Rhetorica Christiana Ad Concionandi, Et Orandi Vsvm Accommodata, Vtrivsq[ue] Facvltatis Exemplis Svo Loco Insertis, Qvae Qvidem, Ex Indorvm Maxime Deprompta Svnt Historiis. Vnde Praeter Doctrinam, Svm[m]a Qvoqve Delectatio Comparabitvr. Avctore R[everen]do Admodvm P.F. Didaco Valades Totivs Ordinis Fratrvm Minorvm Regvlaris Observantiae Ol[im] procvratore Generali In Romana Cvria Ano. D[omi]ni. M.D.LXXVIIII Cvm Licentia Svperiorvm

- SIGNED Hardcover

- Perugia: Apud Petrumiacobum Petrutium, 1579

Perugia: Apud Petrumiacobum Petrutium, 1579. SOLE EDITION. Hardcover. Fine. Bound in 17th c. limp vellum (some soiling and stains; lacking ties). A fine copy with only scattered instances of marginal foxing. The edges of the title are lightly soiled and an early inscription inked out at the blank foot of the leaf. Very light ink smear to bottom blank margin of plate preceding p. 101. In addition to the engraved title, the 12 added plates on 9 lvs., (which include the folding image of the city), and the folding table, the text is illustrated with 14 additional engravings, of which 5 are full page.

The “Rhetorica Christiana” was the first work of its kind printed in Europe. The primary goal of its author, Diego de Valadés was to teach missionary preachers the rhetorical skills necessary to compose and deliver sermons specifically to an Amerindian audience. But the “Rhetorica Christiana” proved to be much more complex a production, important for the author’s account of New World society and culture, his incorporation of Native American symbolism in New World pedagogy, and the use of striking engravings not merely as illustrations but as mnemonic and didactic tools. The rhetorical method that Valadés devised relied for its special efficacy on the use of such images in conjunction with sermons. They were designed to aid comprehension of the message of the sermon and, more importantly, were intended to aid in the memorization of that message.

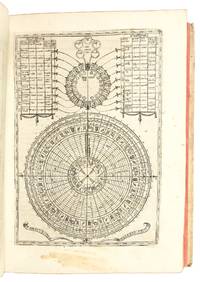

The work, with its many subsidiary objectives and it’s layering of multiple literary genres, remains unique. Valadés, who was himself an Amerindian born and raised in the New World, combined chronicle and biography with a formal art of rhetoric, incorporating into his work his experiences growing up in what is now Mexico. Furthermore, Valadés provided descriptions of Native American history, religion, and customs, as well as a history of the Franciscan missionary activities in the Americas. Thus the “Rhetorica Christiana” also provided European readers with an account of the organization of the Church in the New World and an account of the cultures that the European Christians encountered there. The written account was enlivened by the inclusion of striking engravings showing the Franciscans preaching to and educating the Native Americans, examples of the visual devices employed by the Franciscans in their preaching and teaching, and depictions of Amerindian life and cultural objects, such as an Aztec calendar wheel and – the most striking of these images - a folding depiction of a Mexica city with a stepped pyramid at its center, upon which priests perform an Aztec rite of human sacrifice (below.)

The son of a native Tlaxcalan woman and a Conquistador, Valadés was uniquely suited to write such a novel work. He was educated with other native Amerindian children by the Franciscans and later, despite his illegitimate birth and mixed parentage, was admitted to the Order. He continued his education at one of the Franciscan institutions for higher education, probably the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlaltelolco, where he clearly excelled in rhetoric. Already a native speaker of Náhuatl he tells us that he learned other indigenous languages such as Otomí and Tarasco and used his linguistic skills to proselytize among the Amerindians for twenty years. Almost all of what we know of Valadés’ life, of his experience in his native land, of his missioning, and of his ideas, comes to us from the pages of the “Rhetorica Christiana,” making it, as Don Paul Abbott observes, “as much the memoirs of a man’s life as it is a rhetorical treatise.”(Abbott, Rhetoric in the New World, p. 42)

The “Art of Memory” and Amerindian Imagery

One of the most remarkable aspects of Valadés’ book is the inclusion of 27 engravings, devised and drawn by the author himself (see the Appendix below for a descriptive list of the plates.) These images are of three types: scenes of the Franciscans preaching and educating Amerindians; examples of visual aids used to educate the Amerindians; and didactic and emblematic images to assist the reader in mastering the principles and methods expounded in the “Rhetorica Christiana.”

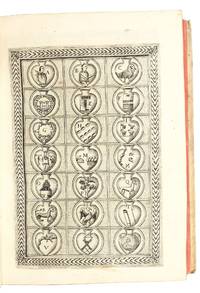

The mnemonic imagery, which in some instances incorporates native Amerindian symbolism, adds a new and important dimension to the “Art of Memory” tradition. These include elaborate images that contain visual keys to the concepts discussed in the text, as well as examples of images tailored for use in the education of the Amerindians, who, in addition to reliance on a rich oral tradition, communicated information through elaborate pictographic paintings.

