Collection of Captain Kiyoshi Tanaka, US Military Intelligence Officer Stationed in Japan and Korea

- Approximately 143 items: forty-two letters (twenty-five in Japanese and seventeen in English); seventy-six photographs with twel

- United States and Japan , 1964

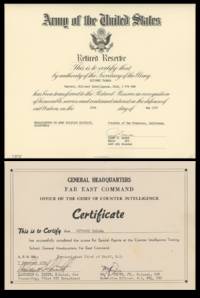

United States and Japan, 1964. Approximately 143 items: forty-two letters (twenty-five in Japanese and seventeen in English); seventy-six photographs with twelve medium-format negatives; eleven pieces of military ephemera; an inscribed handkerchief; and a lacquered wood storage box (8 x 14 x 7 inches) with family crest. Letters and ephemera Near Fine, photographs curled, else excellent; overall excellent to Near Fine.. Kiyoshi Tanaka (1914–2001) was born in Sacramento to parents who immigrated from Japan early in the century. In 1943, he and his parents were interned at the Tule Lake War Relocation Center in northern California. Tanaka joined the military in 1949 and served as a Special Agent with the 115th Counter Intelligence Corps Detachment, a component of the Far East Command, and was stationed in Japan and Korea from 1950 to about 1954. He returned to California and transferred to the Army Reserve in 1956, retiring from the military in 1957.

Offered here is a collection of Tanaka’s correspondence, photographs, and military documents, mainly from the 1950s. The latter are certificates of appointment and training—Tanaka took courses in counterintelligence and martial law—and transfer and discharge documents. According to his correspondence, Tanaka served in both Japan and Korea, though he was mainly stationed in Japan and does not seem to have gone to Korea before 1952. Though the US technically no longer occupied Japan after the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, the accompanying Security Treaty allowed the US military to maintain military bases in the country, which were critical in the Korean War. Tanaka’s photographs appear to have been taken primarily in Japan, and show street scenes, target practice, and some shots of office work.

Tanaka does not appear to have discussed details of his work with his family and friends; most of his correspondence consists of reminiscing with friends, discussing weather and health with family, and reassuring a girlfriend in Japan that his “evils are limited to drinking 2 or 3 beers” (May 17, 1954; translated). Sometimes friends reflect on current events; one writes:

“You, no doubt, have read of strikes and there are still talks of other strikes. We do hope that conditions will become so, so that there will be more settlements without walkouts and the like. Yes, the higher ups always use the Korea situation as a defense but the people in general do not have that close cooperating spirit as there was during the last war.” (February 23, 1951)

Also included in the correspondence are several items from attorney Henry Taketa concerning Tanaka’s attempts to get compensation for himself and his mother via the 1948 Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act. The Act was intended to compensate Japanese Americans for losses incurred when they were interned. Tanaka filed and was rejected several times, first for over $2,000 and then for over $1,500; the government countered that Tanaka and his mother were only owed about $90 total. This would have been a typical experience, as the Act highly restricted what kinds of losses would be compensated and made the process arduous.

Of interest to historians of the Japanese American experience after World War II, and during the Korean War in particular.

Offered here is a collection of Tanaka’s correspondence, photographs, and military documents, mainly from the 1950s. The latter are certificates of appointment and training—Tanaka took courses in counterintelligence and martial law—and transfer and discharge documents. According to his correspondence, Tanaka served in both Japan and Korea, though he was mainly stationed in Japan and does not seem to have gone to Korea before 1952. Though the US technically no longer occupied Japan after the 1951 Treaty of San Francisco, the accompanying Security Treaty allowed the US military to maintain military bases in the country, which were critical in the Korean War. Tanaka’s photographs appear to have been taken primarily in Japan, and show street scenes, target practice, and some shots of office work.

Tanaka does not appear to have discussed details of his work with his family and friends; most of his correspondence consists of reminiscing with friends, discussing weather and health with family, and reassuring a girlfriend in Japan that his “evils are limited to drinking 2 or 3 beers” (May 17, 1954; translated). Sometimes friends reflect on current events; one writes:

“You, no doubt, have read of strikes and there are still talks of other strikes. We do hope that conditions will become so, so that there will be more settlements without walkouts and the like. Yes, the higher ups always use the Korea situation as a defense but the people in general do not have that close cooperating spirit as there was during the last war.” (February 23, 1951)

Also included in the correspondence are several items from attorney Henry Taketa concerning Tanaka’s attempts to get compensation for himself and his mother via the 1948 Japanese American Evacuation Claims Act. The Act was intended to compensate Japanese Americans for losses incurred when they were interned. Tanaka filed and was rejected several times, first for over $2,000 and then for over $1,500; the government countered that Tanaka and his mother were only owed about $90 total. This would have been a typical experience, as the Act highly restricted what kinds of losses would be compensated and made the process arduous.

Of interest to historians of the Japanese American experience after World War II, and during the Korean War in particular.