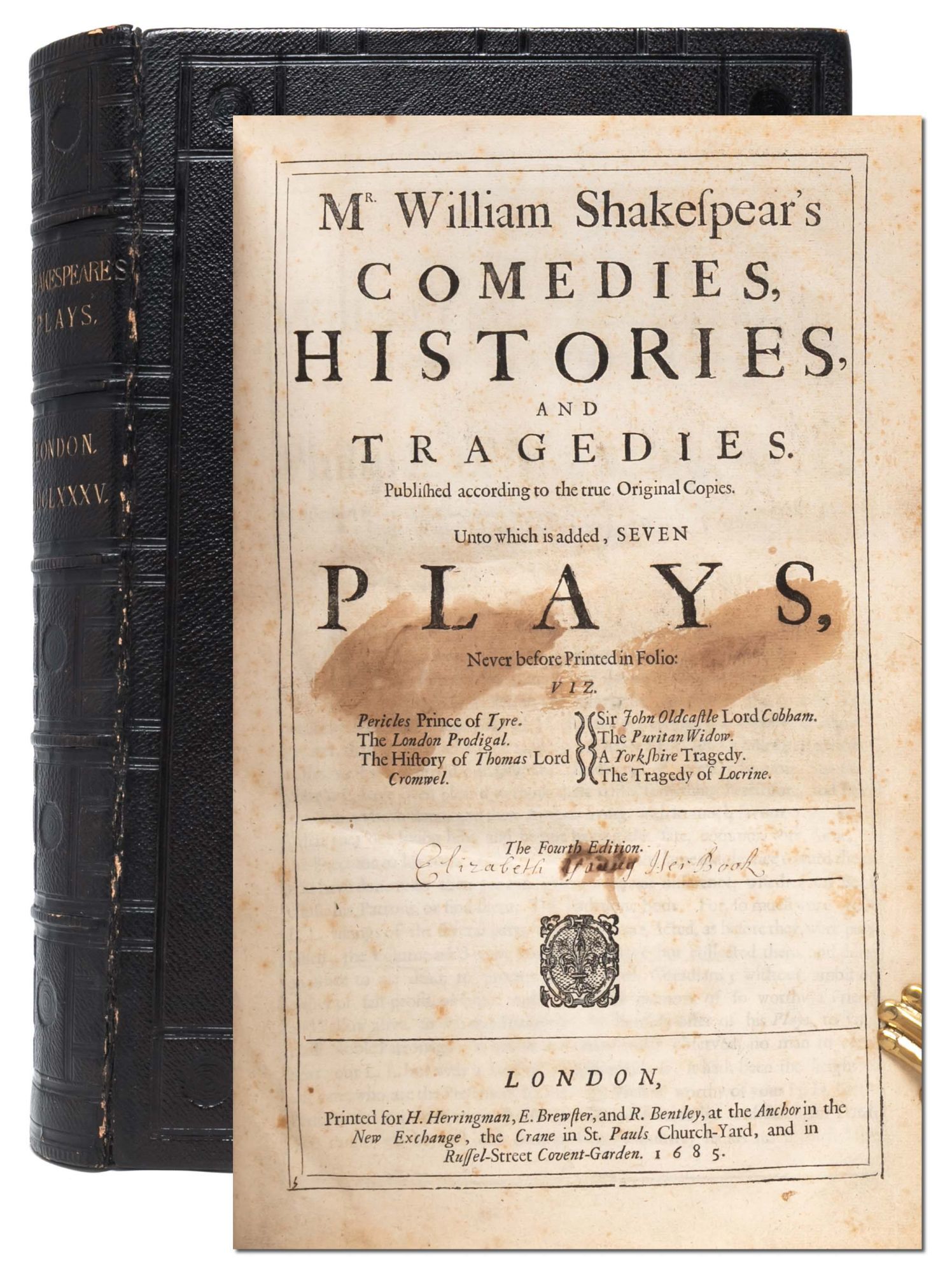

Comedies, Histories and Tragedies. Published according to the true Original Copies. Unto which is added, Seven Plays, Never before Printed in Folio…

