Collection of Photographs of 1960s Lahore, Taken by an American Family, with Extensive Captions Detailing Their Thoughts on the Locals

- Ninety-four photographs measuring 5 x 3 ½ inches to 2 x 2 inches. Many with manuscript captions verso and some marked recto

- Lahore, Pakistan , 1965

Lahore, Pakistan, 1965. Ninety-four photographs measuring 5 x 3 ½ inches to 2 x 2 inches. Many with manuscript captions verso and some marked recto. Overall excellent to Near Fine.. Photos taken by Denverite Lyman R. Flook, Jr., and his family, with many captioned by his wife Dorothy, documenting their time living in Lahore from 1960 to 1965. Lyman Flook (1921–1993) worked at the engineering firm of Tipton & Kalmach, which in 1960 won a contract to design and construct a link canal system in Pakistan. This was likely related to the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, which determined which Indus Basin rivers would supply water to India and which to Pakistan, and allowed a ten year transition period in which India would supply some of Pakistan’s water while Pakistan built its canal system. While Lyman Flook worked on the canal, Dorothy (1921–2020) taught at the Lahore American School. They and the other American families in Lahore with Tipton & Kalmach left in 1965 after the outbreak of the Indo-Pakistani War.

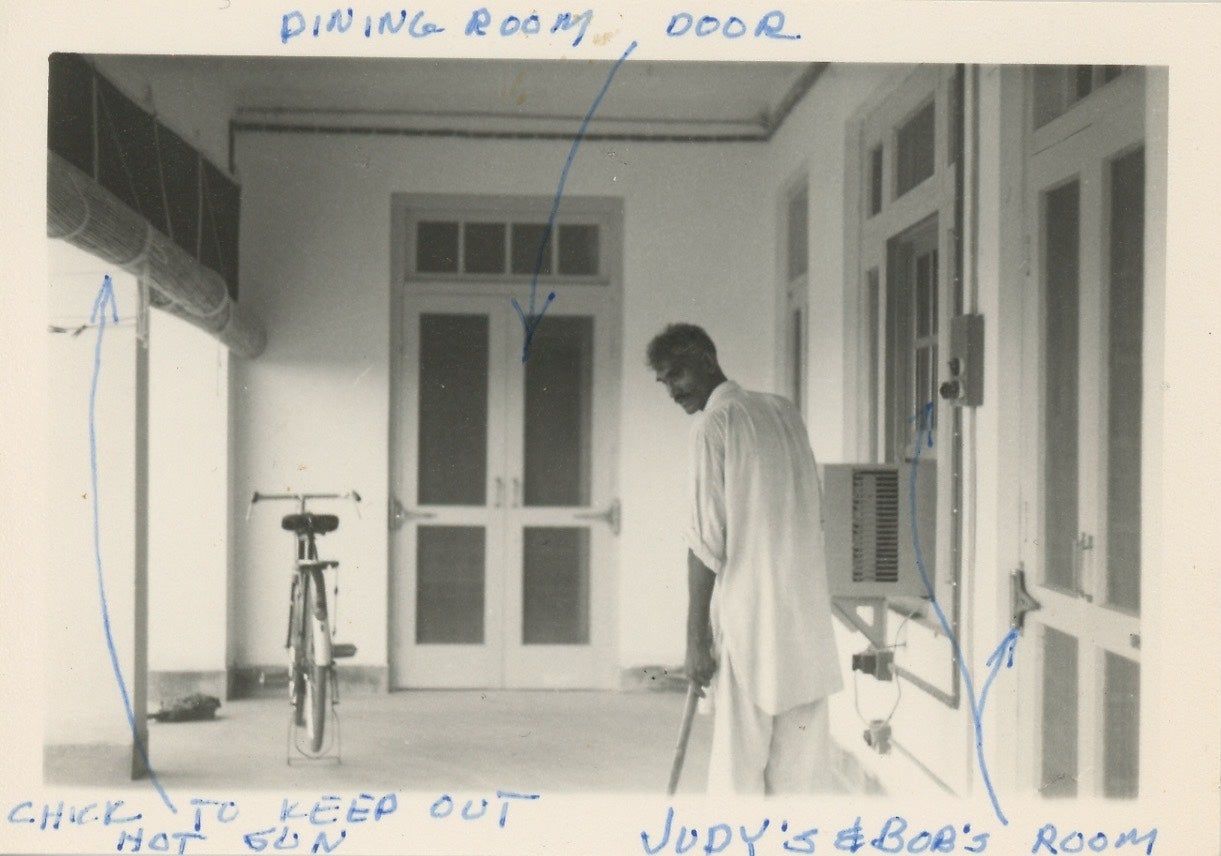

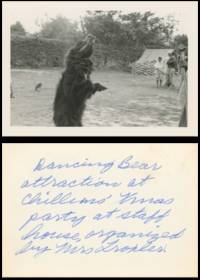

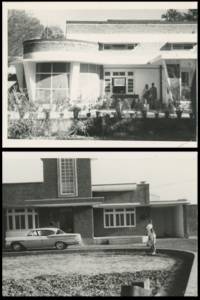

The Flooks lived in a large, stylish house, likely in the upscale WAPDA (i.e., Water And Power Development Authority) Town neighborhood of Lahore. The shots include many of the other American engineers’ families, typically identified by full or at least last name, including the Thiel, Troxler, and Rockwell families. There are Christmas events with Santa and even a child’s birthday party featuring a dancing bear. Most interesting, though, are those of local people and life in Lahore—some portraits of the locals are quite competently and compellingly shot. Most of the Pakistani subjects depicted are servants of the American families: chowkidars (watchmen), ayahs (nursemaids), dhobis (washers), sweepers, and groundskeepers. They are identified by first name in Dorothy Flook’s extensive captions, which also illustrate the relationship between the Americans and their hired labor. For instance, she writes:

“Our New Chowkidar. He was sent over by the Rockwells who wanted to save money doing without one. As soon as it was known they had no chowkidar, things started disappearing from their garage. The locals are always trying to create jobs for each other.”

