Collection of Letters Sent by Steamboat to Boston Merchants Silas Pierce & Co., 1840–1849, Discussing the Citrus Trade, Sicilian Merchants, Sales and a Check that “may remove all scruples”

- Eight letters

- New York City , 1849

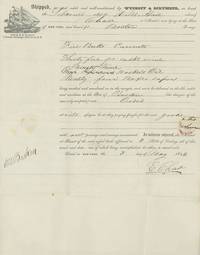

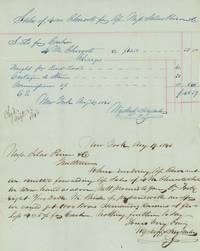

New York City, 1849. Eight letters. Overall excellent.. A small collection of letters to Boston-based grocers Silas Pierce & Co., sent from New York by steamboat, with notes on covers or stamps reading “Boat Mail” or “Steam Boat Mail”. Five of the letters are from Wyckoff & Scrymser, which was likely owned by a member or members of the prominent New York Wyckoff family (the Scrymser surname first appears in the Wyckoff family history in 1841[1]). Wyckoff & Scrimser discuss sweet and red wine prices, “opperations in Trent” (likely Trento, Italy), delayed shipments, and issues with products; for instance:

“The Harmony has not yet made her appearance neither the Aselia, the non arrival of the latter is very perplexing, but we see no remedy for it. [...] Annexed please find the sales of the [?] Raisins, amount Nett proceeds to your Co Nine Thousand One Hundred Seventy Four 06/100 Dollars, which we hope may be found correct and satisfactory. There were a number of the parcels that were sold from the wharf but rejected, which we were obliged to [?] and store, that the objections might not be known &c. The half boxes [...] did not have any external appearance of damage, and could onky be known by opening. We rather congratulated ourselves, that we have got off so well with this fruit, as we had strong fears of the result.” (December 29, 1843)

Also discussing business with Italy is a letter from Wm. A Lüs on behalf of Ferd. Baller & Co. of Messina, which traded in citrus fruit:

“The principal object of my friends is to introduce their Brand favorably into your market & their efforts to do this will alone be sufficient to secure you a superior article of fruit & other Goods; [...] they are also in the position of obtaining any other Sicilian produce at the most advantageous terms while at Messina or Palermo through their agent there.” (August 30, 1849)

Demand for citrus products was high as it had been discovered late in the 18th century that citrus prevented and cured scurvy. Demand was so great, in fact, that some researchers partly credit the citrus trade with creating the Sicilian mafia.[2]

