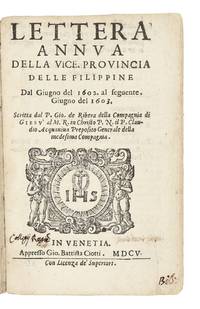

Lettera annua della Vice. Provincia delle Filippine, dal Giugno del 1602. al seguente. Giugno del 1603

- SIGNED Hardcover

- Venice: G. Battista Ciotti, 1605

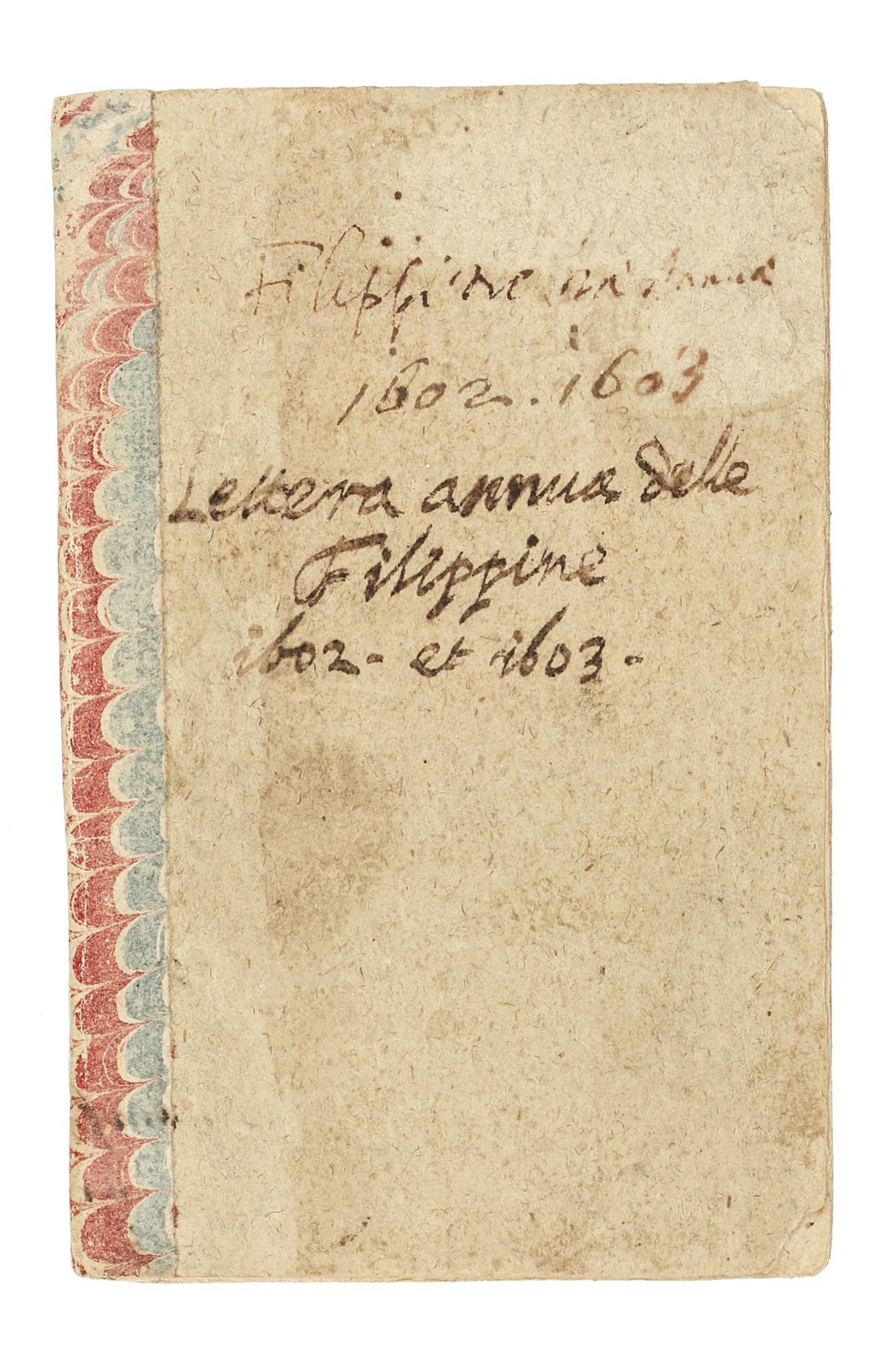

Venice: G. Battista Ciotti, 1605. SECOND EDITION (printed in the year of the first.). Hardcover. Fine. Bound in 17th c. carta rustica with a marbled guard along the spine (small losses at the corners) and the title in a 17th c. hand on the upper cover. A fine, unsophisticated copy with some very light marginal foxing, first few leaves dog-eared at lower corner, title with 17th c inscription causing small hole at corner (from ink burn.). This is only the second relation to deal exclusively with the Jesuit mission in the Philippines, preceded by Pedro Chirino's report of the previous year. It provides one of the earliest eyewitness portrayals of life among the peoples of the central Philippines. Written from Manila by Juan Ribera or Rivera, S.J. (1565-1622), the letter describes events from June 1602 to June 1603, a year marked by institutional growth and by crises of war, disease, and conversion.

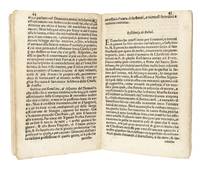

The relation provides a detailed description of the Jesuit College at Manila, where grammar, rhetoric and other courses are attended by "more than sixty students". A second college has been established at San Jose "which is carried on by means of fees which the students pay." This second college also serves as the seminary of the Society. In the course of his description of Manila, Ribera reports that the city has suffered "the greatest fire in its history" in which twenty-five people perished.

Ribera's account of Manila is followed by individual accounts of the residences at Zebu, Dulae, Carigara, Ogmuc, Bohol (and the island of Tanay), Tinagon, Cantubig, Antipolo and Silang. With the exception of Manila and Zebu, all the residences described are found "fra Indiani" ("among the natives"). In each of these residences, the Jesuits provide instruction to indigenous catechists and prepare catechumens