“There are, says Valadés, two types of memory, natural and artificial. Natural memory is a gift of God and is not susceptible to human improvement. Artificial memory, however, which is Valadés’ concern, is available to virtually all human beings and may be improved by theory and practice. Valadés’ conception of artificial memory is almost entirely visual. It consists, he says, of places and images. Memory, then, is the creation of a ‘place’, an imaginary room, chamber, or, as Valadés suggests, temple in the mind of the speaker. This place is then filled with vivid images. The speaker then ‘travels’ through this space, encountering images, which [in the orator] prompt the appropriate portion of speech. [A tour-de-force example of this type of image is the full-page illustration showing the Franciscans’ methods for proselytizing, educating, and ministering to the Amerindians (Plate 18, p. 207).]

“Valadés contends that the natives of the New World employ a similar approach to recollection. It is the Indians’ aptitude for images that makes artificial memory function for them as surely as it did for the ancient Romans… The ability of the Indians to apprehend visual images underscores the universality of the appeal of those images. It was this visual orientation that prompted Valadés to illustrate his treatise…

“Before Valadés’ ‘Rhetorica Christiana’ illustrations had rarely, if ever, been so integral to a work on rhetoric. This is no doubt in part because of Valadés’ exceptional artistic ability. But it was also because his New World experience had convinced him that actual images must be joined with mental images for persuasion to be more effective…

“Because of the difficulties inherent in attempting to communicate across cultural barriers, Valdés extols the advantages, indeed the necessity, of augmenting verbal with visual communication. In doing so, Valadés is endorsing what was apparently a common Franciscan practice. The Franciscans resorted to the extensive use of illustrations to supplement sermonizing and to assist teaching [and] Valadés felt compelled to include several of these illustrations in the ‘Rhetorica Christiana’ as examples of the Franciscans’ pedagogical methods. The preachers made use of large, illustrated screens (‘lienzos’, literally, ‘linens’) as a backdrop to their sermons, allowing the speaker to point to the particular concept or event under discussion. One of the best-known images in the ‘Rhetorica Christiana’ portrays a preacher addressing the Indians and pointing to a series of screens depicting the Passion of Christ. Valadés reports that various aspects of Christian doctrine, including the lives of the Apostles, the Decalogue, and the seven deadly sins were demonstrated in this manner. The author also includes images that were used to graphically represent ecclesiastical and civil themes.

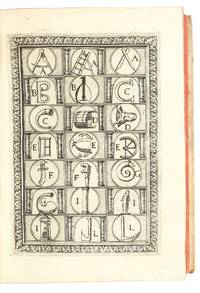

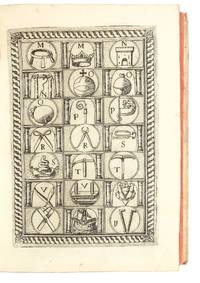

“A similar method was used to teach the Roman alphabet to the Mexica, an oral people with a pictographic writing system. [Valadés presents us with two mnemonic alphabets, the first showing correspondences between letterforms and the shapes of common objects, and the second showing the relationship between letters and sounds. In this second engraving, many of the images associated with the letters are drawn from New World culture.] By such methods Valadés and his Franciscan colleagues undertook to teach a phonetic alphabet to a people to whom such a symbol system was very foreign. For Valadés, the use of pictorial representations proved to be a ‘graceful and valuable’ way to present the word of God to an indigenous audience.” (Abbott, Rhetoric in the New World, p. 42 ff.)

Towards A New World Rhetoric

“I will say that the admirable effects of this practical application of rhetoric seems nowhere more clear than in the pacification of the natives in the New World across the ocean.”(Valadés)

The “Rhetorica Christiana” is divided into six parts. The first concerns the qualifications necessary to preach effectively: mastery of the seven liberal arts and the ability to readily apply that knowledge –from memory- in coordination with Sacred Scripture. Among the engravings in this first part, there is an image of a man, perhaps the author, composing at his desk while contemplating mnemonic devices representing oratorical principles.

The second part opens with a synoptic table outlining the components of oratory: invention, disposition, elocution, and memory. Only memory is discussed in detail and it is in this chapter that Valadés first addresses “artificial memory”, the use of visual images as mnemonic keys to concepts and ideas in order to aid memorization and to expedite recall of that information. The chapter includes an engraving of a profile head with labels for the senses (olfactory, taste, auditory, visual) and, in the area of the brain, further labels indicating the seats of imagination, fantasy, and cognition.

In the third part, concerned primarily an explication of Scripture for the aid of orators, attention is also given to ‘pronuntatio’, the use of clarity, inflection, and vocal tone to enliven sermons and make them more compelling. Such considerations are necessary to move the emotions of one’s Amerindian audience.

