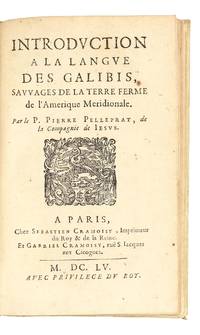

Relation des missions des PP. de la Compagnie de Iesus dans les isles, & dans la terre ferme de l’Amerique Meridionale. Divisée en deux parties. Avec une introduction à la langue des Galibis Sauvages de la terre ferme de l’Amerique

- SIGNED Hardcover

- Paris: Chez S. Cramoisy & G. Cramoisy, 1655

Paris: Chez S. Cramoisy & G. Cramoisy, 1655. SOLE EDITION. Hardcover. Fine. A very fine, unsophisticated copy in original limp vellum (with the slightest of soiling). Light toning to some gatherings (some lightly browned). Occ. spots from paper impurities. Small brown spot in blank margin of leaf F3, second count. Engraved arms of the dedicatee, Nicolas Fouquet, on the second leaf. First edition of this rare relation describing the Jesuit missions in the Caribbean and on the South American mainland, providing one of the earliest systematic accounts of the Lesser Antilles and Guiana. Much of the book is based on the author’s firsthand experiences. He describes the foundation of churches, the conversion of enslaved Africans and Indigenous nations, Indigenous culture, the moral and physical trials of evangelization, and the natural history of the islands and mainland.

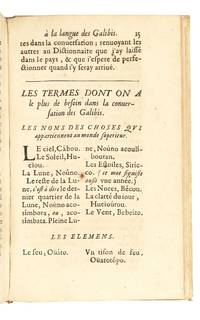

Of special importance is the third part of the work: the author’s grammar and vocabulary of the Galibi language, one of the earliest printed studies of a South American Indigenous language. Pelleprat explains the purpose of understanding Galibi: “I have composed a small grammar and vocabulary of the Galibi language, so that our Fathers who shall come after me may speak to these peoples in their own words and more easily win their souls to God.”

In 1651, Pierre Pelleprat was sent from France to the Antilles, joining Fathers Denys Mesland, François Gueymeu, and Guillaume Aubergeon. The Jesuits served the indigenous Amerindians, enslaved Africans, and Irish and French settlers. Two years later, Pelleprat and Mesland sailed for the mainland, where they established a mission on the Guarapiche River near the Gulf of Paria. After Mesland’s departure was, Pelleprat remained alone, continuing his missionary work and studying the local language. Illness forced him to return to the islands in 1654. He petitioned to return to Europe but was denied and instead lived out the remainder of his life in Mexico, dying at Puebla de los Angeles in 1667.

The preface outlines the establishment of the Jesuit mission in the French Caribbean following the founding of Martinique and Guadeloupe in 1635. Pelleprat recounts the arrival of the Jesuits and their efforts to learn the native languages in order to communicate doctrine, record confessions, and translate prayers. His descriptions of the climate, geography, and local governance of the islands are accompanied by remarks on Indigenous customs, domestic life, and religious beliefs.

Pelleprat portrays the Indigenous inhabitants with clarity and sympathy. They are “without guile or malice… and capable of every good doctrine… They are neither cruel nor treacherous, as some have claimed; rather they are generous and easily moved to affection when treated with kindness.” He notes the Galibis skill in painting and weaving: “They take great care in painting their bodies and in making their cotton cloths, which they dye with beautiful colors.”

The author records local fishing and hunting practices, the use of pirogues (canoes) along the coasts, and the construction of dwellings raised above ground: “They live by fish and roots, in houses built upon poles to guard against the waters and the reptiles.”

He marvels at the beauty and richness of South America: its landscape, flora and fauna: “These islands are clothed with great forests, watered by innumerable streams, and so full of fruits that one may live there almost without toil; the trees of these islands bear fruit twice a year, and the soil is so rich that it needs only to be turned over to yield harvests beyond expectation... yet behind this abundance lie continual dangers, both from the climate and from the passions of men.” (p. 8)

The Galibi Language

Pelleprat’s introduction to the Galibi language is one of the earliest printed attempts to describe and translate a South American Indigenous language. He explains the purpose of understanding Galibi: “I have composed a small grammar and vocabulary of the Galibi language, so that our Fathers who shall come after me may speak to these peoples in their own words and more easily win their souls to God.”