- London: for H. Herringman, E. Brewster, and R. Bentley, 1685

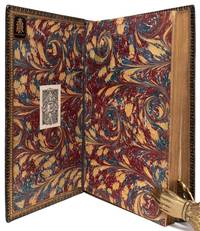

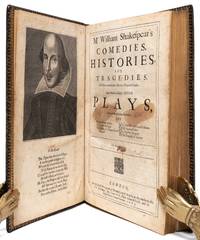

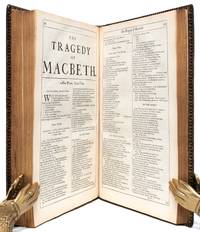

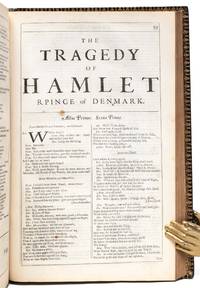

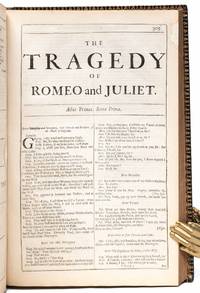

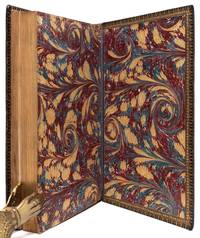

London: for H. Herringman, E. Brewster, and R. Bentley, 1685. Fourth folio. London: for H. Herringman, E. Brewster, and R. Bentley, 1685. Fourth folio. Folio (357 x 228 mm). Bound in a handsome nineteenth-century Victorian full black morocco binding. Boards stamped in blind, spine titled in gilt, with intricate gilt turn-ins. All edges gilt. Marbled end papers. Engraved portrait by Martin Droeshout above the verses “To the Reader” on verso of the first leaf, double column text within typographical rules, woodcut initials. Minor wear or scuffing to the joints and spine ends. Title page with ink stains and minor foxing to the frontispiece. One leaf inserted from another genuine copy of the 4th folio (leaf *ccc6, page 300 in Titus Andronicus), but otherwise a complete and honest copy of the book. Minor foxing, staining or rust holes to a handful of leaves (rust holes affecting a few letters on E2 and Cccc), a few leaves with printer’s flaws (the page number on Ff4 and leaves Oo3-4 where the ink impression gets fainter). A few minor marginal repairs to small chips or tears at the edges of the leaves (T3, Ll1, *Ddd3, Nnn6, Ppp6, Aaaa3), but no text affected or supplied, and no margins extended. In all a very attractive and authentic example of one of the greatest works of literature of all time.

With distinguished provenance, starting with the early woman’s ownership signature of Elizabeth Young to the title-page. Young also owned copies of other seventeenth-century editions of Shakespeare: her ownership signature appears in a bound volume that includes Julius Caesar (1691) and Othello (1695), now held at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Young’s inscription in that volume reveals that she inherited it from her “Grandmother Bathurst" (possibly of the aristocratic Bathurst family); a second inscription, “Frances Young Her Book 1728,” indicates that Young’s daughter inherited the book in turn. Also with the bookplate of Thomas Jefferson McKee on the front pastedown, whose exceptional collection (including this book) was auctioned at Anderson’s, NY, April 29-30, 1901. And with the morocco monogram bookplate of Annie Burr Jennings (1855-1939) of Fairfield, CT, great aunt of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Needless to say, the fourth folio contains some of the finest works ever written in English, and continues the distinguished legacy of Shakespearean publishing that began with the early quarto editions and the monumental first folio of 1623. The first folio was edited by John Heminge (d. 1630) and Henry Condell (d. 1627), and seven plays were added in 1664 by Philip Chetwin (d. 1680) for the second issue of the third folio, of which only one, Pericles, is in part the authentic work of Shakespeare. This fourth folio was a straight reprint of the second issue of the third folio, issued by Henry Herringman in conjunction with other booksellers, part of Herringman’s larger project of publishing pre-Restoration playwrights in folio.