In the fourth part Valadés explains the three types of oratory: deliberative, demonstrative, judicial; and encourages preachers to use descriptions of New World culture and environment in their sermons so that the Amerindian audience will grasp the concepts that the preacher wishes to impart. To this end he included a short history and description of what was to become Mexico, not unlike that of the Franciscan missionaries Toribio de Benavente Motolinia (d. 1568), a contemporary of Cortes and Las Casas. The fifth part concerns the divisions of discourse, and the sixth, rhetorical figures and devices.

Leaving the New World for the Old World:

Valadés was ordained in 1555. However, he had begun his missionary activities much earlier, touring the northern territories of New Spain, specifically, Querétaro, Zacatecas, and Durango. From 1562 to 1569 he taught in the Franciscan colleges of Mexico, was made guardian of the convent at Tlaxcala, and in the same year became priest of the convent of Tepeji del Río.

In 1571, Valadés was invited to Europe to be interviewed by the general of the order, Cristóbal Cheffontaine. In 1575, he was named procurator general of the Franciscan Order at Rome, a position that allowed him to support the missions in New Spain. In 1578 he was in Padua, overseeing the publication of his “Rhetorica Christiana.”… He passed his last years at Rome, in the convent of San Pietro in Montorio. He is believed to have died around 1582.

For further reading, see Linda Báez Rubí’s excellent study: “Mnemosine Novohispánica: retórica e imágenes en el siglo XVI”, Ch. 3. and Francisco de la Maza, "Fray Diego Valades, escritor y grabador franciscano del siglo XVI, Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Esteticas, 3, p. 15-44

A Descriptive List of the Engravings:

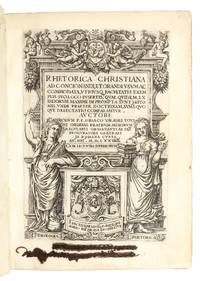

[1] Title page incorporating female allegories of Theology and Rhetoric, with the device of the Franciscans at the head, and the arms of Gregory XIII (to whom the work is dedicated) at the foot of the title.

[2] Philosopher with globe and instruments, moon, stars, sun, and other elements of allegorical significance. This engraving illustrates Valadés' commitment to the importance and necessity of universal education. (Half-page text illustration, p. 5.)

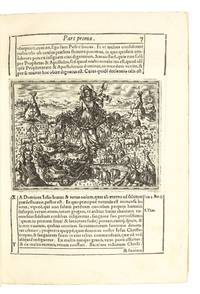

[3] Christ pouring out the River of Life from the wound in his side. Numerous allegorical, mnemonic symbols. (Half-page text illustration, p. 7.)

[4] An angel assists a writer (perhaps Valdés himself) surrounded by mnemonic imagery with his writing. Beneath the writer’s feet is the world, symbolizing his triumph over worldly desires and his dedication to God alone. (Half-page text illustration, p. 10.)

[5] Sacra Theologia. Allegorical representation of sacred theology showing a monk, standing upon books symbolizing the firm foundation of his education (grammar, logic, etc.). He points aloft to the heavenly host while preaching. (Half-page text illustration, p. 14.)

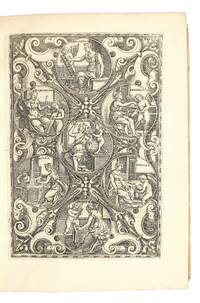

[6] Full-page emblematic engraving, with elaborate strap work and roundels showing the seven liberal arts: Arithmetic, Geometry, Astrology, Dialectics, Music, Rhetoric, and Grammar. (Full-page text illustration, p. 17.)

[7] An ancient Jewish orator delivers a sermon in front of a small temple. (Half-page text illustration, p. 25)

[8] Profile head in a decorative frame with labels for the senses (olfactory, taste, auditory, visual) and, in the area of the brain, further labels indicating the seats of imagination, fantasy, and cognition. Signed at top: "F. D. Valadés Inventor." (Half-page text illustration, p. 88.)

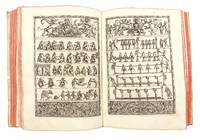

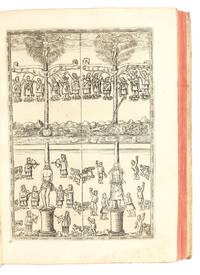

[9 & 10] Two mnemonic alphabets (in 3 plates), the first showing correspondences between letterforms and the shapes of common objects, and the second showing the relationship between letters and sounds. Many of the objects, symbols, and figures associated with the letters are drawn from New World culture, such as Huitzilopochtli with his serpent (here a caduceus) and shield. (2 full-page plates, following p. 100)

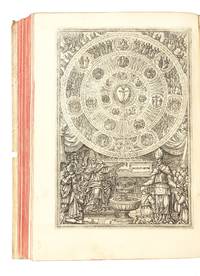

[12] Aztec calendar wheel, superimposed with figures of the European zodiac and showing the correlation of the 18 Aztec months with the Julian calendar. Signed by author in lower part of plate. (Plate preceding p. 101.)

