Multigenerational Archive of a Pennsylvania Family, Spanning More Than a Century

- 320 items: 276 letters, thirty-eight modern photographs, five CDVs and one cabinet card; with a large amount of unsorted ephemer

- United States, Norway, and Germany , 1960

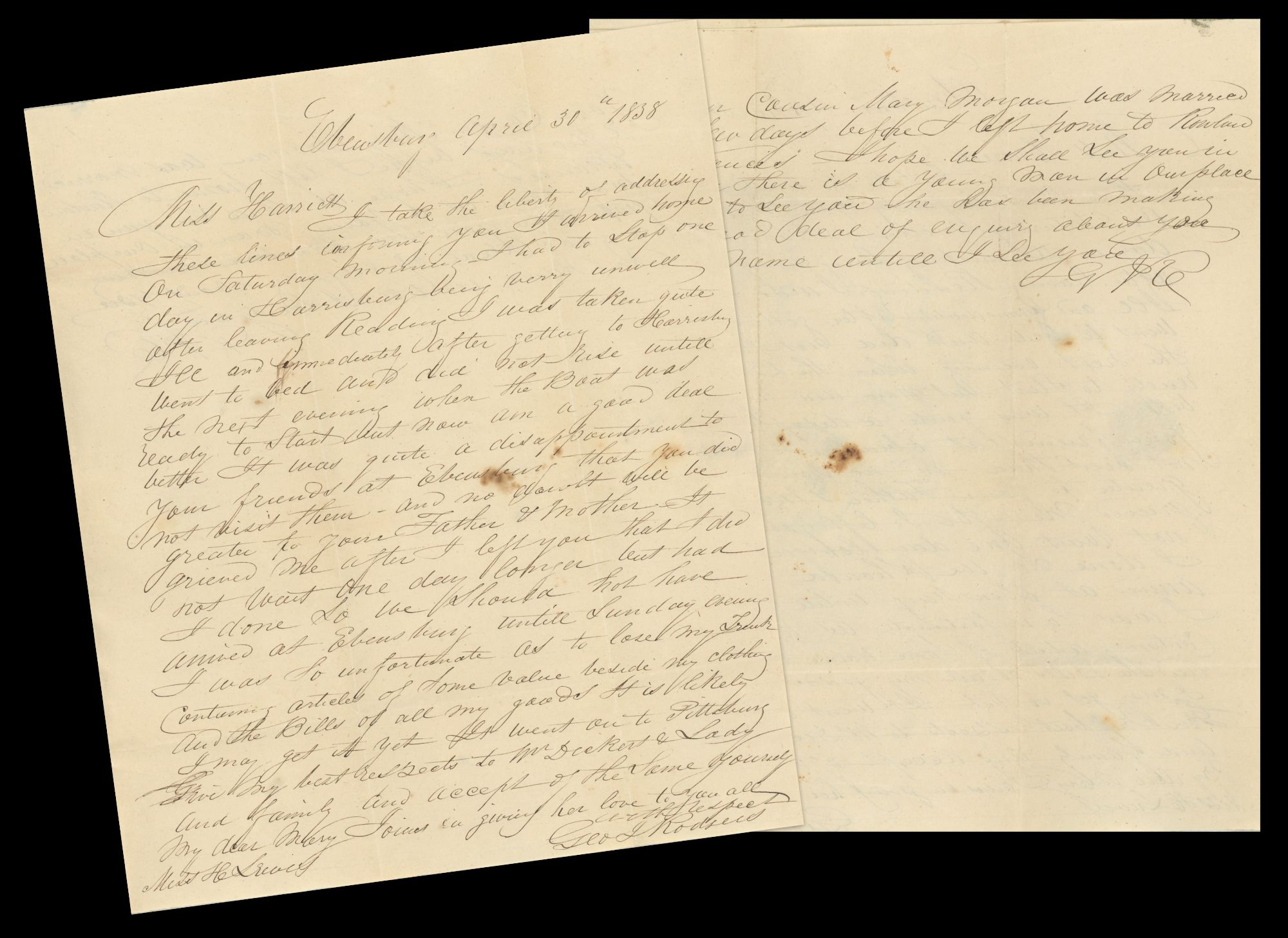

United States, Norway, and Germany, 1960. 320 items: 276 letters, thirty-eight modern photographs, five CDVs and one cabinet card; with a large amount of unsorted ephemera. Of the letters, 198 are from the nineteenth century, with most from the 1840s through 1870s; and seventy-eight are from the twentieth century, with most from the 1940s and 1950s. Excellent.. A broad archive, mainly of letters, spanning over 130 years. The letters were mostly sent between members of the Hill family of Pennsylvania and other families (Lewis, Hosack, and Weeks) that married in. In the nineteenth century, George Hill (1815–1895), his wife Harriet Lewis (1820–1852), and their two oldest daughters Jane Hosack (1842–1878) and Harriet Hill (1844–1928) are the main correspondents; in the twentieth, letters are mainly from Cornelia (1863–1948) and Charlotte (1874–deceased) Lewis, Harriet Lewis’ nieces, and the family of Nancy Weeks (1909–1992), her great-granddaughter-in-law. Weeks also had several correspondents in Europe immediately after World War II.

Earlier letters discuss family affairs, temperance societies, and church business—George Hill was a Presbyterian minister, and writes to his family from trips to the General Assembly. For instance, he describes the 1843 Assembly:

“We have dispatched a good deal of business this week in the Assembly. The question which detained us longest was with regard to the right of Elders to impose hands in the Ordination of Ministers, this was discussed for the greater part of two days, and finally decided against the right to impose. But of all the questions which have yet come before us none has excited so much interest or called forth half the feeling which the question on the approval of the records of the Synod of Pittsburgh did. The committee on the records took exception to the mention of the Synod on the subject of Temperance [...] On this I let them know my mind at considerable length, and in the course of the proceedings voted down the very same proposition which was adopted by the last Gen. Ass. on the subject of Temperance.” (May 27, 1843)

At the same time, Hill was preaching around Pennsylvania and Ohio to raise funds to start the Blairsville Female Seminary, which was open from 1851 to 1913. Among his travel correspondence is an interesting description of antebellum Athens, Ohio:

“On Tuesday morning I rode 6 or 7 miles to Athens [...] which is wholly given over to abolition. This subject is to that people ‘The one thing needful’. It is the law and the gospel; it [is] philanthropy, patriotism, morality and religion. It swallows up everything else and enlists the sympathies & energies of the people to the exclusion of almost everything besides.” (January 29, 1844)

By the outbreak of the Civil War, Jane and Harriet are young adults, and Harriet gets involved with the war effort. She writes to her stepmother, Abigail Hawes:

“I was in sewing for the Soldiers yesterday. I made a Havelock. I guess there were over thirty ladies there sewing. The Bardstown ladies are making clothing for Capt. S[?]’s company. They leave on next Monday. [...] I went in early last Monday morning to see our company off. The flag was presented by Mr Beaumin to Capt. Nesbit. Then Mrs Thompson & Luther Martin presented Testaments & ‘Prayer Books’ (some of Mrs. McAfee’s work) they then marched up to the depot followed by men women & children. Such a sight I never witnessed. Some of the soldiers (large men) cried like children – bade goodbye to every body – men that I never saw before came up & bade me goodbye & then turned their heads away to hide the tears. [...] But to go back to our Sewing Society you ask ‘will they really do anything’? I tell you they really have done something. Made seventy five shirts (& intend making so many more) of blue & red flannel, & forty five or fifty Havelocks, about thirty five towels, eighty pin cushions (or needle books). Then when the company went away the ladies supplied them with either a blanket or a comfort apiece [...] The ladies also intend making bandages or something to fasten tight round their stomachs to keep them from taking dysentery so readily.” (June 4, 1861)

Harriet notes that Abigail doesn’t “seem to be much disturbed about the war” (May 20), though she requests that although “We all admire your patriotism [...] be sure & dont send us an envelope with ‘Death to Traitors’ on it” (June 4).

Other letters from Harriet and Jane discuss school, family, and especially health; a number of deadly diseases were rampant throughout the century, and many letters read as litanies of dead and dying friends and family. The CDVs from this era, mainly taken in studios in Blairsville, seem to be mostly family friends or employees at the Female Seminary; many of the subjects are identified verso.