Pelleprat opens by justifying his study as a means to conversion, writing that “the barbarous nations… are so docile and so well disposed to receive the Gospel that they await only its preaching.” His goal is not philological in the modern sense but practical: to prepare future missionaries to communicate Christian doctrine. Even so, his careful observations show an emerging recognition of linguistic structure. He notes that “this language has its own rules, its order, and its way of composing words,” an acknowledgment that Amerindian languages were coherent systems rather than the “corrupted” or “primitive” speech often imagined by Europeans.

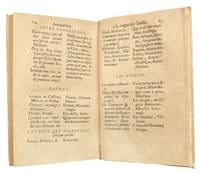

The Introduction proceeds systematically, identifying letters, pronunciation, and basic grammar before offering a brief bilingual vocabulary. Pelleprat outlines nouns, pronouns, and verb forms, and includes everyday expressions drawn from conversation. The vocabulary reveals the priorities of the missionary encounter, pairing religious and material terms: “God” and “Devil,” “soul,” “heaven,” and “earth,” alongside “river,” “house,” and “friend.” Through such juxtapositions, the work translates the Christian world into the idiom of local experience. Pelleprat also recognizes the limits of his own learning, admitting that he “has gathered what he could learn from the natives themselves” and that the book is only a “first attempt.”

An overview of the work:

First Part — The Islands of America

Chapter I. The Mission of the Islands of America and Its Beginning.

Pelleprat opens with the Jesuits’ first arrival at Martinique and their efforts to organize pastoral life amid the exuberance and peril of the Antilles. He contrasts the region’s apparent ease with the moral and climatic dangers confronting its settlers. The founding of chapels, the teaching of catechism, and the first baptisms mark the establishment of a fragile but enduring Christian community sustained by zeal and endurance:

Chapter II. The Mission of Guadeloupe and Saint Christopher.

This chapter traces the Jesuits’ expansion to Guadeloupe and Saint Christopher (St Kitts), emphasizing spiritual poverty and devotion rather than material resources. The Fathers built their first church upon the shore and extended ministry to both colonists and enslaved peoples. Their work joined liturgy with the rhythm of the sea, establishing visible order amid frontier uncertainty:

“We carried with us neither gold nor silver, but the Cross of Christ and a heart desirous only to win souls. With this we founded our first church on the edge of the sea, the waves serving us for organ and bells.” (p. 17)

Chapter III. The Mission to the Neighboring Islands.

Temporary voyages to smaller islands display the itinerant and sacrificial nature of Jesuit labor. Navigating reefs and storms, the Fathers rowed through the night to reach even a single soul awaiting baptism. Each landing combined pastoral urgency with maritime peril, illustrating the missionary’s union of courage and charity:

“The sea, strewn with reefs and currents, seemed to conspire against our enterprise; but the zeal of charity fears neither the waves nor death. Often we rowed whole nights by the light of the moon to reach an island where one child awaited baptism.” (p. 25)

Chapter IV. The Enslaved People and Their Conversion.

Pelleprat describes the catechization of enslaved Africans and the profound moral changes observed after baptism. The Jesuits taught prayers and confession, emphasizing chastity and honesty as signs of genuine conversion. Their accounts blend pastoral pride with human sympathy, presenting individual stories of resistance and virtue as proofs of faith’s transforming power:

“It is difficult to describe the change that is seen in the customs of the enslaved after their baptism; for although they have been reared in brutishness, many become so chaste and honest when they are Christians that they would rather die than commit the least indecency.” (p. 33)

“A savage woman, being importuned to evil by a Frenchman on the island of Saint Christopher, declared that she would rather die than commit so wicked an act, and, being unable otherwise to defend herself, struck the libertine with a firebrand so that he withdrew in shame.” (p. 34)

Chapter V. The Irish Mission.

The author turns to the dispersed Irish Catholics exiled under English authority, who sought out the Jesuits for Mass and confession. Their devotion and tears at the return of the sacraments reveal the wide moral reach of the mission, uniting the oppressed of Europe and the colonized of America under one pastoral care. Pelleprat also recounts the secret ministry carried out among Irish Catholics living under English supervision and the extraordinary virtue of an Irish girl raised in disguise to preserve her chastity. These episodes illustrate the clandestine heroism and moral idealism that marked the Jesuit presence in the islands:

“The poor Irish Catholics, scattered and despised, came to us as to their own fathers, their eyes full of tears for having so long been deprived of the Sacrifice of the Mass.” (p. 40)

“I cannot omit the victory that a young Irish girl won over the weakness of her sex… This girl had come very young to America, and her father, to protect her, had disguised her and raised her in the dress of a boy.” (pp. 49–50)

Chapter VI. Spiritual Fruits and Change of Conduct.