[13] Striking bird’s-eye view of a Mexica city, presenting a synopsis of scenes observed by the first twelve Franciscans who arrived in Mexico after the Conquest, one of the most important cross-cultural encounters in the New World. The dynamic scene is dominated by an Aztec human sacrifice taking place atop a stepped pyramid within a religious enclosure. The temple is surrounded by abundant details of daily life and the natural world, including: dancers; games; music; food preparation; women carrying large jugs; people fishing and boating on a lake in canoes and on rafts; a burial ceremony; sun and moon worship; agricultural activities, and native plants (agave, corn, the cocoa tree, pineapple, nopal, nuts, the Dragon’s Blood tree, etc.); and an array of native architecture. (Folded plate, between pp. 168 and 169. Signed by author in lower image.)

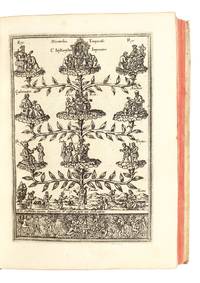

[14] Secular hierarchy on the branches of a highly stylized tree, with the emperor residing at the top, descending down to Hell at the bottom, as a reminder to the disobedient not to resist the authority of the emperor. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

[15] Mnemonic emblem in the form of a large cross representing the human body to the waist (head, left arm, right arm, navel) flanked by a ship with the crucifix as its mast and, at right, a tempietto. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

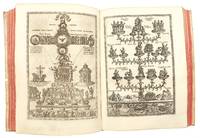

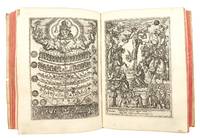

[16] Stylized depiction of the hierarchical structure of the Church, with the Pope at the top and Native Americans receiving baptism at the bottom. Beneath the ground, sinners (presumably “pagans”) are roasted and tortured by devils in the flames of Hell –a sobering encouragement to those who resist conversion. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

[17] An elaborate scene showing the bleeding heart of the crucified Christ filling the Treasury of Merit. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

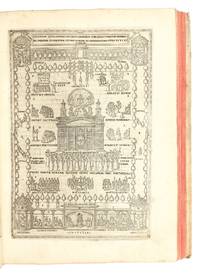

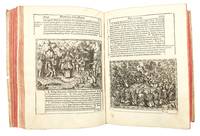

[18] An important full-page illustration of the Franciscan method of evangelization as carried out by the Order in the New World. Within a stylized, rectangular compound (an example of a “memory palace”), the Franciscans are shown preaching to, educating, and ministering to groups of Amerindians who are separated by age and gender: girls, boys, men, women. Within the colonnade that fronts the architectural complex the following scenes are clearly labeled: confession, communion, mass, performance of last rites, and the administration of justice. Within the central courtyard Franciscan brothers are shown teaching penitence, Church doctrine, and the sacraments of marriage and confession. Within this same courtyard there are scenes of marriage, baptism, and a funeral. In two scenes Franciscans are shown teaching their Mexica students using lienzos. The first shows the Creation of the world while the second shows symbolic pictures of the kind described and illustrated in the text. The Franciscan in the second scene is identified as Valadés’ contemporary and co-missioner, the Belgian Pedro de Gante (1480-1572), one of the original twelve Franciscans to arrive in Mexico and who composed a work on Christian doctrine in Nahuatl. At the center of the entire scene is a procession of the first Franciscan New World martyrs who bear upon their shoulders a church. They are led by Saint Francis himself and the last in the line is identified as Martín de Valencia (1474-1534), who led the first Franciscan mission to Mexico, in 1534. (Full-page text illustration, Signed by author above lower register of images. p. [207])

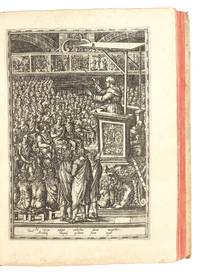

[19] One of the best-known images in the ‘Rhetorica Christiana’, this scene portrays the interior of a church, with a friar in a pulpit preaching to his Amerindian congregation. The preacher points to a series of lienzos, painted linen panels, adapted from those used by the Amerindians, depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ “so that later they (the congregation) may better retain those things (the content of the sermon).” In the first row sit the Amerindian magistrates and governors. For the rest, Valadés notes that women and men comingle equally in the crowd, crouching on their heels, in no established order. This image was later adapted for use as the frontispiece of Torquemada's 1615 “Monarchia Indiana.” (Full-page text illustration, p. [211])

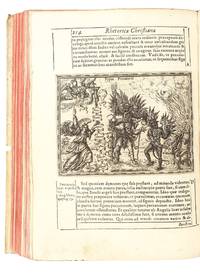

[20] “Typus Peccatoris.” A grotesque image of a sinner beset by winged devils that tempt him toward a throne of flames while, at left, an angel urges him to seek the glories of heaven. (Half-page text illustration, p. 214)

