands, peoples, and religions. “This vast compendium of contemporary knowledge of the known world- geographical, anthropological, economic, political, and religious - marked a new genre, namely that of political geography. The book would remain for nearly a century ‘the true and proper geopolitical manual of the whole European governing class’”. (Headley 1134)

This is the first edition of this book to include the second part of Part IV, which is illustrated with 32 woodcuts of great ethnographic and artistic interest. “Now attributed to the Renaissance genius Hans Burgkmair, the 30 full-page and 2 half-page woodcuts fall into two sections: the first group depict semi-human monsters and the remainder represent natives of India, Guinea, and East Africa. Walter Oakeshott’s 1960 study claims this was “the first serious study of native life and dress made for publication in a European travel book.’” (Princeton Graphic Arts Collection)

These extraordinary images depict Indigenous peoples and fantastical creatures from the Africa, Asia and Europe. The images are paired with explanatory ethnographic notes. The text that accompanies the woodcuts often includes ethnographic details about the Indigenous peoples’ appearance (hair, nails, etc.), clothing, jewelry, funerary rites, childrearing, occupations, and government.

Especially vivid are the scenes from the Indian kingdom of Cochin (see below for additional details). Woodcuts depict the King being borne on a platform, warriors carrying weapons, and several showing musicians playing their instruments. Mythical creatures portrayed include an African man with a monstrously long neck, a Libyan woman whose breasts hang down to her knees, and an Arabian man with three eyes upon the forehead and two hands on each arm.

The author, the former Jesuit (he was expelled from the Order) Giovanni Botero organizes his geographical survey into four sections: the Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe, each of which is illustrated by a folding map. He describes the nations of the world, their religions and beliefs, and the difficulty of converting certain peoples to Christianity. His style is readable and conversational, rather than dryly analytical. In describing Florida, he writes, "Florida is a province 400 miles long, . . . the land is pleasant and productive of every fruit. The Spaniards have attempted it several times unsuccessfully, because of the reports they had of its gold, silver, jewels, and pearls. The inhabitants go almost naked, except that the richer ones wear some skins of marten or sable. They live by hunting. They have a kind of deer, from which they draw the same benefits of milk and dairy products that we obtain from cows.”

Botero drew on missionary and traveler reports, and he advanced the idea that empire and evangelization were mutually reinforcing: political stability and commerce prepared the ground for Christian conversion. Botero judged civilizations according to their literacy and government, praising empires such as China and the Inca as more civilized, viewing them as providentially ready for the Gospel, and portrayed nomadic societies as least developed.

An excellent example of the richness and variety of the text and illustrations is the section on the Indian Kingdom of Cochin and its people.

In one image, the King is shown being carried about on a raised platform by four youths, covered only from the loins downward with a most splendid cloth of silk and gold that hangs about his sides. Around his waist he wears a broad girdle richly adorned and set with pearls and gems of inestimable value. His hair falls loose upon his neck, and upon his head he wears a long lock; from his ears hang five golden rings, each suspended from the next; and in his hand he holds a scepter turned toward the people. And instead of a parasol, there is borne above his head, on the top of a staff, a circle skillfully woven and interlaced with palm leaves.

The people of Conchin are described at length: they ordinarily devote themselves to soldiery, to which they apply from their earliest age, beginning from seven years upward, going to the school of the military art. Botero informs us that “These peoples are agile, and to exercise all the parts of the body they anoint themselves with certain oils that so loosen the joints that they seem to have no bones. They always fight naked, having only the part of the privates covered below the navel, both in front and behind. Their arms are the sword and target, and they always fight on foot, whence their armies consist only of infantry, or else naval forces. Their swords are in the fashion of a greatsword, yet they wield it with a single hand, being very dexterous, fierce, and of large stature. At the tip, instead of a point, the sword ends in a kind of rounded knob. In this manner they follow the King, both to render him courtly attendance and for his defense.”

“They also practice archery; therefore they always go armed with a quiver full of arrows, bound at the back of the flank, and carry a small lance—or rather, a dart—in the right hand, and the bow in the left, resting upon the shoulder. So skilled are they, and so swiftly and surely do they shoot, that it is said they can split a single hair in the middle even from afar. On the left side, walks a man bearing a long and immense halberd, with a turban upon his head of very fine linen, who, as he walks, keeps his gaze ever fixed upon his lord.