Pelleprat recounts how conversion altered conduct during epidemics and famine. Converts hastened to confession and communion, preferring reconciliation to survival. Their fervor surpassed that of many Europeans, revealing that faith had taken deeper root among those newly baptized than among the settlers themselves:

“In the time of pestilence, when even the air seemed to breathe death, our new Christians came in great numbers to confession and communion, choosing rather to die reconciled to God than to live without His grace.” (p. 47)

“The Natives and Negroes gave example to the French, for they prayed aloud and with tears while many of our countrymen blasphemed.” (p. 49)

Chapter VII. The Conduct of the Fathers Toward the Enslaved and Indigenous Peoples.

The first part concludes with a description of Jesuit pedagogy and linguistic adaptation. The Fathers prepared catechisms and prayers in local idioms, aligning language itself to the work of grace. Such translation gave permanence to faith and dignity to its new speakers:

“We composed for them prayers in their own speech, so that their lips, once accustomed to invoke idols, might now praise the true God.” (p. 52)

Second Part — The Mainland of South America

Chapter I. The First Voyage of Father Méland to the Mainland and Description of the Country.

The mainland section begins with Father Denis Méland’s journey to Guiana. Pelleprat’s natural history renders the landscape a theatre of perpetual fertility and divine harmony. Vast rivers, boundless forests, and equable air testify to providence and to the promise of new conversions within this unspoiled creation:

“The rivers here are broader than many seas, their waters dark as ink under the forest’s shadow. The land breathes a perpetual spring; trees bear fruit without ceasing, and the air is so temperate that one would think Nature had chosen this region for her rest.” (p. 60)

Chapter II. The Peoples of the Mainland, Their Customs, and Disposition to Receive the Faith.

Here Pelleprat records the manners, dwellings, and ceremonies of the Guianese nations. His tone is one of respect and curiosity; hospitality, he notes, is their highest virtue. Physical description mingles with moral judgment, portraying these peoples as orderly, generous, and receptive to instruction:

“They are of good stature, well-formed, their countenance open and agreeable. Their huts are made of palm leaves, their hammocks of woven cotton, their vessels of baked clay painted with strange figures.” (p. 67)

“When we entered their villages, they offered us cassava bread and the drink of their country, pressing us to sit in their hammocks, which they esteem as the greatest courtesy.” (p. 69)

Chapter III. The State of the Mission and the Difficulties Encountered.

The missionaries confront disease, exhaustion, and isolation while pressing inland through forest and flood. Every hardship is redeemed by the baptism of a single child. Pelleprat’s prose here reaches its starkest simplicity, embodying the theology of labor and perseverance that defines the Jesuit vocation:

“We walked whole days through flooded forests, our cassocks torn by thorns, our food spoiled by the rain; yet no labor seemed too great when we saw one child receive baptism.” (p. 76)

Chapter IV. The Advantages and Wonders of the Country.

The Relation pauses for a hymn to the fertility and brilliance of Guiana. Its fields produce without tillage, its rivers teem with enormous fish, and its forests glitter with birds whose colors rival the rainbow. Natural abundance becomes a metaphor for spiritual readiness: the earth itself seems to await cultivation by faith:

“The earth yields fruits without tillage; the rivers abound in fish of marvelous size; the woods echo with the cry of birds whose plumage surpasses the rainbow in brightness.” (p. 82)

Chapter V. Continuation of the Same Subject.

Pelleprat continues his natural observations, listing marvels unknown in Europe with the calm precision of a naturalist and the awe of a priest. His tone joins curiosity to reverence, interpreting wonder as testimony of divine invention:

“I saw serpents with wings like bats, and fish that fly above the water; trees whose leaves close at night as if they slept, and others that exude milk when cut.” (p. 88)

Chapter VI. The Indigenous Peoples, Their Ceremonies, and Their Government.

This chapter outlines the political and moral order of Indigenous societies. Government, Pelleprat notes, is communal and tempered by reason; decisions are made in council and guided by age or valor. He records funerary rites with sympathetic precision, emphasizing their coherence and solemnity:

“Their government is gentle; they obey the oldest or the bravest, and all decisions are taken in council, with much shouting but little injustice.” (p. 92)

“When one dies, they burn his hammock and his weapons, believing that he will find them again beyond the river of souls.” (p. 93)

Chapter VII. Beliefs and Superstitions, and the Means of Overcoming Them.