[21] This image relates to the holiness of matrimony and the punishment for infidelity, which leads to hell. At top, Native Americans wearing tilmas are suspended from two trees while a devil tries to pull one down with a chain. Below the male adulterer is tied to a pole as spears and arrows strike his body. The adulteress is stoned to death according to Nahua custom. (On recto of leaf following p. 212)

[22] “The Great Chain of Being”, the linkage between all stages of the universe with God as its creator, redeemer, and remunerator, at the top seated by His Son. The various rows represent paradise (nature, animals, water, and earth in harmony), humans, and angels. Below is the fall of the rebel angels. Among the images of animals is a unicorn. (Signed by author at lower middle. Verso of leaf following p. 212)

[23] A sumptuous image that effectively demonstrates the psychological power of the lienzo when used in conjunction with preaching. A Franciscan friar and his Amerindian congregation stand at the foot of an elaborate scene of Christ's crucifixion. The preacher uses a pointer to explain elements of the scene. The image is unique in that the friar and his audience actually seem to inhabit the scene, in the manner of donor figures in traditional European painting. (Signed by author at lower left. Recto of leaf preceding p. 213.)

[24 & 25] Stages of temptation, sin, and punishment, showing, on the left-hand page, sinners afflicted by sinful thoughts and deeds (with snakes, insects, scorpions, and toads falling from their mouths, and comingling with dragons hydras, and wild dogs.) The right-hand page shows those same souls enslaved by devils, chained to pillars, and being marched away wearing wooden yokes. At the head and foot of both engravings are elaborate, ghastly images of Satan and Hell. (Two full-page text illustrations, pp. [216 & 217])

[26] In a mountainous landscape with a fire pit in the foreground, a missionary and his party carrying religious artifacts meet a small group of Native Americans with bows, arrows, and shields. A child and two women kneel before the missionary. (Signed by author in lower part of image at center. Half-page text illustration on p. 224.)

[27] Native Americans with bows, quivers, and arrows sit in a circle around a missionary in a wooded landscape with a village in distance. (Half-page text illustration, p. 225).

The “Rhetorica Christiana” was the first work of its kind printed in Europe. The primary goal of its author, Diego de Valadés was to teach missionary preachers the rhetorical skills necessary to compose and deliver sermons specifically to an Amerindian audience. But the “Rhetorica Christiana” proved to be much more complex a production, important for the author’s account of New World society and culture, his incorporation of Native American symbolism in New World pedagogy, and the use of striking engravings not merely as illustrations but as mnemonic and didactic tools. The rhetorical method that Valadés devised relied for its special efficacy on the use of such images in conjunction with sermons. They were designed to aid comprehension of the message of the sermon and, more importantly, were intended to aid in the memorization of that message.

The work, with its many subsidiary objectives and it’s layering of multiple literary genres, remains unique. Valadés, who was himself an Amerindian born and raised in the New World, combined chronicle and biography with a formal art of rhetoric, incorporating into his work his experiences growing up in what is now Mexico. Furthermore, Valadés provided descriptions of Native American history, religion, and customs, as well as a history of the Franciscan missionary activities in the Americas. Thus the “Rhetorica Christiana” also provided European readers with an account of the organization of the Church in the New World and an account of the cultures that the European Christians encountered there. The written account was enlivened by the inclusion of striking engravings showing the Franciscans preaching to and educating the Native Americans, examples of the visual devices employed by the Franciscans in their preaching and teaching, and depictions of Amerindian life and cultural objects, such as an Aztec calendar wheel and – the most striking of these images - a folding depiction of a Mexica city with a stepped pyramid at its center, upon which priests perform an Aztec rite of human sacrifice (below.)

The son of a native Tlaxcalan woman and a Conquistador, Valadés was uniquely suited to write such a novel work. He was educated with other native Amerindian children by the Franciscans and later, despite his illegitimate birth and mixed parentage, was admitted to the Order. He continued his education at one of the Franciscan institutions for higher education, probably the Colegio de Santa Cruz de Tlaltelolco, where he clearly excelled in rhetoric. Already a native speaker of Náhuatl he tells us that he learned other indigenous languages such as Otomí and Tarasco and used his linguistic skills to proselytize among the Amerindians for twenty years. Almost all of what we know of Valadés’ life, of his experience in his native land, of his missioning, and of his ideas, comes to us from the pages of the “Rhetorica Christiana,” making it, as Don Paul Abbott observes, “as much the memoirs of a man’s life as it is a rhetorical treatise.”(Abbott, Rhetoric in the New World, p. 42)

The “Art of Memory” and Amerindian Imagery

One of the most remarkable aspects of Valadés’ book is the inclusion of 27 engravings, devised and drawn by the author himself (see the Appendix below for a descriptive list of the plates.) These images are of three types: scenes of the Franciscans preaching and educating Amerindians; examples of visual aids used to educate the Amerindians; and didactic and emblematic images to assist the reader in mastering the principles and methods expounded in the “Rhetorica Christiana.”