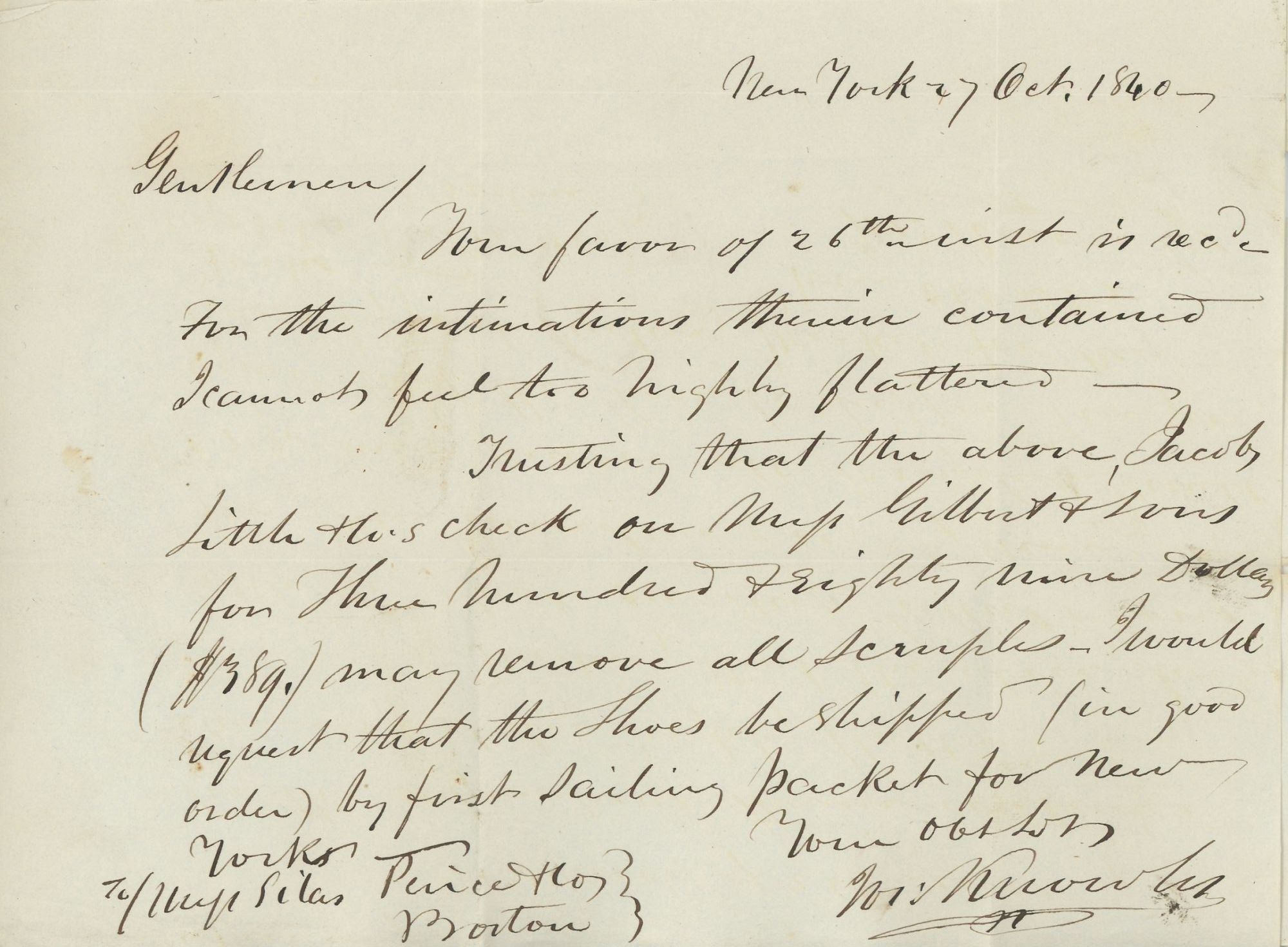

A letter from the Bank of Commerce in New York discusses credit, and lastly, Joseph Knowles, possibly of the Massachusetts-based Thomas Knowles & Company, sends an intriguing note:

“Your favor of the 26th inst is rec’d For the intimations therein contained I cannot feel too highly flattered — Trusting that the above, Jacob Little + Co’s check on Messrs Gilbert & Sons for Three hundred + eighty nine dollars ($389) may remove all scruples – I would request that the shoes be shipped (in good order) by first sailing packet for New York”. (October 27, 1840)

This is plausibly related to the investor and stock speculator Jacob Little (1794–1865), known for his short-selling tactics and generally considered, as Knowles suggests, unscrupulous.[3]

Of interest to researchers of mercantile history in the northeast and steamboat mail.

[1] Mr. and Mrs. M. B. Streeter (Eds.), The Wyckoff Family in America: A Genealogy (The Tuttle Company, 1934): 310.

[2] Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi, and Ola Olsson, “Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The Market for Lemons,” The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 4 (December 2017): 1083–1115.

[3] “The Convertible Bonds: How Jacob Little Manipulated Matters Years Ago”, The New York Times, February 23, 1882.

“The Harmony has not yet made her appearance neither the Aselia, the non arrival of the latter is very perplexing, but we see no remedy for it. [...] Annexed please find the sales of the [?] Raisins, amount Nett proceeds to your Co Nine Thousand One Hundred Seventy Four 06/100 Dollars, which we hope may be found correct and satisfactory. There were a number of the parcels that were sold from the wharf but rejected, which we were obliged to [?] and store, that the objections might not be known &c. The half boxes [...] did not have any external appearance of damage, and could onky be known by opening. We rather congratulated ourselves, that we have got off so well with this fruit, as we had strong fears of the result.” (December 29, 1843)

Also discussing business with Italy is a letter from Wm. A Lüs on behalf of Ferd. Baller & Co. of Messina, which traded in citrus fruit:

“The principal object of my friends is to introduce their Brand favorably into your market & their efforts to do this will alone be sufficient to secure you a superior article of fruit & other Goods; [...] they are also in the position of obtaining any other Sicilian produce at the most advantageous terms while at Messina or Palermo through their agent there.” (August 30, 1849)

Demand for citrus products was high as it had been discovered late in the 18th century that citrus prevented and cured scurvy. Demand was so great, in fact, that some researchers partly credit the citrus trade with creating the Sicilian mafia.[2]

A letter from the Bank of Commerce in New York discusses credit, and lastly, Joseph Knowles, possibly of the Massachusetts-based Thomas Knowles & Company, sends an intriguing note:

“Your favor of the 26th inst is rec’d For the intimations therein contained I cannot feel too highly flattered — Trusting that the above, Jacob Little + Co’s check on Messrs Gilbert & Sons for Three hundred + eighty nine dollars ($389) may remove all scruples – I would request that the shoes be shipped (in good order) by first sailing packet for New York”. (October 27, 1840)

This is plausibly related to the investor and stock speculator Jacob Little (1794–1865), known for his short-selling tactics and generally considered, as Knowles suggests, unscrupulous.[3]

Of interest to researchers of mercantile history in the northeast and steamboat mail.

[1] Mr. and Mrs. M. B. Streeter (Eds.), The Wyckoff Family in America: A Genealogy (The Tuttle Company, 1934): 310.

[2] Arcangelo Dimico, Alessia Isopi, and Ola Olsson, “Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The Market for Lemons,” The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 4 (December 2017): 1083–1115.

[3] “The Convertible Bonds: How Jacob Little Manipulated Matters Years Ago”, The New York Times, February 23, 1882.