The family’s letters in the twentieth century are similar, though with less sickness and death, and from more dispersed locations in the US—seemingly few family members remained in Pennsylvania.

One particularly interesting thread is Nancy Weeks’ correspondence with several Europeans immediately after World War II. One is Benjamin Molnar, a Hungarian living in Munich and in the process of emigrating to the US. Molnar describes himself, and continental Europeans generally, as “prejudiced [and] very nationalistic”, and explains that he would prefer to live in the American midwest or west as the “types of people” on the east coast “are rather unamerican looking” (July 14, 1949). He ends up in California, and complains to Weeks that:

“Everybody here seems to be violently pro-negro and pro-Jewish. Jews and negroes are all right I suppose and I have nothing against them but is it a sin for a white man to prefer to live among his own kind?” (December 27, 1949)

On the other end of the spectrum are the Bjelkes, a Norwegian family who write a number of times to Nancy. They describe the Nazi invasion:

“Reidar drove me and the children (7 & 2 years) up in the country, the first day, thinking we would be safe there, he had to leave right away to do his duty of course and we were left alone. Not many days later we were in the middle of the whole war, shooting and bombing all around, then the middle of the nite we had to flee, out in the snow, two children and no place to go, at last I could no more and together with some others we broke the window of a little mountain home and crawled thru, finding the house empty. [...] But the peace was short, not long after some soldiers came and said we must off as the germans would soon be there. Well out in the deep snow again and we struggle thru and at last came to a little mountain farm where we were allowed to stay. But they had little food and for four weeks we starved [...] At last Reidar found us and we wandered our way towards home [...] to Bygdo. Mother had been there all the time and everything had been fine there.” (October 10, 1945)

They also tell Weeks about Oslo during the war, and their experience of the occupation:

“We demonstrated our hate as far as we dared to – by not sitting beside any Germans for example on the car, it went so far that they put up a ticket saying ‘no seat must stay vacant, or we would be arrested.’ The result was that we just stood all the time, then a new ticket came up, we were not aloud to stand. Well I had to jump off the car several times in order not to seat myself beside a uniform. Then they started taking our red caps & scarfs – we, used them as a demonstration you see, & they not only took them off us, but kept them. They even took our red jackets from us if we dared wear them on the street, & so many dared! On our Kings last birthday, during the war, several hundred were arrested because they wore flowers in their buttonholes–, Oh the Germans & Naszi were so childish.” (May 11, 1945)

They also describe the difficulties of postwar life, including the dangers of unexploded ordnance left around the area, which stop the ferries from running to Oslo and injure the family’s young son Per.

Overall, the archive is notable for its breadth, spanning at least four generations of a family and many historical eras and events.

Earlier letters discuss family affairs, temperance societies, and church business—George Hill was a Presbyterian minister, and writes to his family from trips to the General Assembly. For instance, he describes the 1843 Assembly:

“We have dispatched a good deal of business this week in the Assembly. The question which detained us longest was with regard to the right of Elders to impose hands in the Ordination of Ministers, this was discussed for the greater part of two days, and finally decided against the right to impose. But of all the questions which have yet come before us none has excited so much interest or called forth half the feeling which the question on the approval of the records of the Synod of Pittsburgh did. The committee on the records took exception to the mention of the Synod on the subject of Temperance [...] On this I let them know my mind at considerable length, and in the course of the proceedings voted down the very same proposition which was adopted by the last Gen. Ass. on the subject of Temperance.” (May 27, 1843)

At the same time, Hill was preaching around Pennsylvania and Ohio to raise funds to start the Blairsville Female Seminary, which was open from 1851 to 1913. Among his travel correspondence is an interesting description of antebellum Athens, Ohio:

“On Tuesday morning I rode 6 or 7 miles to Athens [...] which is wholly given over to abolition. This subject is to that people ‘The one thing needful’. It is the law and the gospel; it [is] philanthropy, patriotism, morality and religion. It swallows up everything else and enlists the sympathies & energies of the people to the exclusion of almost everything besides.” (January 29, 1844)

By the outbreak of the Civil War, Jane and Harriet are young adults, and Harriet gets involved with the war effort. She writes to her stepmother, Abigail Hawes:

“I was in sewing for the Soldiers yesterday. I made a Havelock. I guess there were over thirty ladies there sewing. The Bardstown ladies are making clothing for Capt. S[?]’s company. They leave on next Monday. [...] I went in early last Monday morning to see our company off. The flag was presented by Mr Beaumin to Capt. Nesbit. Then Mrs Thompson & Luther Martin presented Testaments & ‘Prayer Books’ (some of Mrs. McAfee’s work) they then marched up to the depot followed by men women & children. Such a sight I never witnessed. Some of the soldiers (large men) cried like children – bade goodbye to every body – men that I never saw before came up & bade me goodbye & then turned their heads away to hide the tears. [...] But to go back to our Sewing Society you ask ‘will they really do anything’? I tell you they really have done something. Made seventy five shirts (& intend making so many more) of blue & red flannel, & forty five or fifty Havelocks, about thirty five towels, eighty pin cushions (or needle books). Then when the company went away the ladies supplied them with either a blanket or a comfort apiece [...] The ladies also intend making bandages or something to fasten tight round their stomachs to keep them from taking dysentery so readily.” (June 4, 1861)

Harriet notes that Abigail doesn’t “seem to be much disturbed about the war” (May 20), though she requests that although “We all admire your patriotism [...] be sure & dont send us an envelope with ‘Death to Traitors’ on it” (June 4).

Other letters from Harriet and Jane discuss school, family, and especially health; a number of deadly diseases were rampant throughout the century, and many letters read as litanies of dead and dying friends and family. The CDVs from this era, mainly taken in studios in Blairsville, seem to be mostly family friends or employees at the Female Seminary; many of the subjects are identified verso.

The family’s letters in the twentieth century are similar, though with less sickness and death, and from more dispersed locations in the US—seemingly few family members remained in Pennsylvania.

One particularly interesting thread is Nancy Weeks’ correspondence with several Europeans immediately after World War II. One is Benjamin Molnar, a Hungarian living in Munich and in the process of emigrating to the US. Molnar describes himself, and continental Europeans generally, as “prejudiced [and] very nationalistic”, and explains that he would prefer to live in the American midwest or west as the “types of people” on the east coast “are rather unamerican looking” (July 14, 1949). He ends up in California, and complains to Weeks that:

“Everybody here seems to be violently pro-negro and pro-Jewish. Jews and negroes are all right I suppose and I have nothing against them but is it a sin for a white man to prefer to live among his own kind?” (December 27, 1949)

On the other end of the spectrum are the Bjelkes, a Norwegian family who write a number of times to Nancy. They describe the Nazi invasion:

“Reidar drove me and the children (7 & 2 years) up in the country, the first day, thinking we would be safe there, he had to leave right away to do his duty of course and we were left alone. Not many days later we were in the middle of the whole war, shooting and bombing all around, then the middle of the nite we had to flee, out in the snow, two children and no place to go, at last I could no more and together with some others we broke the window of a little mountain home and crawled thru, finding the house empty. [...] But the peace was short, not long after some soldiers came and said we must off as the germans would soon be there. Well out in the deep snow again and we struggle thru and at last came to a little mountain farm where we were allowed to stay. But they had little food and for four weeks we starved [...] At last Reidar found us and we wandered our way towards home [...] to Bygdo. Mother had been there all the time and everything had been fine there.” (October 10, 1945)

They also tell Weeks about Oslo during the war, and their experience of the occupation:

“We demonstrated our hate as far as we dared to – by not sitting beside any Germans for example on the car, it went so far that they put up a ticket saying ‘no seat must stay vacant, or we would be arrested.’ The result was that we just stood all the time, then a new ticket came up, we were not aloud to stand. Well I had to jump off the car several times in order not to seat myself beside a uniform. Then they started taking our red caps & scarfs – we, used them as a demonstration you see, & they not only took them off us, but kept them. They even took our red jackets from us if we dared wear them on the street, & so many dared! On our Kings last birthday, during the war, several hundred were arrested because they wore flowers in their buttonholes–, Oh the Germans & Naszi were so childish.” (May 11, 1945)

They also describe the difficulties of postwar life, including the dangers of unexploded ordnance left around the area, which stop the ferries from running to Oslo and injure the family’s young son Per.

Overall, the archive is notable for its breadth, spanning at least four generations of a family and many historical eras and events.