The mnemonic imagery, which in some instances incorporates native Amerindian symbolism, adds a new and important dimension to the “Art of Memory” tradition. These include elaborate images that contain visual keys to the concepts discussed in the text, as well as examples of images tailored for use in the education of the Amerindians, who, in addition to reliance on a rich oral tradition, communicated information through elaborate pictographic paintings.

“There are, says Valadés, two types of memory, natural and artificial. Natural memory is a gift of God and is not susceptible to human improvement. Artificial memory, however, which is Valadés’ concern, is available to virtually all human beings and may be improved by theory and practice. Valadés’ conception of artificial memory is almost entirely visual. It consists, he says, of places and images. Memory, then, is the creation of a ‘place’, an imaginary room, chamber, or, as Valadés suggests, temple in the mind of the speaker. This place is then filled with vivid images. The speaker then ‘travels’ through this space, encountering images, which [in the orator] prompt the appropriate portion of speech. [A tour-de-force example of this type of image is the full-page illustration showing the Franciscans’ methods for proselytizing, educating, and ministering to the Amerindians (Plate 18, p. 207).]

“Valadés contends that the natives of the New World employ a similar approach to recollection. It is the Indians’ aptitude for images that makes artificial memory function for them as surely as it did for the ancient Romans… The ability of the Indians to apprehend visual images underscores the universality of the appeal of those images. It was this visual orientation that prompted Valadés to illustrate his treatise…

“Before Valadés’ ‘Rhetorica Christiana’ illustrations had rarely, if ever, been so integral to a work on rhetoric. This is no doubt in part because of Valadés’ exceptional artistic ability. But it was also because his New World experience had convinced him that actual images must be joined with mental images for persuasion to be more effective…

“Because of the difficulties inherent in attempting to communicate across cultural barriers, Valdés extols the advantages, indeed the necessity, of augmenting verbal with visual communication. In doing so, Valadés is endorsing what was apparently a common Franciscan practice. The Franciscans resorted to the extensive use of illustrations to supplement sermonizing and to assist teaching [and] Valadés felt compelled to include several of these illustrations in the ‘Rhetorica Christiana’ as examples of the Franciscans’ pedagogical methods. The preachers made use of large, illustrated screens (‘lienzos’, literally, ‘linens’) as a backdrop to their sermons, allowing the speaker to point to the particular concept or event under discussion. One of the best-known images in the ‘Rhetorica Christiana’ portrays a preacher addressing the Indians and pointing to a series of screens depicting the Passion of Christ. Valadés reports that various aspects of Christian doctrine, including the lives of the Apostles, the Decalogue, and the seven deadly sins were demonstrated in this manner. The author also includes images that were used to graphically represent ecclesiastical and civil themes.

“A similar method was used to teach the Roman alphabet to the Mexica, an oral people with a pictographic writing system. [Valadés presents us with two mnemonic alphabets, the first showing correspondences between letterforms and the shapes of common objects, and the second showing the relationship between letters and sounds. In this second engraving, many of the images associated with the letters are drawn from New World culture.] By such methods Valadés and his Franciscan colleagues undertook to teach a phonetic alphabet to a people to whom such a symbol system was very foreign. For Valadés, the use of pictorial representations proved to be a ‘graceful and valuable’ way to present the word of God to an indigenous audience.” (Abbott, Rhetoric in the New World, p. 42 ff.)

Towards A New World Rhetoric

“I will say that the admirable effects of this practical application of rhetoric seems nowhere more clear than in the pacification of the natives in the New World across the ocean.”(Valadés)

The “Rhetorica Christiana” is divided into six parts. The first concerns the qualifications necessary to preach effectively: mastery of the seven liberal arts and the ability to readily apply that knowledge –from memory- in coordination with Sacred Scripture. Among the engravings in this first part, there is an image of a man, perhaps the author, composing at his desk while contemplating mnemonic devices representing oratorical principles.

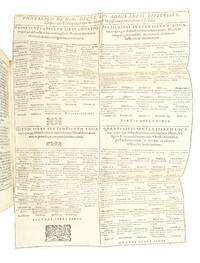

The second part opens with a synoptic table outlining the components of oratory: invention, disposition, elocution, and memory. Only memory is discussed in detail and it is in this chapter that Valadés first addresses “artificial memory”, the use of visual images as mnemonic keys to concepts and ideas in order to aid memorization and to expedite recall of that information. The chapter includes an engraving of a profile head with labels for the senses (olfactory, taste, auditory, visual) and, in the area of the brain, further labels indicating the seats of imagination, fantasy, and cognition.