Of the ayahs, she relates:

“Norma said her ayah asked for overtime pay, saying ‘Mrs Flook, her boss’s wife, was giving it,’ — a dead lie. She and Edie told me to be plenty mean so they won’t be always getting that club for their servants.”

And in one of the most unfriendly captions, she describes their washerman:

“Our Dhobi Boksh. He used to come every day; now he comes every other day. Dumbest looking character you ever saw but he’s surprisingly faithful.”

Others are described as “always underfoot”, “doing nothing”, and “Stealing yet!”.

Of interest to historians of US activities in Pakistan in the 1960s, and relationships between Americans and Pakistanis on the ground.

The Flooks lived in a large, stylish house, likely in the upscale WAPDA (i.e., Water And Power Development Authority) Town neighborhood of Lahore. The shots include many of the other American engineers’ families, typically identified by full or at least last name, including the Thiel, Troxler, and Rockwell families. There are Christmas events with Santa and even a child’s birthday party featuring a dancing bear. Most interesting, though, are those of local people and life in Lahore—some portraits of the locals are quite competently and compellingly shot. Most of the Pakistani subjects depicted are servants of the American families: chowkidars (watchmen), ayahs (nursemaids), dhobis (washers), sweepers, and groundskeepers. They are identified by first name in Dorothy Flook’s extensive captions, which also illustrate the relationship between the Americans and their hired labor. For instance, she writes:

“Our New Chowkidar. He was sent over by the Rockwells who wanted to save money doing without one. As soon as it was known they had no chowkidar, things started disappearing from their garage. The locals are always trying to create jobs for each other.”

Of the ayahs, she relates:

“Norma said her ayah asked for overtime pay, saying ‘Mrs Flook, her boss’s wife, was giving it,’ — a dead lie. She and Edie told me to be plenty mean so they won’t be always getting that club for their servants.”

And in one of the most unfriendly captions, she describes their washerman:

“Our Dhobi Boksh. He used to come every day; now he comes every other day. Dumbest looking character you ever saw but he’s surprisingly faithful.”

Others are described as “always underfoot”, “doing nothing”, and “Stealing yet!”.

Of interest to historians of US activities in Pakistan in the 1960s, and relationships between Americans and Pakistanis on the ground.