Another woodcut shows three people, one playing a drum, one a flute, and the third holding a spear:

“This is one who plays the drum in the same company before the platform or dais on which they bear the King. The drum is not very large but of moderate size, entirely bound with rings of metal, and at the other end fitted with small bells, so that, as he strikes the drum with the little mallet, both drum and bells sound together in harmony. Following in order behind are four wind instruments, and in his company. These musicians go two by two in front: the first plays a horn, and the other a long, extended trumpet with a banner of silk fastened to it, all adorned and bordered with small bells that produce harmony as the wind stirs the said banner.”

The woodcuts depict a number of men, women, and children in various states of dress, adorned with a variety of jewelry, including necklaces and bracelets: “These people go naked except below the navel, where they gird themselves with a most beautiful cloth of silk and of the finest linen. They wear their hair plaited like women’s, some loose and some tied at the crown of the head with a band, the rest flowing down toward the neck. In their ears they wear earrings of double rings, one hanging within the other. And they are Moors.”

Three woodcuts depict Indian children with adults, and Botero provides a detailed description of child rearing customs and practices: “The custom is that women amuse themselves with their children, sitting withdrawn upon some hillside or along the bank of a harbor, passing the time with their little ones. The women go naked, having only a cloth about the loins that covers the shameful parts, and the young maidens in particular do not hold back through excessive modesty. They carry a long palm branch in their hands. They wear no ornament upon the head; they let their hair fall down, which is extraordinarily thick and long, so that it sometimes covers the whole body down to the knees. They nurse and caress their children with loving fondness, as we also do among ourselves, giving them some apple or other fruit so that the child may stretch out its hand and make caresses.”

Further reading: Headley, "Geography and Empire in the Late Renaissance: Botero's Assignment, Western Universalism, and the Civilizing Process", in: Renaissance Quarterly 53 (2000), pp. 1119-1155.

Botero’s “Universal Relation” is one of the earliest systematic global surveys of the world’s lands, peoples, and religions. “This vast compendium of contemporary knowledge of the known world- geographical, anthropological, economic, political, and religious - marked a new genre, namely that of political geography. The book would remain for nearly a century ‘the true and proper geopolitical manual of the whole European governing class’”. (Headley 1134)

This is the first edition of this book to include the second part of Part IV, which is illustrated with 32 woodcuts of great ethnographic and artistic interest. “Now attributed to the Renaissance genius Hans Burgkmair, the 30 full-page and 2 half-page woodcuts fall into two sections: the first group depict semi-human monsters and the remainder represent natives of India, Guinea, and East Africa. Walter Oakeshott’s 1960 study claims this was “the first serious study of native life and dress made for publication in a European travel book.’” (Princeton Graphic Arts Collection)

These extraordinary images depict Indigenous peoples and fantastical creatures from the Africa, Asia and Europe. The images are paired with explanatory ethnographic notes. The text that accompanies the woodcuts often includes ethnographic details about the Indigenous peoples’ appearance (hair, nails, etc.), clothing, jewelry, funerary rites, childrearing, occupations, and government.

Especially vivid are the scenes from the Indian kingdom of Cochin (see below for additional details). Woodcuts depict the King being borne on a platform, warriors carrying weapons, and several showing musicians playing their instruments. Mythical creatures portrayed include an African man with a monstrously long neck, a Libyan woman whose breasts hang down to her knees, and an Arabian man with three eyes upon the forehead and two hands on each arm.

The author, the former Jesuit (he was expelled from the Order) Giovanni Botero organizes his geographical survey into four sections: the Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe, each of which is illustrated by a folding map. He describes the nations of the world, their religions and beliefs, and the difficulty of converting certain peoples to Christianity. His style is readable and conversational, rather than dryly analytical. In describing Florida, he writes, "Florida is a province 400 miles long, . . . the land is pleasant and productive of every fruit. The Spaniards have attempted it several times unsuccessfully, because of the reports they had of its gold, silver, jewels, and pearls. The inhabitants go almost naked, except that the richer ones wear some skins of marten or sable. They live by hunting. They have a kind of deer, from which they draw the same benefits of milk and dairy products that we obtain from cows.”