In the third part, concerned primarily an explication of Scripture for the aid of orators, attention is also given to ‘pronuntatio’, the use of clarity, inflection, and vocal tone to enliven sermons and make them more compelling. Such considerations are necessary to move the emotions of one’s Amerindian audience.

In the fourth part Valadés explains the three types of oratory: deliberative, demonstrative, judicial; and encourages preachers to use descriptions of New World culture and environment in their sermons so that the Amerindian audience will grasp the concepts that the preacher wishes to impart. To this end he included a short history and description of what was to become Mexico, not unlike that of the Franciscan missionaries Toribio de Benavente Motolinia (d. 1568), a contemporary of Cortes and Las Casas. The fifth part concerns the divisions of discourse, and the sixth, rhetorical figures and devices.

Leaving the New World for the Old World:

Valadés was ordained in 1555. However, he had begun his missionary activities much earlier, touring the northern territories of New Spain, specifically, Querétaro, Zacatecas, and Durango. From 1562 to 1569 he taught in the Franciscan colleges of Mexico, was made guardian of the convent at Tlaxcala, and in the same year became priest of the convent of Tepeji del Río.

In 1571, Valadés was invited to Europe to be interviewed by the general of the order, Cristóbal Cheffontaine. In 1575, he was named procurator general of the Franciscan Order at Rome, a position that allowed him to support the missions in New Spain. In 1578 he was in Padua, overseeing the publication of his “Rhetorica Christiana.”… He passed his last years at Rome, in the convent of San Pietro in Montorio. He is believed to have died around 1582.

For further reading, see Linda Báez Rubí’s excellent study: “Mnemosine Novohispánica: retórica e imágenes en el siglo XVI”, Ch. 3. and Francisco de la Maza, "Fray Diego Valades, escritor y grabador franciscano del siglo XVI, Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Esteticas, 3, p. 15-44

A Descriptive List of the Engravings:

[1] Title page incorporating female allegories of Theology and Rhetoric, with the device of the Franciscans at the head, and the arms of Gregory XIII (to whom the work is dedicated) at the foot of the title.

[2] Philosopher with globe and instruments, moon, stars, sun, and other elements of allegorical significance. This engraving illustrates Valadés' commitment to the importance and necessity of universal education. (Half-page text illustration, p. 5.)

[3] Christ pouring out the River of Life from the wound in his side. Numerous allegorical, mnemonic symbols. (Half-page text illustration, p. 7.)

[4] An angel assists a writer (perhaps Valdés himself) surrounded by mnemonic imagery with his writing. Beneath the writer’s feet is the world, symbolizing his triumph over worldly desires and his dedication to God alone. (Half-page text illustration, p. 10.)

[5] Sacra Theologia. Allegorical representation of sacred theology showing a monk, standing upon books symbolizing the firm foundation of his education (grammar, logic, etc.). He points aloft to the heavenly host while preaching. (Half-page text illustration, p. 14.)

[6] Full-page emblematic engraving, with elaborate strap work and roundels showing the seven liberal arts: Arithmetic, Geometry, Astrology, Dialectics, Music, Rhetoric, and Grammar. (Full-page text illustration, p. 17.)

[7] An ancient Jewish orator delivers a sermon in front of a small temple. (Half-page text illustration, p. 25)

[8] Profile head in a decorative frame with labels for the senses (olfactory, taste, auditory, visual) and, in the area of the brain, further labels indicating the seats of imagination, fantasy, and cognition. Signed at top: "F. D. Valadés Inventor." (Half-page text illustration, p. 88.)

[9 & 10] Two mnemonic alphabets (in 3 plates), the first showing correspondences between letterforms and the shapes of common objects, and the second showing the relationship between letters and sounds. Many of the objects, symbols, and figures associated with the letters are drawn from New World culture, such as Huitzilopochtli with his serpent (here a caduceus) and shield. (2 full-page plates, following p. 100)

[12] Aztec calendar wheel, superimposed with figures of the European zodiac and showing the correlation of the 18 Aztec months with the Julian calendar. Signed by author in lower part of plate. (Plate preceding p. 101.)

[13] Striking bird’s-eye view of a Mexica city, presenting a synopsis of scenes observed by the first twelve Franciscans who arrived in Mexico after the Conquest, one of the most important cross-cultural encounters in the New World. The dynamic scene is dominated by an Aztec human sacrifice taking place atop a stepped pyramid within a religious enclosure. The temple is surrounded by abundant details of daily life and the natural world, including: dancers; games; music; food preparation; women carrying large jugs; people fishing and boating on a lake in canoes and on rafts; a burial ceremony; sun and moon worship; agricultural activities, and native plants (agave, corn, the cocoa tree, pineapple, nopal, nuts, the Dragon’s Blood tree, etc.); and an array of native architecture. (Folded plate, between pp. 168 and 169. Signed by author in lower image.)