for baptism. Almost all of the Jesuits are versed in the local languages, Tagalog and Visayan, and regular sermons are given in these languages. Ribera reports on the progress of the faith among the Filipinos (the residence at Dulac, for instance, reports 1,200 baptisms for the year) and tells of the Jesuits' efforts to root out “superstition” and combat the Devil. Ribera dedicates several pages to the fascinating story of the people of Ogmuc and their struggle against demonic possession. Later, he tells of a failed attempt by one of "the Devil's head priests" to kill all of the Jesuits at Bohol.

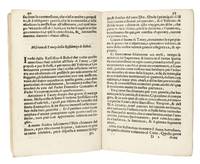

Throughout the Lettera, Ribera recounts episodes of idol destruction and exorcism in the conventional Christian language of spiritual warfare. Yet beneath these polemical terms lies a rare record of indigenous ritual and belief. He writes of a “temple of idols” (a native shrine for ancestral or nature spirits, anito or diwata) burned by missionaries, and of an “old woman who from her youth had commerce with the Demon” (a babaylan, or spirit medium) who led others to sacrifice. Elsewhere he reports that “thirty of the most obstinate, with certain witches and the most diabolical priestesses,” were baptized after renouncing “the Demon.” These accounts, though cast in the vocabulary of diabolism, preserve some of the earliest ethnographic traces of Philippine shamanic practice as seen through missionary eyes.

Illness and healing recur as intertwined themes. Ribera describes the confession and recovery of the sick at Tanay and the Isola del Fuoco (Siquijor), whose name he explains from its nightly phosphorescence. His repeated references to fever and contagion almost certainly correspond to the smallpox epidemic then devastating the Visayas between 1596 and 1603, during which, according to later Jesuit chroniclers, more than half the populations of Bohol and Leyte perished. Ribera’s accounts of possession and cure thus stand as devotional renderings of epidemic experience, interpreted through the categories of faith and sacrament.