Botero drew on missionary and traveler reports, and he advanced the idea that empire and evangelization were mutually reinforcing: political stability and commerce prepared the ground for Christian conversion. Botero judged civilizations according to their literacy and government, praising empires such as China and the Inca as more civilized, viewing them as providentially ready for the Gospel, and portrayed nomadic societies as least developed.

An excellent example of the richness and variety of the text and illustrations is the section on the Indian Kingdom of Cochin and its people.

In one image, the King is shown being carried about on a raised platform by four youths, covered only from the loins downward with a most splendid cloth of silk and gold that hangs about his sides. Around his waist he wears a broad girdle richly adorned and set with pearls and gems of inestimable value. His hair falls loose upon his neck, and upon his head he wears a long lock; from his ears hang five golden rings, each suspended from the next; and in his hand he holds a scepter turned toward the people. And instead of a parasol, there is borne above his head, on the top of a staff, a circle skillfully woven and interlaced with palm leaves.

The people of Conchin are described at length: they ordinarily devote themselves to soldiery, to which they apply from their earliest age, beginning from seven years upward, going to the school of the military art. Botero informs us that “These peoples are agile, and to exercise all the parts of the body they anoint themselves with certain oils that so loosen the joints that they seem to have no bones. They always fight naked, having only the part of the privates covered below the navel, both in front and behind. Their arms are the sword and target, and they always fight on foot, whence their armies consist only of infantry, or else naval forces. Their swords are in the fashion of a greatsword, yet they wield it with a single hand, being very dexterous, fierce, and of large stature. At the tip, instead of a point, the sword ends in a kind of rounded knob. In this manner they follow the King, both to render him courtly attendance and for his defense.”

“They also practice archery; therefore they always go armed with a quiver full of arrows, bound at the back of the flank, and carry a small lance—or rather, a dart—in the right hand, and the bow in the left, resting upon the shoulder. So skilled are they, and so swiftly and surely do they shoot, that it is said they can split a single hair in the middle even from afar. On the left side, walks a man bearing a long and immense halberd, with a turban upon his head of very fine linen, who, as he walks, keeps his gaze ever fixed upon his lord.

Another woodcut shows three people, one playing a drum, one a flute, and the third holding a spear:

“This is one who plays the drum in the same company before the platform or dais on which they bear the King. The drum is not very large but of moderate size, entirely bound with rings of metal, and at the other end fitted with small bells, so that, as he strikes the drum with the little mallet, both drum and bells sound together in harmony. Following in order behind are four wind instruments, and in his company. These musicians go two by two in front: the first plays a horn, and the other a long, extended trumpet with a banner of silk fastened to it, all adorned and bordered with small bells that produce harmony as the wind stirs the said banner.”

The woodcuts depict a number of men, women, and children in various states of dress, adorned with a variety of jewelry, including necklaces and bracelets: “These people go naked except below the navel, where they gird themselves with a most beautiful cloth of silk and of the finest linen. They wear their hair plaited like women’s, some loose and some tied at the crown of the head with a band, the rest flowing down toward the neck. In their ears they wear earrings of double rings, one hanging within the other. And they are Moors.”

Three woodcuts depict Indian children with adults, and Botero provides a detailed description of child rearing customs and practices: “The custom is that women amuse themselves with their children, sitting withdrawn upon some hillside or along the bank of a harbor, passing the time with their little ones. The women go naked, having only a cloth about the loins that covers the shameful parts, and the young maidens in particular do not hold back through excessive modesty. They carry a long palm branch in their hands. They wear no ornament upon the head; they let their hair fall down, which is extraordinarily thick and long, so that it sometimes covers the whole body down to the knees. They nurse and caress their children with loving fondness, as we also do among ourselves, giving them some apple or other fruit so that the child may stretch out its hand and make caresses.”

Further reading: Headley, "Geography and Empire in the Late Renaissance: Botero's Assignment, Western Universalism, and the Civilizing Process", in: Renaissance Quarterly 53 (2000), pp. 1119-1155.