The most immediately striking aspect of the fourth folio is its height: Herringman used a larger paper size and a larger, more liberally spaced font, to grand effect. The text was set from a copy of the third folio divided into three portions and sent to three different London printers. The Comedies were printed by Robert Roberts, the Histories and first four Tragedies by Robert Everingham, and the remaining Tragedies by Everingham’s former master printer, John Macock; the three parts are separately paginated. There were three issues, with slightly different imprints, and no known precedence between the three issues. Macock printed the title page for Herringman’s copies, “to be sold by Joseph Knight and Francis Saunders,” the booksellers to whom Herringman had entrusted his retail business. Roberts printed the title pages for the other issues from a single type setting, with either three booksellers named, as here, or with four, adding Richard Chiswell.

The fourth folio remained the favored edition among collectors until the mid-eighteenth century. It was also the basis for the majority of the eighteenth-century editions of Shakespeare, including those published by Jacob Tonson (1655 – 1736) and his successors, who had purchased the rights to some of the plays from Herringman’s heirs. The Tonson editions were “highly successful in popularizing the plays” for a new generation of readers and performers (Oxford DNB). It was the fourth folio, then, that ensured continued interest in Shakespeare’s work throughout the eighteenth century and carried his legacy into the modern era.

Bartlett 123; Gregg III, p. 1121; Jaggard, p. 497; Pforzheimer 910; Wing S-2915. For identification of the printers, see Christopher N. Warren et al., “Who Rpinted [sic] Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio?” Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 74, Issue 2, Summer 2023.

With distinguished provenance, starting with the early woman’s ownership signature of Elizabeth Young to the title-page. Young also owned copies of other seventeenth-century editions of Shakespeare: her ownership signature appears in a bound volume that includes Julius Caesar (1691) and Othello (1695), now held at the Folger Shakespeare Library. Young’s inscription in that volume reveals that she inherited it from her “Grandmother Bathurst" (possibly of the aristocratic Bathurst family); a second inscription, “Frances Young Her Book 1728,” indicates that Young’s daughter inherited the book in turn. Also with the bookplate of Thomas Jefferson McKee on the front pastedown, whose exceptional collection (including this book) was auctioned at Anderson’s, NY, April 29-30, 1901. And with the morocco monogram bookplate of Annie Burr Jennings (1855-1939) of Fairfield, CT, great aunt of First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis.

Needless to say, the fourth folio contains some of the finest works ever written in English, and continues the distinguished legacy of Shakespearean publishing that began with the early quarto editions and the monumental first folio of 1623. The first folio was edited by John Heminge (d. 1630) and Henry Condell (d. 1627), and seven plays were added in 1664 by Philip Chetwin (d. 1680) for the second issue of the third folio, of which only one, Pericles, is in part the authentic work of Shakespeare. This fourth folio was a straight reprint of the second issue of the third folio, issued by Henry Herringman in conjunction with other booksellers, part of Herringman’s larger project of publishing pre-Restoration playwrights in folio.

The most immediately striking aspect of the fourth folio is its height: Herringman used a larger paper size and a larger, more liberally spaced font, to grand effect. The text was set from a copy of the third folio divided into three portions and sent to three different London printers. The Comedies were printed by Robert Roberts, the Histories and first four Tragedies by Robert Everingham, and the remaining Tragedies by Everingham’s former master printer, John Macock; the three parts are separately paginated. There were three issues, with slightly different imprints, and no known precedence between the three issues. Macock printed the title page for Herringman’s copies, “to be sold by Joseph Knight and Francis Saunders,” the booksellers to whom Herringman had entrusted his retail business. Roberts printed the title pages for the other issues from a single type setting, with either three booksellers named, as here, or with four, adding Richard Chiswell.

The fourth folio remained the favored edition among collectors until the mid-eighteenth century. It was also the basis for the majority of the eighteenth-century editions of Shakespeare, including those published by Jacob Tonson (1655 – 1736) and his successors, who had purchased the rights to some of the plays from Herringman’s heirs. The Tonson editions were “highly successful in popularizing the plays” for a new generation of readers and performers (Oxford DNB). It was the fourth folio, then, that ensured continued interest in Shakespeare’s work throughout the eighteenth century and carried his legacy into the modern era.

Bartlett 123; Gregg III, p. 1121; Jaggard, p. 497; Pforzheimer 910; Wing S-2915. For identification of the printers, see Christopher N. Warren et al., “Who Rpinted [sic] Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio?” Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 74, Issue 2, Summer 2023.