Amid these trials, the letter also records signs of order and intellectual life. Ribera notes that the Philippine mission served as a base for Jesuit work in China, Japan, and the Moluccas, situating the islands within the Society’s global network. The present report was issued at a crucial time for the Philippine mission. The appearance of the Dutch East India Company in the Pacific caused Rome "to pay more attention to the mission in the strategic Philippines"(Lach). As the mission grew in size and numbers in the first few years of the 17th century, some of the Philippine missioners, including Ribera, sought greater autonomy from the Mexican Province. Ribera concludes his report with an appeal to Claudio Acquaviva to send more missioners to the Philippines in order to spread the Catholic faith through the Far East.

The relation provides a detailed description of the Jesuit College at Manila, where grammar, rhetoric and other courses are attended by "more than sixty students". A second college has been established at San Jose "which is carried on by means of fees which the students pay." This second college also serves as the seminary of the Society. In the course of his description of Manila, Ribera reports that the city has suffered "the greatest fire in its history" in which twenty-five people perished.

Ribera's account of Manila is followed by individual accounts of the residences at Zebu, Dulae, Carigara, Ogmuc, Bohol (and the island of Tanay), Tinagon, Cantubig, Antipolo and Silang. With the exception of Manila and Zebu, all the residences described are found "fra Indiani" ("among the natives"). In each of these residences, the Jesuits provide instruction to indigenous catechists and prepare catechumens for baptism. Almost all of the Jesuits are versed in the local languages, Tagalog and Visayan, and regular sermons are given in these languages. Ribera reports on the progress of the faith among the Filipinos (the residence at Dulac, for instance, reports 1,200 baptisms for the year) and tells of the Jesuits' efforts to root out “superstition” and combat the Devil. Ribera dedicates several pages to the fascinating story of the people of Ogmuc and their struggle against demonic possession. Later, he tells of a failed attempt by one of "the Devil's head priests" to kill all of the Jesuits at Bohol.

Throughout the Lettera, Ribera recounts episodes of idol destruction and exorcism in the conventional Christian language of spiritual warfare. Yet beneath these polemical terms lies a rare record of indigenous ritual and belief. He writes of a “temple of idols” (a native shrine for ancestral or nature spirits, anito or diwata) burned by missionaries, and of an “old woman who from her youth had commerce with the Demon” (a babaylan, or spirit medium) who led others to sacrifice. Elsewhere he reports that “thirty of the most obstinate, with certain witches and the most diabolical priestesses,” were baptized after renouncing “the Demon.” These accounts, though cast in the vocabulary of diabolism, preserve some of the earliest ethnographic traces of Philippine shamanic practice as seen through missionary eyes.

Illness and healing recur as intertwined themes. Ribera describes the confession and recovery of the sick at Tanay and the Isola del Fuoco (Siquijor), whose name he explains from its nightly phosphorescence. His repeated references to fever and contagion almost certainly correspond to the smallpox epidemic then devastating the Visayas between 1596 and 1603, during which, according to later Jesuit chroniclers, more than half the populations of Bohol and Leyte perished. Ribera’s accounts of possession and cure thus stand as devotional renderings of epidemic experience, interpreted through the categories of faith and sacrament.

Amid these trials, the letter also records signs of order and intellectual life. Ribera notes that the Philippine mission served as a base for Jesuit work in China, Japan, and the Moluccas, situating the islands within the Society’s global network. The present report was issued at a crucial time for the Philippine mission. The appearance of the Dutch East India Company in the Pacific caused Rome "to pay more attention to the mission in the strategic Philippines"(Lach). As the mission grew in size and numbers in the first few years of the 17th century, some of the Philippine missioners, including Ribera, sought greater autonomy from the Mexican Province. Ribera concludes his report with an appeal to Claudio Acquaviva to send more missioners to the Philippines in order to spread the Catholic faith through the Far East.