The final chapter surveys Indigenous cosmology and the Jesuit method of persuasion. Rather than destroying idols by force, the Fathers sought to redirect belief toward its divine origin. The narrative ends in a tone of reconciliation—pagan reverence transformed into Christian wonder:

“They believe that the souls of the dead pass into certain birds and beasts; thus they spare the heron and the serpent, which they hold as sacred.” (p. 98)

“We destroyed their idols, not by force but by patience; showing them that the thunder they feared obeyed the same God who made them.” (p. 100)

Further reading:

Ouellet, Réal, éd. Pierre Pelleprat: Relation des missions des pères de la Compagnie de Jésus dans les îles et dans la terre ferme de l’Amérique méridionale (1655). Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2013; Ouellet, Réal, and Marc-André Bernier, eds. Pierre Pelleprat’s Accounts of the Jesuit Missions in the Antilles and in Guiana (1655). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014.

Of special importance is the third part of the work: the author’s grammar and vocabulary of the Galibi language, one of the earliest printed studies of a South American Indigenous language. Pelleprat explains the purpose of understanding Galibi: “I have composed a small grammar and vocabulary of the Galibi language, so that our Fathers who shall come after me may speak to these peoples in their own words and more easily win their souls to God.”

In 1651, Pierre Pelleprat was sent from France to the Antilles, joining Fathers Denys Mesland, François Gueymeu, and Guillaume Aubergeon. The Jesuits served the indigenous Amerindians, enslaved Africans, and Irish and French settlers. Two years later, Pelleprat and Mesland sailed for the mainland, where they established a mission on the Guarapiche River near the Gulf of Paria. After Mesland’s departure was, Pelleprat remained alone, continuing his missionary work and studying the local language. Illness forced him to return to the islands in 1654. He petitioned to return to Europe but was denied and instead lived out the remainder of his life in Mexico, dying at Puebla de los Angeles in 1667.

The preface outlines the establishment of the Jesuit mission in the French Caribbean following the founding of Martinique and Guadeloupe in 1635. Pelleprat recounts the arrival of the Jesuits and their efforts to learn the native languages in order to communicate doctrine, record confessions, and translate prayers. His descriptions of the climate, geography, and local governance of the islands are accompanied by remarks on Indigenous customs, domestic life, and religious beliefs.

Pelleprat portrays the Indigenous inhabitants with clarity and sympathy. They are “without guile or malice… and capable of every good doctrine… They are neither cruel nor treacherous, as some have claimed; rather they are generous and easily moved to affection when treated with kindness.” He notes the Galibis skill in painting and weaving: “They take great care in painting their bodies and in making their cotton cloths, which they dye with beautiful colors.”

The author records local fishing and hunting practices, the use of pirogues (canoes) along the coasts, and the construction of dwellings raised above ground: “They live by fish and roots, in houses built upon poles to guard against the waters and the reptiles.”

He marvels at the beauty and richness of South America: its landscape, flora and fauna: “These islands are clothed with great forests, watered by innumerable streams, and so full of fruits that one may live there almost without toil; the trees of these islands bear fruit twice a year, and the soil is so rich that it needs only to be turned over to yield harvests beyond expectation... yet behind this abundance lie continual dangers, both from the climate and from the passions of men.” (p. 8)

The Galibi Language

Pelleprat’s introduction to the Galibi language is one of the earliest printed attempts to describe and translate a South American Indigenous language. He explains the purpose of understanding Galibi: “I have composed a small grammar and vocabulary of the Galibi language, so that our Fathers who shall come after me may speak to these peoples in their own words and more easily win their souls to God.”

Pelleprat opens by justifying his study as a means to conversion, writing that “the barbarous nations… are so docile and so well disposed to receive the Gospel that they await only its preaching.” His goal is not philological in the modern sense but practical: to prepare future missionaries to communicate Christian doctrine. Even so, his careful observations show an emerging recognition of linguistic structure. He notes that “this language has its own rules, its order, and its way of composing words,” an acknowledgment that Amerindian languages were coherent systems rather than the “corrupted” or “primitive” speech often imagined by Europeans.

The Introduction proceeds systematically, identifying letters, pronunciation, and basic grammar before offering a brief bilingual vocabulary. Pelleprat outlines nouns, pronouns, and verb forms, and includes everyday expressions drawn from conversation. The vocabulary reveals the priorities of the missionary encounter, pairing religious and material terms: “God” and “Devil,” “soul,” “heaven,” and “earth,” alongside “river,” “house,” and “friend.” Through such juxtapositions, the work translates the Christian world into the idiom of local experience. Pelleprat also recognizes the limits of his own learning, admitting that he “has gathered what he could learn from the natives themselves” and that the book is only a “first attempt.”

