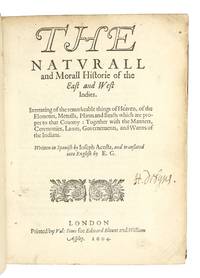

The Naturall and Morall Historie of the East and West Indies. Intreating of the remarkeable things of heaven, of the elements, mettalls, plants and beasts which are proper to that country: together with the manners, ceremonies, lawes, governements, and warres of the Indians

- SIGNED Hardcover

- London: Val: Sims for Edward Blount and William Aspley, 1604

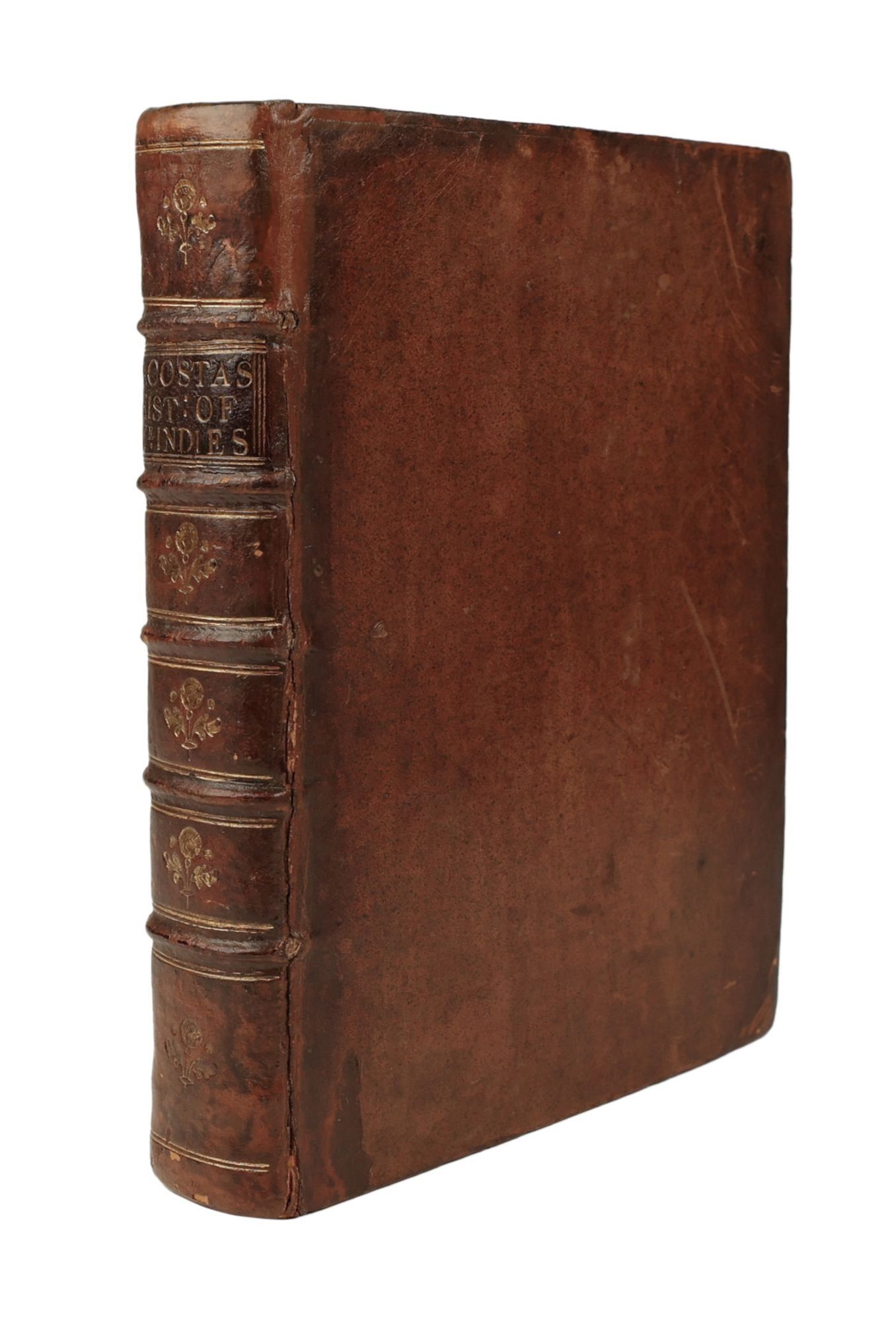

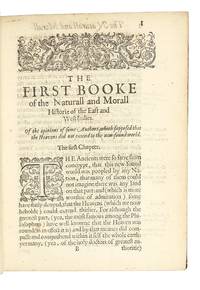

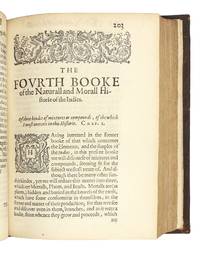

London: Val: Sims for Edward Blount and William Aspley, 1604. FIRST ENGLISH EDITION (1st published in Spanish in 1590). Hardcover. Fine. An attractive copy bound in 18th c. calfskin (hinges and head of spine skillfully repaired, corners lightly bumped, minor wear to the boards, leather along upper hinge cracked but board firmly attached.) A fine, clean copy with very minor faults (edges of title lightly soiled, a small natural paper flaw in the headline of leaf G5, very light stains to leaves R2-3 and Aa6-7, last gathering with very pale damp-stain, final leaf with small ink spot, verso of the final leaf soiled.) With ornate woodcut head-pieces and woodcut initials at the beginning of each book. First English edition of this important and early work on the cultures, flora, fauna, and geography of the New World. Acosta’s work is especially important as a source book on the Amerindians of Mexico and Peru (where Acosta spent seventeen years, from 1571-1588), and on the natural history of Mexico, Central and South America. Acosta’s book also includes a synopsis of Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca’s account of his experiences -including his enslavement by Native Americans- during Pánfilo de Narváez’ 1527-1528 disastrous expedition to Florida and the Gulf Coast.