[14] Secular hierarchy on the branches of a highly stylized tree, with the emperor residing at the top, descending down to Hell at the bottom, as a reminder to the disobedient not to resist the authority of the emperor. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

[15] Mnemonic emblem in the form of a large cross representing the human body to the waist (head, left arm, right arm, navel) flanked by a ship with the crucifix as its mast and, at right, a tempietto. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

[16] Stylized depiction of the hierarchical structure of the Church, with the Pope at the top and Native Americans receiving baptism at the bottom. Beneath the ground, sinners (presumably “pagans”) are roasted and tortured by devils in the flames of Hell –a sobering encouragement to those who resist conversion. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

[17] An elaborate scene showing the bleeding heart of the crucified Christ filling the Treasury of Merit. (on a two-sided plate bound between p. 180 and 181.)

[18] An important full-page illustration of the Franciscan method of evangelization as carried out by the Order in the New World. Within a stylized, rectangular compound (an example of a “memory palace”), the Franciscans are shown preaching to, educating, and ministering to groups of Amerindians who are separated by age and gender: girls, boys, men, women. Within the colonnade that fronts the architectural complex the following scenes are clearly labeled: confession, communion, mass, performance of last rites, and the administration of justice. Within the central courtyard Franciscan brothers are shown teaching penitence, Church doctrine, and the sacraments of marriage and confession. Within this same courtyard there are scenes of marriage, baptism, and a funeral. In two scenes Franciscans are shown teaching their Mexica students using lienzos. The first shows the Creation of the world while the second shows symbolic pictures of the kind described and illustrated in the text. The Franciscan in the second scene is identified as Valadés’ contemporary and co-missioner, the Belgian Pedro de Gante (1480-1572), one of the original twelve Franciscans to arrive in Mexico and who composed a work on Christian doctrine in Nahuatl. At the center of the entire scene is a procession of the first Franciscan New World martyrs who bear upon their shoulders a church. They are led by Saint Francis himself and the last in the line is identified as Martín de Valencia (1474-1534), who led the first Franciscan mission to Mexico, in 1534. (Full-page text illustration, Signed by author above lower register of images. p. [207])

[19] One of the best-known images in the ‘Rhetorica Christiana’, this scene portrays the interior of a church, with a friar in a pulpit preaching to his Amerindian congregation. The preacher points to a series of lienzos, painted linen panels, adapted from those used by the Amerindians, depicting scenes from the Passion of Christ “so that later they (the congregation) may better retain those things (the content of the sermon).” In the first row sit the Amerindian magistrates and governors. For the rest, Valadés notes that women and men comingle equally in the crowd, crouching on their heels, in no established order. This image was later adapted for use as the frontispiece of Torquemada's 1615 “Monarchia Indiana.” (Full-page text illustration, p. [211])

[20] “Typus Peccatoris.” A grotesque image of a sinner beset by winged devils that tempt him toward a throne of flames while, at left, an angel urges him to seek the glories of heaven. (Half-page text illustration, p. 214)

[21] This image relates to the holiness of matrimony and the punishment for infidelity, which leads to hell. At top, Native Americans wearing tilmas are suspended from two trees while a devil tries to pull one down with a chain. Below the male adulterer is tied to a pole as spears and arrows strike his body. The adulteress is stoned to death according to Nahua custom. (On recto of leaf following p. 212)

[22] “The Great Chain of Being”, the linkage between all stages of the universe with God as its creator, redeemer, and remunerator, at the top seated by His Son. The various rows represent paradise (nature, animals, water, and earth in harmony), humans, and angels. Below is the fall of the rebel angels. Among the images of animals is a unicorn. (Signed by author at lower middle. Verso of leaf following p. 212)

[23] A sumptuous image that effectively demonstrates the psychological power of the lienzo when used in conjunction with preaching. A Franciscan friar and his Amerindian congregation stand at the foot of an elaborate scene of Christ's crucifixion. The preacher uses a pointer to explain elements of the scene. The image is unique in that the friar and his audience actually seem to inhabit the scene, in the manner of donor figures in traditional European painting. (Signed by author at lower left. Recto of leaf preceding p. 213.)

[24 & 25] Stages of temptation, sin, and punishment, showing, on the left-hand page, sinners afflicted by sinful thoughts and deeds (with snakes, insects, scorpions, and toads falling from their mouths, and comingling with dragons hydras, and wild dogs.) The right-hand page shows those same souls enslaved by devils, chained to pillars, and being marched away wearing wooden yokes. At the head and foot of both engravings are elaborate, ghastly images of Satan and Hell. (Two full-page text illustrations, pp. [216 & 217])

[26] In a mountainous landscape with a fire pit in the foreground, a missionary and his party carrying religious artifacts meet a small group of Native Americans with bows, arrows, and shields. A child and two women kneel before the missionary. (Signed by author in lower part of image at center. Half-page text illustration on p. 224.)

[27] Native Americans with bows, quivers, and arrows sit in a circle around a missionary in a wooded landscape with a village in distance. (Half-page text illustration, p. 225).