An overview of the work:

First Part — The Islands of America

Chapter I. The Mission of the Islands of America and Its Beginning.

Pelleprat opens with the Jesuits’ first arrival at Martinique and their efforts to organize pastoral life amid the exuberance and peril of the Antilles. He contrasts the region’s apparent ease with the moral and climatic dangers confronting its settlers. The founding of chapels, the teaching of catechism, and the first baptisms mark the establishment of a fragile but enduring Christian community sustained by zeal and endurance:

Chapter II. The Mission of Guadeloupe and Saint Christopher.

This chapter traces the Jesuits’ expansion to Guadeloupe and Saint Christopher (St Kitts), emphasizing spiritual poverty and devotion rather than material resources. The Fathers built their first church upon the shore and extended ministry to both colonists and enslaved peoples. Their work joined liturgy with the rhythm of the sea, establishing visible order amid frontier uncertainty:

“We carried with us neither gold nor silver, but the Cross of Christ and a heart desirous only to win souls. With this we founded our first church on the edge of the sea, the waves serving us for organ and bells.” (p. 17)

Chapter III. The Mission to the Neighboring Islands.

Temporary voyages to smaller islands display the itinerant and sacrificial nature of Jesuit labor. Navigating reefs and storms, the Fathers rowed through the night to reach even a single soul awaiting baptism. Each landing combined pastoral urgency with maritime peril, illustrating the missionary’s union of courage and charity:

“The sea, strewn with reefs and currents, seemed to conspire against our enterprise; but the zeal of charity fears neither the waves nor death. Often we rowed whole nights by the light of the moon to reach an island where one child awaited baptism.” (p. 25)

Chapter IV. The Enslaved People and Their Conversion.

Pelleprat describes the catechization of enslaved Africans and the profound moral changes observed after baptism. The Jesuits taught prayers and confession, emphasizing chastity and honesty as signs of genuine conversion. Their accounts blend pastoral pride with human sympathy, presenting individual stories of resistance and virtue as proofs of faith’s transforming power:

“It is difficult to describe the change that is seen in the customs of the enslaved after their baptism; for although they have been reared in brutishness, many become so chaste and honest when they are Christians that they would rather die than commit the least indecency.” (p. 33)

“A savage woman, being importuned to evil by a Frenchman on the island of Saint Christopher, declared that she would rather die than commit so wicked an act, and, being unable otherwise to defend herself, struck the libertine with a firebrand so that he withdrew in shame.” (p. 34)

Chapter V. The Irish Mission.

The author turns to the dispersed Irish Catholics exiled under English authority, who sought out the Jesuits for Mass and confession. Their devotion and tears at the return of the sacraments reveal the wide moral reach of the mission, uniting the oppressed of Europe and the colonized of America under one pastoral care. Pelleprat also recounts the secret ministry carried out among Irish Catholics living under English supervision and the extraordinary virtue of an Irish girl raised in disguise to preserve her chastity. These episodes illustrate the clandestine heroism and moral idealism that marked the Jesuit presence in the islands:

“The poor Irish Catholics, scattered and despised, came to us as to their own fathers, their eyes full of tears for having so long been deprived of the Sacrifice of the Mass.” (p. 40)

“I cannot omit the victory that a young Irish girl won over the weakness of her sex… This girl had come very young to America, and her father, to protect her, had disguised her and raised her in the dress of a boy.” (pp. 49–50)

Chapter VI. Spiritual Fruits and Change of Conduct.

Pelleprat recounts how conversion altered conduct during epidemics and famine. Converts hastened to confession and communion, preferring reconciliation to survival. Their fervor surpassed that of many Europeans, revealing that faith had taken deeper root among those newly baptized than among the settlers themselves:

“In the time of pestilence, when even the air seemed to breathe death, our new Christians came in great numbers to confession and communion, choosing rather to die reconciled to God than to live without His grace.” (p. 47)

“The Natives and Negroes gave example to the French, for they prayed aloud and with tears while many of our countrymen blasphemed.” (p. 49)

Chapter VII. The Conduct of the Fathers Toward the Enslaved and Indigenous Peoples.