In Books V through VII, Acosta provides in-depth descriptions of Native linguistics, religion, and history. He speculates that the first people to inhabit the Americas arrived via the Bering Strait.

"The most convincing, detailed and reliable account of the riches and new things of America. He provided great detail in his descriptions of sailing directions, mineral wealth, trading commodities, Indian history, etc. Consequently his work operated more strongly than any other in opening the eyes of the rest of Europe to the great wealth that Spain was drawing from America" (Streeter).

As a natural historian, Acosta surpassed Fernández de Oviedo. He took a philosophical approach to natural phenomena, searching for causes and effects in a spirit of critical inquiry...The subject of his moral history is pre-Columbian civilizations, particularly the Aztecs and the Incas, whose religions, customs, and governments he admiringly compares" (Delgado-Gomez).

Acosta was a keen observer of New World plants. He "mentions most of the plants used in Peru as foodstuffs or as medicinals, and even the ornamentals. He remarks that the Indians loved flowers just for their beauty" (Shaw). There is also a detailed discussion of American plants exported to the Old World, such as ginger, and a description of the use of coca in Peru. The book also includes the earliest printed description of the tomato (p. 266-267).

Like John Frampton’s translation of Nicolás Monardes’ work on New World medicinal plants, Edward Grimeston’s translation of Acosta helped stoke the flame of the nascent English objective of American colonization. It also stimulated the English imagination and deepened popular understanding of Amerindian culture and the exotic natural environment of the New World. It "made available much new information, both geographical and philosophical, to English readers [and] important and rational ideas concerning the origins of American Indians were revealed . . . His ideas [regarding the Bering Strait migration] had a profound impact on later English writers on the subject such as Strachey, Brerewood and Purchas" (Steele, p. 17). In fact “Samuel Purchas was more profoundly indebted to Acosta than any other Early English writer [and specifically referred readers to Grimeston’s translation.]”(Mancall, The Atlantic World and Virginia 1550-1624, p. 405)

“In the years after the foundation of Jamestown, Acosta’s ‘Historie’ was cited on matters on nature and custom in ways that supported Acosta’s theory of ‘progressive barbarism.’ Moreover, it was cited specifically to re-describe Algonquian peoples of the Chesapeake as belonging to the third class of ‘barbarism’ and so to justify the dispossession of the lands on which they lived.”(Ibid. p. 404).

In Books V through VII, Acosta provides in-depth descriptions of Native linguistics, religion, and history. He speculates that the first people to inhabit the Americas arrived via the Bering Strait.

"The most convincing, detailed and reliable account of the riches and new things of America. He provided great detail in his descriptions of sailing directions, mineral wealth, trading commodities, Indian history, etc. Consequently his work operated more strongly than any other in opening the eyes of the rest of Europe to the great wealth that Spain was drawing from America" (Streeter).

As a natural historian, Acosta surpassed Fernández de Oviedo. He took a philosophical approach to natural phenomena, searching for causes and effects in a spirit of critical inquiry...The subject of his moral history is pre-Columbian civilizations, particularly the Aztecs and the Incas, whose religions, customs, and governments he admiringly compares" (Delgado-Gomez).

Acosta was a keen observer of New World plants. He "mentions most of the plants used in Peru as foodstuffs or as medicinals, and even the ornamentals. He remarks that the Indians loved flowers just for their beauty" (Shaw). There is also a detailed discussion of American plants exported to the Old World, such as ginger, and a description of the use of coca in Peru. The book also includes the earliest printed description of the tomato (p. 266-267).

Like John Frampton’s translation of Nicolás Monardes’ work on New World medicinal plants, Edward Grimeston’s translation of Acosta helped stoke the flame of the nascent English objective of American colonization. It also stimulated the English imagination and deepened popular understanding of Amerindian culture and the exotic natural environment of the New World. It "made available much new information, both geographical and philosophical, to English readers [and] important and rational ideas concerning the origins of American Indians were revealed . . . His ideas [regarding the Bering Strait migration] had a profound impact on later English writers on the subject such as Strachey, Brerewood and Purchas" (Steele, p. 17). In fact “Samuel Purchas was more profoundly indebted to Acosta than any other Early English writer [and specifically referred readers to Grimeston’s translation.]”(Mancall, The Atlantic World and Virginia 1550-1624, p. 405)

“In the years after the foundation of Jamestown, Acosta’s ‘Historie’ was cited on matters on nature and custom in ways that supported Acosta’s theory of ‘progressive barbarism.’ Moreover, it was cited specifically to re-describe Algonquian peoples of the Chesapeake as belonging to the third class of ‘barbarism’ and so to justify the dispossession of the lands on which they lived.”(Ibid. p. 404).