Collection of Letters Sent from California Prisons, 2006–2015, Including Inmates’ Art and Descriptions of the Inmate Firefighting System

- Eighty letters, ten artworks, and two photographs. Anonymized for writers’ and their families’ privacy, with more informatio

- California , 2015

California, 2015. Eighty letters, ten artworks, and two photographs. Anonymized for writers’ and their families’ privacy, with more information available on request. Overall excellent.. Offered here is a collection of letters and art sent from people incarcerated in the California State Prison system, primarily from a husband (“P.”) and wife (“A.”) to P’s mother and stepfather.

A., who served a shorter sentence than P., worked as an inmate-firefighter. Currently, about twenty to thirty percent of California’s firefighters are incarcerated people, and about ten percent of those are women; they work cutting the fireline, receiving little compensation and at a significantly higher risk of injury than both their non-incarcerated counterparts and other prison laborers. They also are not eligible to become firefighters upon release, due to California’s laws about both employment and EMT certification following a felony conviction.[1] A. writes of her training:

“I’ve been training for camp. Its realy realy hard. This has got to be the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. Well Im gonna make this my last trip to prison well, I hope so anyway.” (January 12, 2009)

She also writes from the field that “Its very hard and dangerouse but I guess Im used to it” (June 6, 2009), with later letters giving more detailed descriptions; for instance:

“Im not in San Diego right now because my crew and my cousins crew got sent to all the fires that are up North =) we left on the 4th and we’ve been on the road and to a couple of fires since I don’t know when we are going back but Im making money! yesterday I worked a 24 hour shift and we got back to have our down time to rest this morning. Its very tireing and hard I felt like I was hiking forever! Right know Im up in Shasta County its beautif up here and I’ve never been this far from home befor.” (August 14, 2009)

A. wanted to save up to buy a car. She wrote that firefighting is “hard work for a dollar a day” (December 14, 2009)—in 2023, the inmate-firefighter pay rate was raised to an astounding 16 to 74 cents per hour with a maximum daily rate of $5.80 to $10.24.[2]

P., on a longer sentence in various higher-security facilities, grappled with boredom, loneliness, and the bureaucracy involved in trying to contact his wife and family. The prisons where he was incarcerated were frequently on lockdown for months at a time, including the Corcoran Substance Abuse Treatment Facility, which locked down in June of 2009 following a gang-related riot. He often describes being hungry and not allowed to go to the commissary, either because of lockdowns or just because “there not letting Hispanics go” (January 30, 2011).

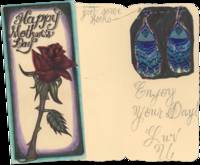

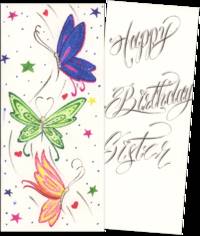

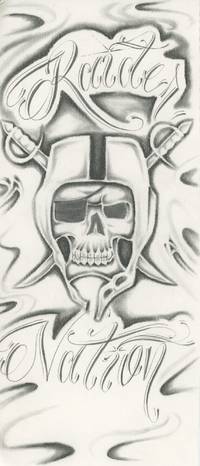

One way he seemed to have dealt with his circumstances was through art. Over time, his package requests—incarcerees can only be sent packages through approved third-party vendors, which contract with prisons—included, alongside toothpaste and deodorant, art supplies and even a typewriter and books on “how to properly write a novel” (January 30, 2011). He mentions copying drawings, and the reader can see him experiment with different handwriting styles in the letters and on envelopes. The art in the collection includes greeting cards with teddy bear, clown—a common character in Chicano art—and nature motifs; a Las Vegas Raiders butterfly (signed “E”, most likely by P.’s cellmate Ernie, for whom drawing is a “little hustle to make money for food and supplies” (January 30)); and a pair of beaded earrings that P. bought for $10 “to some Indian here” (August 25, 2010).

Of interest to scholars of outsider art and incarceration in the California prison system.

[1] Carly Tolin, “Fighting More Than Fires: California’s Inmate Firefighting System Needs Reform,” The Georgetown Environmental Law Review, February 6, 2025.

[2] Doug Melville, “Inmates Can Make Up Nearly A Third Of Those Fighting California Fires,” Forbes, January 9, 2025.

A., who served a shorter sentence than P., worked as an inmate-firefighter. Currently, about twenty to thirty percent of California’s firefighters are incarcerated people, and about ten percent of those are women; they work cutting the fireline, receiving little compensation and at a significantly higher risk of injury than both their non-incarcerated counterparts and other prison laborers. They also are not eligible to become firefighters upon release, due to California’s laws about both employment and EMT certification following a felony conviction.[1] A. writes of her training:

“I’ve been training for camp. Its realy realy hard. This has got to be the hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life. Well Im gonna make this my last trip to prison well, I hope so anyway.” (January 12, 2009)

She also writes from the field that “Its very hard and dangerouse but I guess Im used to it” (June 6, 2009), with later letters giving more detailed descriptions; for instance:

“Im not in San Diego right now because my crew and my cousins crew got sent to all the fires that are up North =) we left on the 4th and we’ve been on the road and to a couple of fires since I don’t know when we are going back but Im making money! yesterday I worked a 24 hour shift and we got back to have our down time to rest this morning. Its very tireing and hard I felt like I was hiking forever! Right know Im up in Shasta County its beautif up here and I’ve never been this far from home befor.” (August 14, 2009)

A. wanted to save up to buy a car. She wrote that firefighting is “hard work for a dollar a day” (December 14, 2009)—in 2023, the inmate-firefighter pay rate was raised to an astounding 16 to 74 cents per hour with a maximum daily rate of $5.80 to $10.24.[2]

P., on a longer sentence in various higher-security facilities, grappled with boredom, loneliness, and the bureaucracy involved in trying to contact his wife and family. The prisons where he was incarcerated were frequently on lockdown for months at a time, including the Corcoran Substance Abuse Treatment Facility, which locked down in June of 2009 following a gang-related riot. He often describes being hungry and not allowed to go to the commissary, either because of lockdowns or just because “there not letting Hispanics go” (January 30, 2011).

One way he seemed to have dealt with his circumstances was through art. Over time, his package requests—incarcerees can only be sent packages through approved third-party vendors, which contract with prisons—included, alongside toothpaste and deodorant, art supplies and even a typewriter and books on “how to properly write a novel” (January 30, 2011). He mentions copying drawings, and the reader can see him experiment with different handwriting styles in the letters and on envelopes. The art in the collection includes greeting cards with teddy bear, clown—a common character in Chicano art—and nature motifs; a Las Vegas Raiders butterfly (signed “E”, most likely by P.’s cellmate Ernie, for whom drawing is a “little hustle to make money for food and supplies” (January 30)); and a pair of beaded earrings that P. bought for $10 “to some Indian here” (August 25, 2010).

Of interest to scholars of outsider art and incarceration in the California prison system.

[1] Carly Tolin, “Fighting More Than Fires: California’s Inmate Firefighting System Needs Reform,” The Georgetown Environmental Law Review, February 6, 2025.

[2] Doug Melville, “Inmates Can Make Up Nearly A Third Of Those Fighting California Fires,” Forbes, January 9, 2025.