The first part concludes with a description of Jesuit pedagogy and linguistic adaptation. The Fathers prepared catechisms and prayers in local idioms, aligning language itself to the work of grace. Such translation gave permanence to faith and dignity to its new speakers:

“We composed for them prayers in their own speech, so that their lips, once accustomed to invoke idols, might now praise the true God.” (p. 52)

Second Part — The Mainland of South America

Chapter I. The First Voyage of Father Méland to the Mainland and Description of the Country.

The mainland section begins with Father Denis Méland’s journey to Guiana. Pelleprat’s natural history renders the landscape a theatre of perpetual fertility and divine harmony. Vast rivers, boundless forests, and equable air testify to providence and to the promise of new conversions within this unspoiled creation:

“The rivers here are broader than many seas, their waters dark as ink under the forest’s shadow. The land breathes a perpetual spring; trees bear fruit without ceasing, and the air is so temperate that one would think Nature had chosen this region for her rest.” (p. 60)

Chapter II. The Peoples of the Mainland, Their Customs, and Disposition to Receive the Faith.

Here Pelleprat records the manners, dwellings, and ceremonies of the Guianese nations. His tone is one of respect and curiosity; hospitality, he notes, is their highest virtue. Physical description mingles with moral judgment, portraying these peoples as orderly, generous, and receptive to instruction:

“They are of good stature, well-formed, their countenance open and agreeable. Their huts are made of palm leaves, their hammocks of woven cotton, their vessels of baked clay painted with strange figures.” (p. 67)

“When we entered their villages, they offered us cassava bread and the drink of their country, pressing us to sit in their hammocks, which they esteem as the greatest courtesy.” (p. 69)

Chapter III. The State of the Mission and the Difficulties Encountered.

The missionaries confront disease, exhaustion, and isolation while pressing inland through forest and flood. Every hardship is redeemed by the baptism of a single child. Pelleprat’s prose here reaches its starkest simplicity, embodying the theology of labor and perseverance that defines the Jesuit vocation:

“We walked whole days through flooded forests, our cassocks torn by thorns, our food spoiled by the rain; yet no labor seemed too great when we saw one child receive baptism.” (p. 76)

Chapter IV. The Advantages and Wonders of the Country.

The Relation pauses for a hymn to the fertility and brilliance of Guiana. Its fields produce without tillage, its rivers teem with enormous fish, and its forests glitter with birds whose colors rival the rainbow. Natural abundance becomes a metaphor for spiritual readiness: the earth itself seems to await cultivation by faith:

“The earth yields fruits without tillage; the rivers abound in fish of marvelous size; the woods echo with the cry of birds whose plumage surpasses the rainbow in brightness.” (p. 82)

Chapter V. Continuation of the Same Subject.

Pelleprat continues his natural observations, listing marvels unknown in Europe with the calm precision of a naturalist and the awe of a priest. His tone joins curiosity to reverence, interpreting wonder as testimony of divine invention:

“I saw serpents with wings like bats, and fish that fly above the water; trees whose leaves close at night as if they slept, and others that exude milk when cut.” (p. 88)

Chapter VI. The Indigenous Peoples, Their Ceremonies, and Their Government.

This chapter outlines the political and moral order of Indigenous societies. Government, Pelleprat notes, is communal and tempered by reason; decisions are made in council and guided by age or valor. He records funerary rites with sympathetic precision, emphasizing their coherence and solemnity:

“Their government is gentle; they obey the oldest or the bravest, and all decisions are taken in council, with much shouting but little injustice.” (p. 92)

“When one dies, they burn his hammock and his weapons, believing that he will find them again beyond the river of souls.” (p. 93)

Chapter VII. Beliefs and Superstitions, and the Means of Overcoming Them.

The final chapter surveys Indigenous cosmology and the Jesuit method of persuasion. Rather than destroying idols by force, the Fathers sought to redirect belief toward its divine origin. The narrative ends in a tone of reconciliation—pagan reverence transformed into Christian wonder:

“They believe that the souls of the dead pass into certain birds and beasts; thus they spare the heron and the serpent, which they hold as sacred.” (p. 98)

“We destroyed their idols, not by force but by patience; showing them that the thunder they feared obeyed the same God who made them.” (p. 100)

Further reading:

Ouellet, Réal, éd. Pierre Pelleprat: Relation des missions des pères de la Compagnie de Jésus dans les îles et dans la terre ferme de l’Amérique méridionale (1655). Québec: Les Presses de l’Université Laval, 2013; Ouellet, Réal, and Marc-André Bernier, eds. Pierre Pelleprat’s Accounts of the Jesuit Missions in the Antilles and in Guiana (1655). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2014.